This is one perspective in a Responsible Statecraft ‘debate’ over the value of federal aid for ‘soft power’ programs, including regional studies, think tanks, USAID, and academic exchanges. See a counterpoint by Christopher Mott, here.

Since taking office, the Trump administration has made clear it seeks to increase attention to what Secretary of State Marco Rubio has called an “Americas First” foreign policy.

But by eliminating research and educational funding for regional and international studies, the administration will find it more difficult to develop a long-term effective approach to hemispheric affairs.

The assault on expertise

Trump’s efforts to reshape the federal government will have profound implications for U.S. foreign policy. While the impact of the elimination of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) on U.S. soft power has been discussed extensively, less ink has been spilled on the administration’s efforts to eliminate various research organizations and units within the U.S. government.

In terms of international affairs, these have included attempts to shutter the U.S. Institute for Peace and the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars as well as the announcement that the Department of Defense will no longer fund social science research.

Funding for these think tanks and broader social science research has served as an important tool for assessing the impact of U.S. foreign policy and identifying policy options. By seeking to eliminate these entities, the Trump administration runs the risk not only of further undermining U.S. soft power, but also of limiting the administration’s own understanding of what is happening as a result of its policies — resulting in negative outcomes in the longer term.

Gutting the next generation of expertise

In addition to cutting funding and dismantling organizations that provide policy-relevant research and expertise, the administration is eliminating various programs that generate future experts in international and government affairs.

One clear way that this is happening has been the suspension of Fulbright Fellowship funding that provides both research and teaching grants to students and faculty to study abroad. Likewise, the Trump administration has canceled the Presidential Management Fellowship (PMF) — a program designed to bring top recent graduates into the federal service. The administration’s efforts to dismantle the Department of Education could have even longer-term implications for developing future foreign policy leaders and analysts.

At the height of the Cold War, the U.S. government realized that it needed to develop a cadre of experts who could provide linguistic support and socio-political expertise that could aid their understanding of foreign countries. To ensure that experts were available, the government funded area studies at universities across the country as part of the Defense Education Act of 1958 and the Higher Education Act of 1965. The funding for area studies is now known as Title VI.

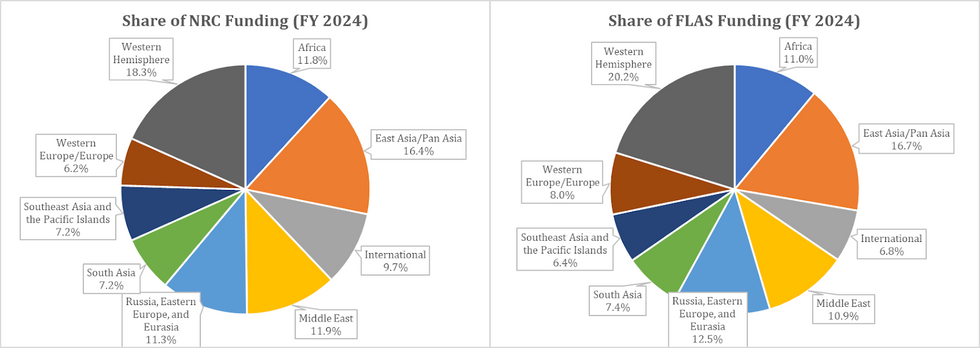

Title VI funding is used to promote education through National Resource Centers (NRCs) and Foreign Language and Area Studies (FLAS) fellowships in nine regional groups—1) Africa, 2) East Asia/ Pan Asia, 3) International, 4) Middle East, 5) Russia, Eastern Europe, and Eurasia, 6) South Asia, 7) Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands, 8) Western Europe/Europe, and 9) Western Hemisphere.

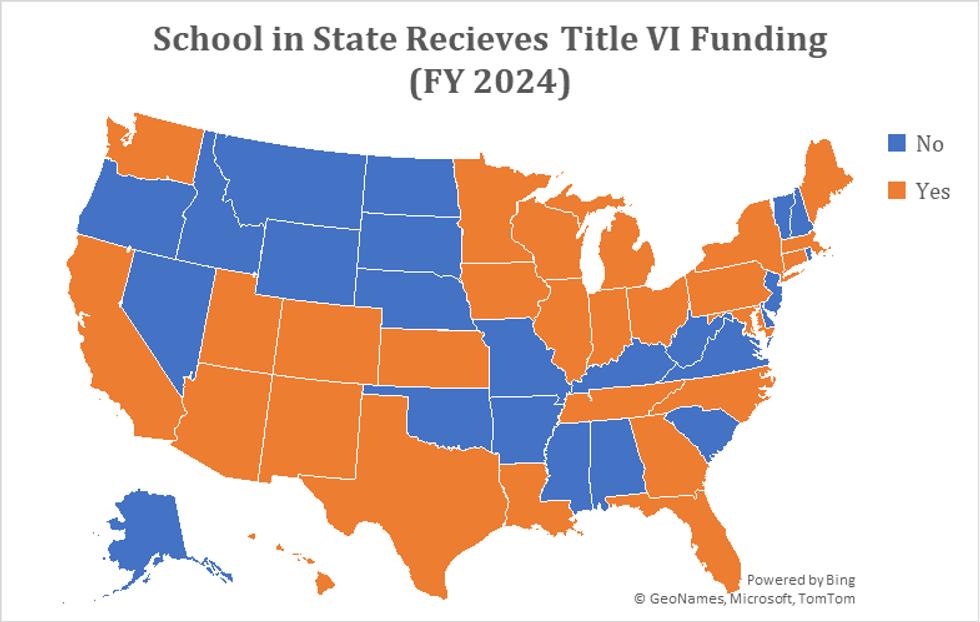

Recipient universities benefit from these programs with at least one school in 27 states and the District of Columbia receiving some form of Title VI funding for one or more regions. Notably, Title VI funding has grown in recent years with funding for NRCs growing from $22.7 million in fiscal year 2019 to $29.3 million in 2024. Many of these programs also funded outreach offices that coordinated with local communities and school districts to promote greater interest in and understanding of foreign affairs in the general public.

