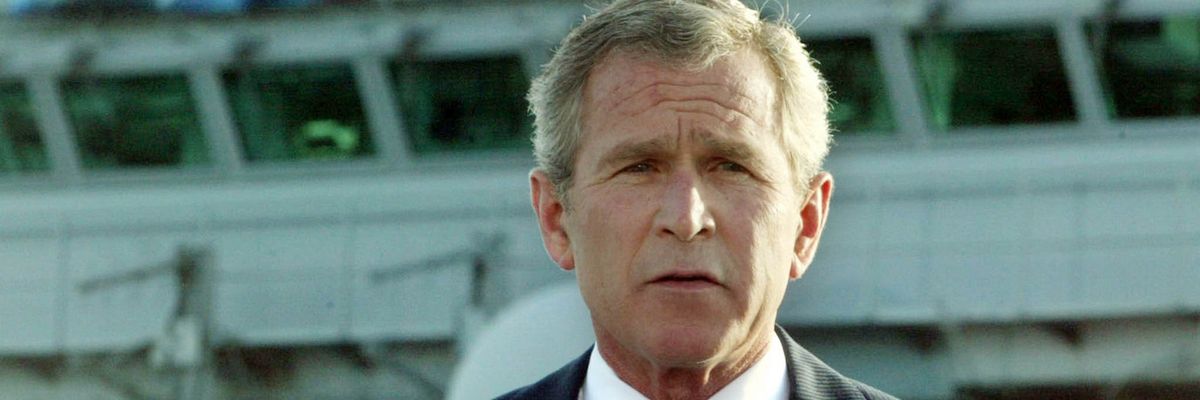

Twenty years ago on May 1, President George W. Bush took to the deck of the U.S.S. Abraham Lincoln to announce that “major combat operations in Iraq have ended.”

In front of a now-infamous banner on the carrier’s bridge reading “Mission Accomplished,” President Bush declared victory before the United States and Iraq had yet to experience the fullest extent of that war, which began three months earlier in March 2003.

Sixty years before Bush’s speech, Prime Minister Winston Churchill offered a more measured assessment of the fruits of temporary victory.

After the 1942 Allied success at the Second Battle of El-Alamein, Churchill soberly prepared his country for the long, remaining struggle ahead to defeat the Nazi war machine. “Now is not the end,” he remarked, “It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.” Had Americans known the chaos that was set to unfold over the next two decades in Iraq, they may have found Churchill’s adage more fitting.

In fairness, President Bush was right to congratulate the soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Marines in Operation Iraqi Freedom for executing a stunningly successful conventional military campaign that cut across 350 miles to Baghdad in less than a month. But we cannot let appreciation of tactical and operational skill blind us to the geopolitical hubris of a war that brought strategic disaster to the United States and indelibly altered the lives of millions of Iraqis.

In his address, President Bush expressed an unfounded post-Cold War optimism about America’s ability to remake the world in its image by force rather than by example. Arguing that advances in military technology allowed regime change wars to be more achievable while minimizing civilian casualties, Bush stated “it is a great moral advance when the guilty have far more to fear from war than the innocent.” The sad reality is that, in 2003 alone — the year of Bush’s speech — an estimated 12,000 Iraqi civilians were killed in the conflict.

It is hard to square the president’s hopes for a moral outcome in Iraq with the invasion’s most brutal legacy — the tens of thousands of innocent Iraqis killed every year for most of the rest of the 2000s. By creating a power vacuum, the invasion allowed opportunists to inflame latent sectarian divisions, spiraling the country into savage confessional and tribal conflict. To date, an estimated 187,000 to 210,000 Iraqi civilians died in the violence of the Iraq War. Much of this total is also due to the rise of ISIS in the 2010s, a group formed from Sunni insurgent factions that took root following the invasion.

The legacy of Wilsonian idealism can make it difficult for U.S. decisionmakers to accept that foreign policy necessarily involves sober tradeoffs more often than lopsided victories. Saddam Hussein directed a brutal regime, and Iraqis deserved a better future. But it has never been enough to justify a foreign policy strategy through a confident claim of its moral superiority when its implementation unleashes such monstrously immoral outcomes.

At the time of the president’s speech, Americans had yet to pay the main costs of the Iraq War. The years immediately following “Mission Accomplished” were the deadliest in the conflict, which has left 4,500 U.S. troops killed and over 32,000 wounded. American taxpayers can expect to pay nearly $3 trillion for the Iraq War through 2050 when factoring the costs of veterans’ care, war-related defense spending increases, and additional interest on the national debt.

On a strategic level, President Bush was even more pollyannaish. He declared that, in deposing Saddam, the U.S. had “removed an ally of al-Qaeda” and prevented terrorist networks from “gain[ing] weapons of mass destruction from the Iraqi regime.” These claims reinforced since-disproven narratives that there was a connection between Saddam Hussein and Osama bin Laden to begin with, or that the Iraqi government had weapons of mass destruction.

The key results of the invasion were two-fold: it empowered Iran to expand its influence in Iraq and across the Middle East by removing a check, and it aided our great power competitors, Russia and China, by distracting us in counterinsurgency operations for decades, delaying modernization programs, and wearing out our all-volunteer force and its strategic assets — such as the B-1 bomber fleet — from overuse.

How can we turn the page on this failed legacy? First and foremost, it is past time for U.S. forces to exit Iraq. We have long-since defeated ISIS’ territorial caliphate, leaving no clearly achievable mission left for U.S. forces. Further, the ability of the U.S. and its allies to launch strikes against ISIS leaders is well-proven. Remaining in Iraq only makes U.S. forces subject to ongoing attack from Iranian-backed militias, which have documented ties to the very Iraqi security forces our troops are training and equipping. If the president is unwilling to remove U.S. troops from Iraq, Congress should consider ending funding for our continued presence there, the same method it used to help finally bring the Vietnam War to a close.

Secondly, Americans must demand that Congress take seriously its constitutional obligation to decide questions of war and peace to avoid foolishly sending our men and women in uniform rushing headlong into conflict, or, worse, keeping them in harm’s way for decades with no clear objectives. The 2002 Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF) Against Iraq, which provided the legal basis for Operation Iraqi Freedom, was introduced and sent to the White House in just over a week, despite the sweeping consequences of the war.

Americans and our troops deserve greater deliberation when we are choosing a war rather than having it thrust upon us. Congress cannot be a mere rubber-stamping body for executive action.

To this day, both Iraq AUMFs, from the Gulf War and the 2003 invasion, are still active, leaving open the possibility that a president could misuse them to take us back into war in the region without securing congressional approval first. Fortunately, a repeal effort recently passed the Senate with 66 votes, and is headed to the House, which has already voted to repeal Iraq AUMFs four times. Americans should demand that their representatives finally finish the job.

Twenty years later, the “Mission Accomplished” speech is a tragic reminder of the consequences of seeing the world how we wish it could be rather than how it is. For the sacrifices our servicemembers and the Iraqi people faced in its wake, May 2003 must inspire a rededication to a foreign policy firmly rooted in American national interests that promotes our values by example rather than by the sword.