“Did I help fix an election? Yes.”

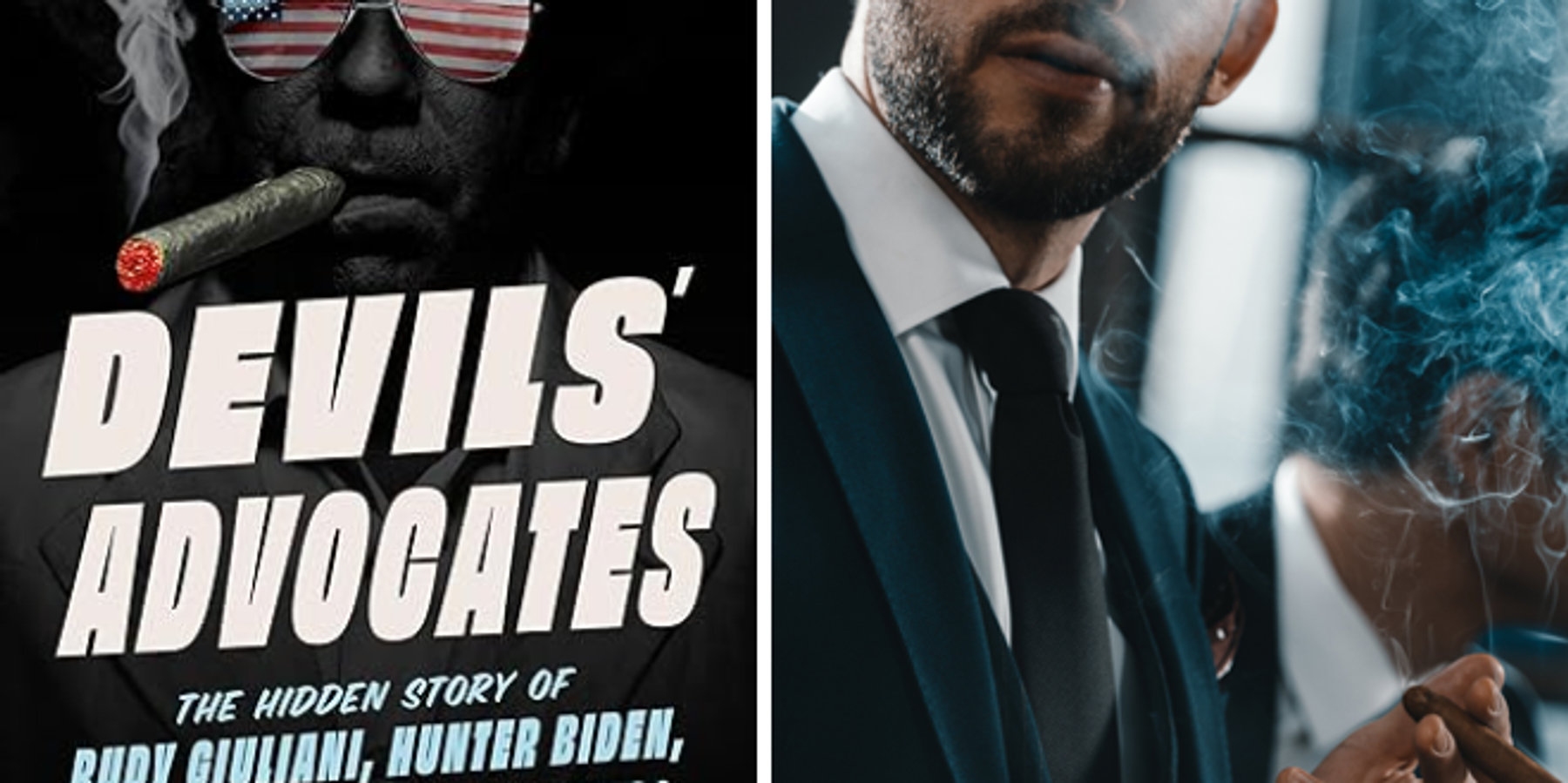

Or so claims foreign lobbyist Robert Stryk in “Devils’ Advocates: The Hidden Story of Rudy Giuliani, Hunter Biden, and the Washington Insiders on the Payrolls of Corrupt Foreign Interests,” a new book by New York Times reporter Kenneth Vogel about the inner workings of American lobbyists working for foreign governments.

In Stryk’s telling, he paved the way for the first Trump administration to accept a power sharing agreement for then-DRC President Joseph Kabila, netting $1.8 million in the meantime from an Israeli surveillance company with a vested interest in maintaining access to Congolese mines. Kabila, then facing U.S. threats of sanctions and asset seizure, would retain control over parliament and key posts and assume the title of “senator-for-life” in exchange for handing over the presidency to opposition candidate Felix Tshisekedi.

While Vogel’s book is chock-full of original reporting about familiar faces in U.S. politics like Rudy Giuliani and Hunter Biden, its little-known lobbyist Stryk who steals the show. Stryk fashions himself as a foreign lobbyist cowboy, travelling the world over to meet with foreign clients and push U.S. policy in their favor (for a price) while donning boots, jeans, and a v-neck shirt.