Source: Author’s rendering based on data from the Department of Education.

As part of its efforts to dismantle the Department of Education, the administration has effectively dissolved the Office of International and Foreign Language Education — the entity responsible for Title VI funding — and this funding is reportedly under review.

While some have argued that cutting these programs should be considered within the broader context of the Trump administration’s efforts to take on “woke” education, the original national security implications for developing Title VI remain. In addition to limiting funding for current expertise on various world regions, cutting funding for area studies runs the risk of eliminating future expertise in these areas — posing a challenge into the future when different sets of experts may be needed to help the country navigate an increasingly multipolar world.

Building support to put the Americas first

While cutting funding for these programs will have implications for all areas of U.S. foreign policy, these cuts come at a time when the Trump administration — and Secretary of State Marco Rubio, in particular — seek to realign national interests to focus more on issues in the Western Hemisphere.

The shift toward focusing on the Americas is critical given the traditional “benign neglect” of U.S. foreign policy toward the region. While the Trump administration is clearly focused on the region and has a senior team staffed with Latin Americanists, reorienting U.S. foreign policy will require deepening the bench not only among junior staff but also bolstering public interest in Latin American and the Caribbean relative to other regional hotspots.

Title VI funding was already playing an important role in increasing interest in the Western Hemisphere. Of the nine geographic regions targeted by Title VI, funding for the Western Hemisphere, which includes Canada, was the most, accounting for 18.3% of total funding for NRCs and 20.2% of FLAS funding.

This funding would have increased the number of course offerings of Latin American and Caribbean topics in universities—creating the opportunities for students to become more interested and involved in regional issues. These students go on to develop regional expertise with a portion of them entering the federal government or providing independent analyses that can allow for the development of better foreign policies.

While the impact will not be felt immediately, it will hamper future regional expertise within the U.S. government.

Source: Author’s rendering based on data from the Department of Education.

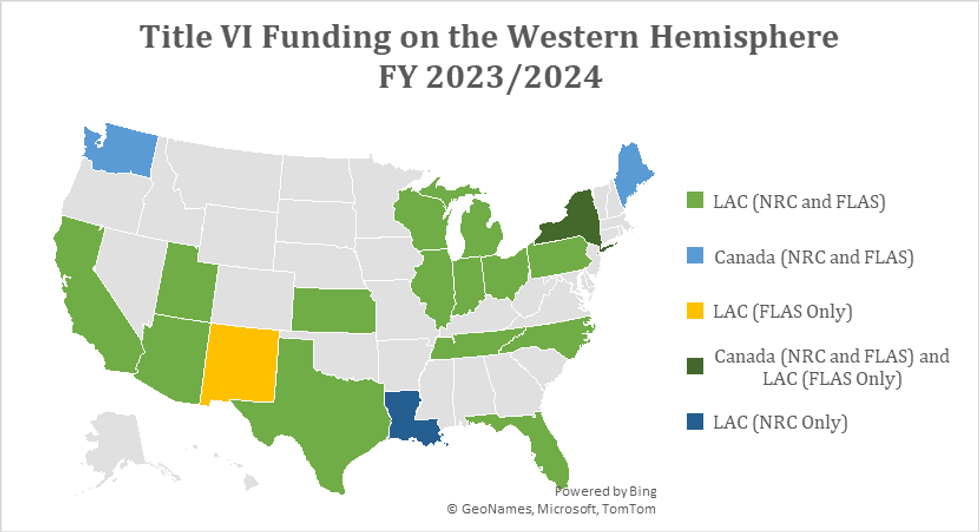

At the same time, decreasing funding for education on regional affairs will make Rubio’s efforts to shift the focus of U.S. foreign policy more challenging. While the U.S. general public is often ambivalent on most foreign policy issues, areas where they see a shared destiny or identity are spaces where the United States is more likely to engage. The various NRCs play a critical role in building public interest in the Western Hemisphere — from hosting events to helping develop curricula to incorporate Latin American and Caribbean themes into K-12 education.

While engaging the public to boost interest in the Western Hemisphere must go beyond the work done by NRCs, these institutions provide a necessary mechanism for engaging the public outside the DC-New York Corridor. It is also worth noting that the vast majority of Title VI funding on the Western Hemisphere was focused outside the traditional hubs of U.S. foreign policy making (with only 1 of the 22 FLAS rewards — and none of the NRC funding — devoted to a program in New York City [shared by Columbia University and New York University] and none to the DC schools).

Source: Author’s rendering based on data from the Department of Education.

Conclusion

The Trump administration’s efforts to shift the focus of U.S. foreign policy while crippling area studies at universities and dismantling government research entities will have profound consequences for its ability to improve regional relations. Funding for research and scholarship on Latin America, the Caribbean, and Canada is critical to developing future cadres of foreign policy professionals essential to ensuring long-lasting foreign policy shifts while also maintaining public interest in a region that is often ignored in favor of other geopolitical hotspots.

If the Trump administration wants an “Americas First” foreign policy to last, it needs to recognize the risks of its actions on regional affairs and expertise.