The American Secret War is not over for me, though it’s been nearly five decades since the last bombs were dropped on Laos.

Veterans like me know that war is never over when we return home. Instead, it is often the beginning of more suffering and a long, nonlinear path to healing and closure from trauma — if we ever get there.

It’s been a year since President Biden took office and I am disappointed at his inability to act on his promise while on the campaign trail to “promptly roll back” his predecessor’s antipersonnel landmine policy. The president should confirm our stance as a leader in human rights by immediately prohibiting our military from acquiring and using landmines and destroying all stockpiles of these weapons. We as a country need to move far away from this reckless and archaic policy.

Antipersonnel landmines and other indiscriminate weapons are designed to do one thing: Kill now or kill later. I know this from experience.

From 1964 to 1973, the United States dropped over 2.5 million tons of ordnance over Laos during 580,000 bombing missions — equal to a planeload of bombs every 8 minutes, 24 hours a day for 9 straight years. This earned Laos the unwanted title of being the most bombed country per capita in history.

I was a part of the problem.

As a United States Air Force Veteran who served this great country for 38 years, I know firsthand the enduring impacts that these indiscriminate weapons have on their executors and on their human targets.

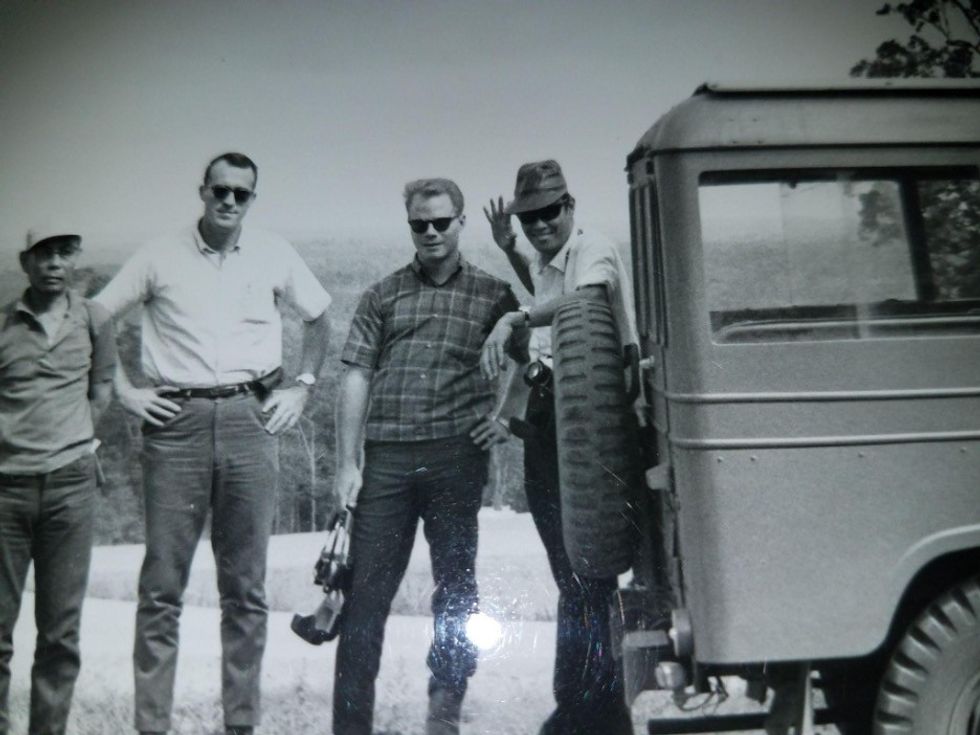

From December 1966 until December 1968, I was assigned to air bases in Thailand. The primary mission of the units to which I was assigned was to stop the flow of personnel and materials coming from North Vietnam through the “Ho Chi Minh Trail” to South Vietnam. The trail was located almost entirely in Laos.

At this time, I was a 26-year-old newly promoted captain who knew little more about the war in Vietnam than the majority of Americans at that time. I bought into the notion that there was a need to hold the line against the possible domino effect of a communist takeover across all of Asia if the United States didn’t stop them in Vietnam.

My naivete went back to my youth, growing up with a John Wayne view of America. We were the good guys, always on the right side and exercising our power only to ensure democracy and peace.

Within a few months, I was disabused of those notions.

In the wake of the U.S. bombings, 25 percent of the population of Laos became refugees. Countless historical and religious sites were destroyed, and innocent civilian blood was spilled on the soil of Laos. Families were displaced, separated, and forced to start a new life in a new culture, land, and language.

Those who escaped the constant pummeling of bombs have to deal with the emotional trauma and guilt of leaving their countrymen behind, knowing that there’s still a threat from unexploded ordnance and landmines.

The worst part for me is that an estimated one-third of the bombs dropped did not explode, leaving Laos contaminated with vast quantities of unexploded ordnance. To date, one percent has been cleared and over 25,000 people have been killed or injured since the bombing ceased. Other gifts left behind during this period include landmines and Agent Orange.

I spent 35 years of my life grappling with the guilt, horror, and trauma from the war and my only escape was to turn to alcohol and opioids. I worked with a therapist and found a way to live in solitude with the past and focus my energies on ways that can help resolve some of the legacies of war.

When I moved to Oregon, I became involved through the city in efforts to ease the resettlement of Laotians and met someone who looked familiar. On one of my visits to General Vang Pao’s headquarters, I was introduced to a 14-year-old interpreter for Vang Pao named Bruce. Here in Portland, Bruce was now Dr. Bruce Bliatout, the head of the county refugee and health administration.

Bruce and I, along with other members of the Hmong community, started the Immigrant and Refugee Committee Organization, which today serves a diverse group of immigrants and refugees from countries all over the world. It was through this organization that I became aware of the work of Legacies of War.

As Board Chair of Legacies, I’m proud of our team’s efforts to support bomb clearance and survivor and victims’ assistance. I’m also thankful that we are a member of the Steering Committee of the U.S. Campaign to Ban Landmine and Cluster Munition Coalition.

I urge President Biden to show American leadership and set the United States on a swift path to boldly join the 164 other countries who have made the humane decision to sign the international Mine Ban Treaty and the 123 countries who have pledged their support to the Convention on Cluster Munitions by the end of this year.

There are many NGOs and victims and survivor advocates like Legacies who stand ready to help consult the president and his team.

Mr. President, how many more lives must be unjustly taken from these weapons before you take action?