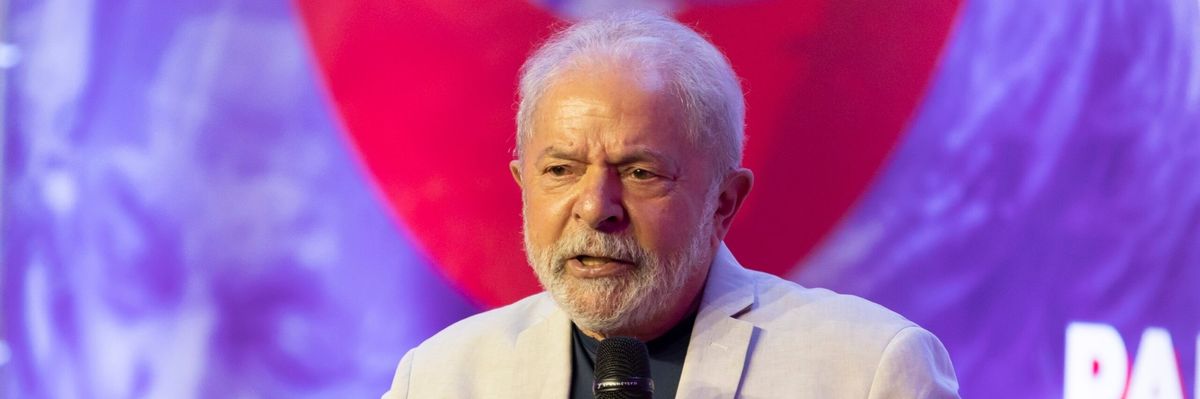

In his victory speech Sunday night, former president — and now president-elect — Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva said that the world missed Brazil as it sunk to a state of unprecedented international isolation in recent years. Lula, an impassioned orator used to speaking extemporaneously, calmly read prepared remarks that struck notes of harmony, healing, and restoration.

“Brazil is back,” he said.

Lula’s unlikely ascent to another term in office in Latin America’s largest nation represents renewed opportunities. Indeed, given the host of issues Brazil faces — including reigning in deforestation, navigating the decline of U.S. hegemony in the hemisphere, and reversing an alarming slide into deindustrialization — it is hard to imagine someone better equipped than Lula to turn the page from the far-right Jair Bolsonaro, who has governed the country since 2019.

For the Biden administration, Lula’s return to power is also fortuitous as it offers a chance to reset relations. As his first stint in office came to a close, Lula successfully ensured the election of his former chief of staff, Dilma Rousseff. Her term, however, would be rocked by widespread street demonstrations that shook the foundations of her popular support and an economic crisis driven, among other things, by fallout from the global 2008 crash. But the most visible sign of a radical shift in Brazilian politics under Rousseff was Operation Car Wash, the massive federal investigation into corruption that brought down several high-profile businessmen and politicians.

Lula himself was ensnared in the fallout of this unyielding anti-corruption crusade, leading to his imprisonment for almost 600 days. The charges against Lula have since been dropped, and, as left-wing forces had asserted all along, the judge who sentenced him was revealed to have been driven by political animus.

Now, Lula has completed the most astonishing political comeback since perhaps Nelson Mandela. Yet many on the left continue to believe that the United States played a critical role in the political turmoil that engulfed Brazil over the last decade, including Lula’s arrest. Lula himself has frequently said the U.S. Justice Department under President Barack Obama deliberately intervened in Latin America, seeking to hurt him politically because it favored the deference and promises of economic privatization made by his opponents.

There is no smoking gun that the Obama administration orchestrated events that led to his downfall, but there are lingering resentments that Lula can and should work to transcend as he has during this campaign with many of the key figures who supported Dilma’s impeachment on fragile grounds in 2016.

If Washington wants to overcome that distrust, it should welcome engagement with a new Lula administration. Doing so would help the United States reset popular conceptions in Latin America of how the United States views progressive governments in the region generally and Brazil’s hemispheric aspirations in particular. The Biden administration has already pleasantly surprised Gustavo Petro in Colombia and Gabriel Boric in Chile with its willingness to work closely on matters of mutual concern.

