FÜRTH, GERMANY — There are tragic ironies in life. And then there is the life of Henry Kissinger.

In 1938, as a teenager, he was forced to flee his hometown in Fürth, southeastern Germany. It was his mother, Paula Kissinger, who foresaw that the Nazi Party's antisemitic measures would only grow more dangerous and organized the family's escape to the United States. At least 13 close relatives would die in the Holocaust.

Expelled from the world he had always known simply because he was Jewish, Henry Kissinger started a new life in the U.S. that would lead him to the highest echelons of power.

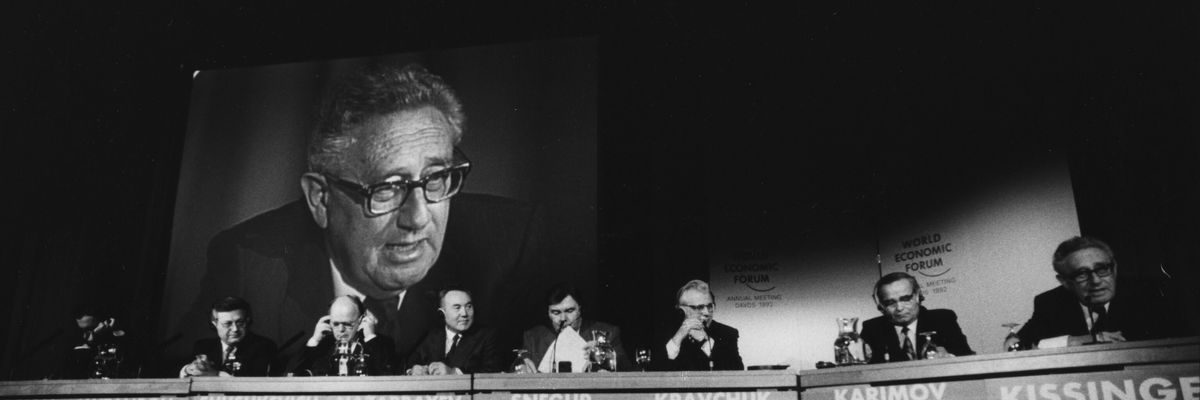

In his role as U.S. national security adviser (1969-1975) and secretary of state (1973-1977), Kissinger played a decisive role in the expansion of the Vietnam War to Cambodia and Laos and the overthrow of democratically elected leaders such as Salvador Allende in Chile. This, however, did not preclude Kissinger from receiving honorary citizenship on his return to Fürth in 1998. The man who had been the victim of a deadly hatred that would probably have ended his life had he stayed in Germany was now, six decades later, and despite his responsibility for war crimes, a role model in Fürth.

During his last visit to Fürth in May 2023 to celebrate his 100th birthday, Kissinger was feted by Frank-Walter Steinmeier, Germany’s president, and Markus Söder, the minister president of Bavaria, the federal state where Fürth is located. In a video message, Steinmeier addressed Kissinger to tell him that, "this very special mixture of scholarship and political reason, which you embody in person, is unparalleled."

In his visit to Fürth, Kissinger inaugurated the exhibition "Henry – World Influencer No. 1: The History of the Family Kissinger from Fürth." The exhibition is located in the Ludwig Erhard Zentrum, dedicated to the man who was chancellor of West Germany from 1963 to 1966 and, like Kissinger, a native of Fürth.

It would have been unreasonable to expect an exhibition inaugurated by Kissinger himself to shed much light on the darkest chapters of the statesman's life. Moreover, the biggest part of the exhibition is dedicated to the Kissinger family history, not to Henry Kissinger's political trajectory.

Still, the approach to Kissinger's years in power can only be defined as hagiographic. In one of the panels, for instance, we read that, in his role as Nixon’s national security advisor, Kissinger "aimed to end the Vietnam War and free America from foreign policy isolation. While the war seemed to be escalating with the bombardment of Cambodia, Kissinger was conducting top secret peace negotiations."