On the surface, Stryk appears to be a natural in the art of foreign influence. Almost overnight, he went from tending his Oregon vineyard to securing over $19 million in lobbying fees during the first Trump administration. And oftentimes, Stryk convincingly delivered for his clients, to the point where the number two official at New Zealand’s embassy referred to him as her “guardian angel” after introducing embassy officials to assorted figures in Trump world.

Naturally, Stryk found his way to authoritarian regimes in Somalia, Angola, Bahrain and Saudi Arabia. A Quincy Institute analysis of foreign lobbying from 2022-23 found that 65% of the most active foreign government lobbies were rated “Not Free” by Freedom House. Authoritarian governments often hire lobbyists like Stryk to paper over their human rights abuses, get rivals put on sanctions lists, or to smooth over arms deals.

Stryk is no exception. He took credit for blocking a bill introduced by U.S. Senator Rand Paul (R-Ky.) which would have blocked a sale of $300 million worth of army rockets and missiles to Bahrain, a key supporter of the Saudi-led military intervention in Yemen. Paul, a leading critic of the military intervention, “went apeshit” on one of Stryk’s employees for representing Saudi Arabia and Bahrain, according to the employee.

On another occasion, he claimed he successfully blocked a U.S. effort to impose sanctions on Angolan billionaire Isabel dos Santos, who was under investigation for siphoning off $1 billion during her father’s presidency. Stryk takes pride in this kind of work — what he calls the “shitbag world.”

What makes Vogel’s book so compelling is that Stryk is also a master in the art of illusion of influence. High-end political watering holes serve as staging grounds for Stryk to flaunt access in front of prospective clients. To this end, Georgetown restaurant Café Milano features almost as prominently as other side characters in Vogel’s Devils’ Advocates.

Case in point being Stryk’s work for the DRC. Stryk may embellish, telling the Congolese that the National Security Council promised to avoid prosecution or seizure of Kabila’s assets if there was a peaceful transfer of power, which the Trump administration denied. But his firm, Stryk Global Diplomacy, did meet with National Security Council officials to discuss the possibility of Kabila avoiding sanctions. And Stryk did organize an event on the rooftop of the Hay-Adams hotel with Congolese officials and Trump world figures (including a paid appearance from Rudy Giuliani) to further ties between the two.

But did Stryk “fix an election” as he claims?

Prospective clients certainly thought so. Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro tried to hire Stryk to get the U.S. to drop sanctions in exchange for opening the economy. “I did it for Kabila. I will do it for Maduro,” said Stryk, who met with Maduro in Miraflores, Venezuela’s presidential palace. When Stryk and his partners disclosed their work for Venezuela, the furious backlash from anti-Maduro hardliners caused him to terminate his contract. There are limitations, even for the “shitbag world.”

It’s oftentimes an impossible question when focusing on an individual outcome; lobbyists have every incentive to play up their influence to clients, which sometimes means perceptions matter more than outcomes. Stryk would frequently take clients to the Grand Havana Room lounge just because he knew Rudy Giuliani would be there. “The very fact that I could sit with him and ‘Hey Robert, have a cigar!” — that gave the client the belief that I was close enough to the most powerful person outside of the president of the United States,” said Stryk.

Meanwhile, the U.S. government has every incentive to deny that outsiders like Stryk play any role in influencing policy. As Vogel writes, "Such ambiguity and confusion about influence and deliverables is a defining feature of foreign lobbying, and it serves all involved.”

The New York Times review of Vogel’s book, written by Rutgers University professor David Greenberg, seems to take this ambiguity as a “gotcha.” Greenberg writes that “Vogel never establishes that American foreign policy is, as he asserts at the outset, ‘for sale.’ And Vogel never fully reckons with the extent to which decision makers take into account such imperatives as American economic interests, security concerns, regional balances of power and public opinion.”

Of course those considerations matter to the U.S. government, but foreign policy is unusually rife for lobbying compared to other policy arenas. Vogel writes that “with a few notable exceptions — military support for Israel or opposition to the Cuban socialist regime — foreign policy causes mostly lack domestic constituencies.” This makes it far easier for foreign governments to hire lobbyists to swoop in and swoon key government officials.

And whether his influence was real, perceived, or somewhere in the middle, Stryk always got paid. On one occasion, Stryk took in nearly $6 million for a contract with Saudi Crown Prince Muhammad bin Nayef (MBN) in an attempt to undermine then-Deputy Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS), only for it to be terminated weeks later.

Devils’ Advocates walks the reader through how the foreign lobbying world really works — the lobbyists, the think tanks, the key Congressional targets, the foreign governments. While it’s easy to get lost in Stryk’s stories about driving jaguars in Bahrain or facing gunfire in Mogadishu, it shouldn’t be lost on readers that the “shitbag world” can have real consequences for real people.

Vogel makes this point explicit in the end, concluding that foreign lobbying is a “winning formula for the lobbyists and their deep-pocked clients seeking to protect their often ill-gotten fortunes, but not for regular Americans whose government is spending their tax dollars on policy that doesn’t reflect their interests, nor for the regular people in faraway lands who are oppressed or ill-served by that policy.”