Lula’s winning coalition will expect the same level of respect. In fact, the Biden administration very quickly issued a statement Sunday night acknowledging Lula on his win and the president later congratulated him on Twitter.

Despite a history of democratic instability and ideological flux at the highest levels of power, Brazilian leaders have always been united in their desire for international recognition. Biden can and should bear that in mind as he opens a new era of relations with Brazil.

Brazil is also a massive country with a youthful population, bountiful resources, and technical proficiency in several key areas. Since the return of democracy in the late 1980s following two decades of military rule, successive administrations, particularly in the last 20 years, have passed social-democratic policies that have earned international acclaim.

A conditional cash-transfer program created during Lula’s first term, for example, lifted millions of poor families out of extreme poverty, and the largest public health system in any democracy is Brazil’s Sistema Único de Saúde. And yet, as Bolsonaro’s time in office demonstrated, international goodwill is a perishable asset.

Rapid U.S. recognition of Lula's win was the culmination of months-long efforts by Washington to dissuade Bolsonaro from pursuing anti-democratic means of staying in power. Indeed, as Bolsonaro spent months insinuating his country could not hold a free and fair election, the Biden administration insisted that support for a coup would not be forthcoming and that Brazil risked serious damage to its relationship with the United States in the event of anti-democratic activity from the president or the armed forces.

It is unclear how much this signaling affected decisions in Brazil, but the military brass there has consistently reiterated it would respect the outcome of the election. Given Washington’s history of support for anti-communist military dictatorships in Latin America throughout the Cold War, the Biden administration’s attitude was marked by a welcome restraint.

Lula will take office on January 1 in a world much changed since his first election 20 years ago. But he is still committed to the BRICS — the loose association of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa identified as emerging economies with harmonious interests in many respects — as a framework to counterbalance the enormous power of the United States to shape economic and political outcomes around the world.

Regional integration has also long been a priority for Lula. Instead of taking issue with this predilection, which has deep roots in Brazil’s diplomatic history, the Biden administration would do well to acknowledge Brazil’s aspirations to hemispheric leadership.

In fact, the Lula administration has the credibility and ideological flexibility to serve as a mediator for some of the most challenging diplomatic issues in the region. He is a trusted interlocutor of Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro and Nicaragua’s Daniel Ortega, both of whom he has chided even as he’s insisted on their right to sovereignty. He also has the standing to speak openly with both Havana and Washington.

Instead of bristling at Brazil’s attempts to foster diplomatic solutions in Latin America and beyond, as the Obama administration did when Lula sought a deal to limit Iran’s nuclear capabilities under then-president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, the Biden administration should recognize Lula as a serious democratic partner able to address thorny diplomatic issues from a different angle than the United States.

The same is true when it comes to the environment. Perhaps no single issue turned world leaders against Bolsonaro as much as the deforestation of the Amazon that was allowed to reach worrisome levels on his watch. Here too, the United States must recognize Brazil’s technical capabilities. In terms of policy and implementation, Brazil has demonstrated its ability to drastically reduce deforestation. Any talk of an international role in the Amazon, as French president Emmanuel Macron suggested in 2019, would be counterproductive since opposition to foreign designs on the world’s largest rainforest has been a point in common for Brazilians on the political left and right for decades.

China’s increasing presence in Latin America is also a development for which the United States should look to rely more, not less, on Brazil. A foreign policy based on restraint needs partners. Recognizing Brazil’s ability to make decisions in its own interest that don’t directly hinder U.S. interests should be the northstar of relations with Brazil.

Brazil is a major democracy with advanced technical capabilities. The United States has often acknowledged this even as, historically, it has undermined Brazil’s ability to govern itself. A new Lula administration will bring a host of challenges but also opportunities, including a fresh diplomatic start rooted in mutual respect, restraint, and cooperation.