The expansion of the war to Cambodia is presented in a passive voice as if it had nothing to do with Kissinger. Facts, however, are stubborn. A Pentagon report released in 1973 confirmed that the close to 4,000 bombing raids against Cambodia in 1969 and 1970 were directly approved by the National Security Council headed by Kissinger. Between 1969 and 1973, the U.S. dropped thrice as many munitions over Cambodia — despite not being at war with the country — as it did in Japan during World War II. Leaving aside the bombardment of Laos and Vietnam, the air campaign over Cambodia resulted in the deaths of 50,000 civilians according to Kissinger’s own estimates, and over 150,000 according to independent studies.

As for Kissinger's role in ending official U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War by negotiating the 1973 Paris Peace Accords, he won a Nobel Peace Prize for it. It was another tragic irony in Kissinger's life, considering that he helped future president Richard Nixon in his sabotage of Lyndon B. Johnson's 1968 peace initiative to end the war in Vietnam. Nixon was worried that successful peace talks would lead to his defeat in the 1968 presidential race against Hubert Humphrey, the Democratic candidate and Johnson’s vice president. Therefore, and as documented by hand-written notes, Nixon ordered H. R. Haldeman, his closest aide (later to become Nixon’s White House chief of staff), to "monkey wrench" the peace talks. Kissinger proved instrumental in achieving this.

In his 2001 book "The Trial Against Henry Kissinger," Christopher Hitchens shed light on Kissinger's role. Kissinger, an unofficial consultant to the American delegation negotiating an end to the Vietnam War in Paris in 1968, became "a source of hints and tips and early warnings of official intentions" for the Nixon campaign, according to Hitchens.

Kissinger informed Nixon that Johnson was considering suspending the bombing of North Vietnam to facilitate the negotiations in Paris. Armed with these secret details, the Nixon campaign contacted the South Vietnamese government through intermediaries and promised it a better deal if Nixon won the election. Once Johnson actually suspended the bombing, South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu pulled out of the peace talks.

The exhibition dedicated to Kissinger in his hometown of Fürth, as well as the guided tour of the exhibition, stress the image of the statesman as the paradigmatic practitioner of Realpolitik. Thus, we read that Kissinger knew more than anyone else that “all states have interests, but they are rarely identical." Kissinger's role in the opening of diplomatic relations with Communist China has weighed heavily in the arguments of those who see Kissinger as mainly concerned with national interests.

Similarly, Kissinger’s scholarship, such as his 1994 book “Diplomacy,” displays a very clear interest in the balance of power. But there are reasons to believe that Kissinger, who has often been presented to us as the paradigmatic realist, was equally influenced by ideological considerations in many of his actions.

Take, for instance, the overthrow of Chilean President Salvador Allende in 1973. This is the only slightly critical reference to Kissinger's political trajectory that can be found in the exhibition in Fürth. In a picture, Kissinger is seen smiling while shaking hands with Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet, who took power after Allende killed himself during the army’s assault against the presidential palace.

Five days after the coup, in a conversation with Nixon, Kissinger said, "We didn't do it. I mean we helped them." This modesty was not justified. In October 1970, when Allende had already won the presidential elections but had still not been confirmed as president by the Chilean Congress, Kissinger met with the CIA’s deputy director of plans, who subsequently transmitted to the CIA station in Chile that "it is firm and continuing policy that Allende be overthrown by a coup."

Chile has the largest copper reserves in the world. After they were nationalized in 1971, the Allende government decided not to pay compensation to the U.S. companies that owned them. This enraged the Nixon administration but was hardly a threat to U.S. national security. The U.S. policy to overthrow Allende had little to do with Realpolitik. Ideology helps explain it far better.

Jorge Heine, a Research Professor at Boston University, writes that "what made Kissinger take such deadly aim at Allende was his new political model, a "peaceful road to socialism." If the Chilean model was replicated elsewhere, the U.S. narrative of political freedom being possible only in a free-market system would have been in trouble.

After Kissinger's death, political analysts all over the world sought to understand why the statesman generated such great fascination in both admirers and detractors. Part of the explanation is that, through Kissinger's biography, one can understand many of the key events that shaped the last 100 years.

He was there when fascism rose in Europe, fought Nazi Germany in the Second World War, and held power during the height of the Cold War. He remained a sought-after author, consultant, and commentator in the following decades, exerting influence on current discussions, such as the rise of China.

If one had to reach an assessment of Kissinger’s political life based only on the exhibition devoted to him in Fürth, one could be forgiven to think that his trajectory was exemplary. This, to put it gently, would be a very mistaken assumption.