This Sunday, October 16, marks the 20th anniversary of the law that authorized the invasion of Iraq and as the result of growing bipartisan consensus, Congress may just be on the precipice of finally repealing this decades-old war authority.

History speaks strongly to the motivation for its repeal.

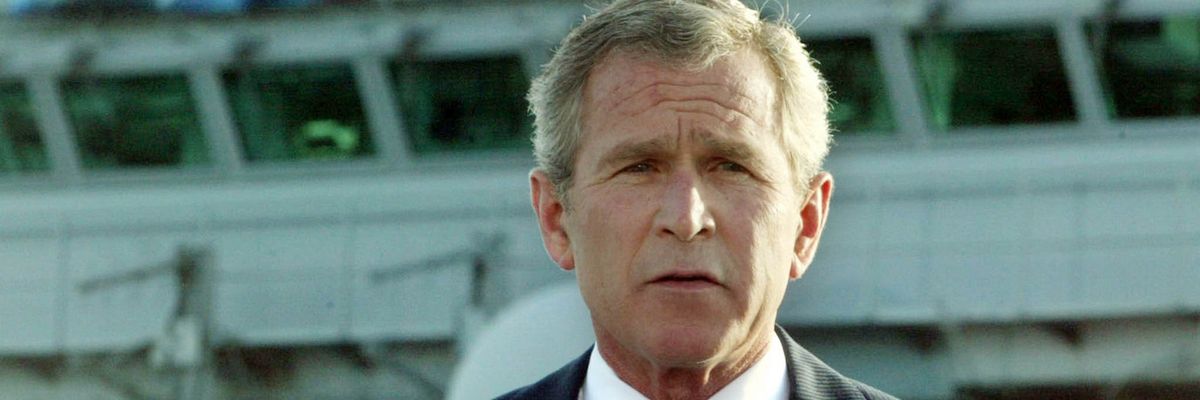

Congress passed the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq, or the Iraq AUMF, in response to a request from President George W. Bush in October 2002. Enacted 13 months after the 2001 AUMF, which was directed against those responsible for the 9/11 attacks, the Iraq AUMF was drafted for a very different purpose. Specifically, the resolution permitted the president to use armed forces as “necessary and appropriate” to “defend U.S. national security against the continuing threat posed by Iraq” and to “enforce all relevant Security Council resolutions regarding Iraq.”

The reference to such resolutions concerned the allegation that the Saddam Hussein regime was in breach of certain U.N. Security Council resolutions that prohibited the possession of weapons of mass destruction. A presidential commission concluded in 2005 that “not one bit” of the U.S. intelligence community’s assessment that the regime had begun producing nuclear, biological, or chemical weapons proved correct. Yet this false claim seems to have become a minor footnote in the historical record of the war that followed.

Saddam was quickly deposed and President Bush declared “Mission Accomplished” and an end to major combat operations on May 1, 2003. Despite this declaration, and the former Iraq leader’s execution in 2006, the fighting continued. By the time President Obama officially declared the Iraq War over and removed all U.S. troops from the country in December 2011, it was estimated that at least 126,000 Iraqi civilians had been killed, along with 4,500 U.S. servicemembers. Thirty-two thousand more troops were wounded in the war, which cost taxpayers approximately $800 billion.

With the Iraq War having been officially over for nearly 11 years, it begs the question as to why, apart from being a matter of historical interest, the law that authorized it even merits discussion. Indeed, prior to the post-9/11 era, the anniversaries of statutory force authorizations or declarations of war have been seldom observed, let alone accompanied by calls for their repeal.

That’s because, historically speaking, the repeal of such instruments hasn’t been necessary to mark a final end to their use by the executive branch. Prior administrations generally accepted that the end of a conflict rendered the statue that authorized it obsolete. This was the case even when the enemy was the same. For example, President Roosevelt never attempted to rely on the 1917 declaration of war against Germany to justify war against Hitler’s Nazi regime 24 years later. Rather, he sought a fresh authorization from the body with the constitutional power to “declare war.”

This has not been the case for the Iraq AUMF. Despite Congress’s very clear intent for the resolution, as exhibited by both its text and legislative history, successive administrations have interpreted the Iraq AUMF far beyond its original purpose.

These expanding interpretations began in 2014, when President Obama authorized the deployment of troops to Iraq to fight ISIS. While the Obama administration asserted that the 2001 AUMF provided congressional consent to this new mission, it also claimed that the Iraq AUMF offered “an alternative statutory basis on which the president may rely for military action in Iraq.”

The Obama administration would later broaden this interpretation, stating in a December 2016 report that the 2002 law also applied to operations against ISIS in Syria. In a footnote of this report, the administration asserted that the Iraq AUMF “reinforces the authority for military operations against ISIL in Iraq and, to the extent necessary to achieve these purposes, elsewhere.”

In 2018, the Trump administration went even further, claiming that the Iraq AUMF sanctioned the use of force to address both “threats to, or stemming from, Iraq.” This significantly stretched the law’s breadth, enabling its potential use to justify military action against any number of regional threats to Iraq, whether by non-state group or nation state.

Acting on this latest reading, the Trump administration invoked the Iraq AUMF to justify the targeted killing of Iranian general Qassem Soleimani in January 2020, nearly 18 years after its passage. This justification was rejected by legal scholars. Congress responded by passing a resolution directing the cessation of hostilities against Iran. This resolution, which passed with bipartisan majorities in both chambers of Congress, was ultimately vetoed by President Trump.

Over the last few years, frustration has grown among an increasingly bipartisan majority in Congress over the executive branch’s usurpation of Congress’s constitutional power to decide if, when, and against whom, the United States goes to war.

While trepidation remains concerning how to approach the post-9/11 2001 AUMF, the Iraq AUMF is an entirely different story. The executive branch has confirmed that the Iraq AUMF is not needed for any current military operations. Its repeal would begin a long-overdue process of rebalancing the constitutional division on war powers, amounting to what many call “constitutional hygiene.” It would also prevent any further abuse of the law by an enterprising executive branch that has defined it more broadly and any lawmaker could have conceived in 2002.

This year, the House adopted an amendment from Rep. Barbara Lee (D-Calif) to repeal the Iraq AUMF as part of the annual defense policy bill, the National Defense Authorization Act. Senators Tim Kaine (D-Va.) and Todd Young (R-Ind.) have filed a corresponding amendment to the Senate NDAA, which mirrors their standalone bill that currently has 51 cosponsors, including 11 Republicans. The bill cleared the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in June, 2021, by a bipartisan vote of 14-8.

Significantly, repealing the Iraq AUMF has the backing of the Biden administration. In June 2021, the Biden White House issued a Statement of Administration Policy, stating unequivocally “The Administration supports the repeal of the 2002 AUMF.”

This effort is also supported by a wide variety of organizations that reflect the bipartisan congressional support, including veterans groups the American Legion and Concerned Veterans for America, as well as September 11 Families for Peaceful Tomorrows, whose members all lost loved ones in the 9/11 attacks. The endeavor also reflects the sentiment of the American people, with more than 80 percent of the public in favor of constraining the president’s war-making powers and increasing congressional oversight on the use of force.

On this 20th anniversary of the Iraq AUMF, it is important to reflect on the costs and consequences of this law. After years of bloodshed, billions of dollars spent, and the acquiescence of its constitutional war powers, Congress finally looks set to repeal this outdated war authorization. For a war-weary public, eager for their elected representatives to re-set constitutional checks and balances, the closure of this chapter couldn’t come soon enough.