In the last two decades, Iran’s economic, social, and political conditions have steadily deteriorated. A brief period of recovery occurred after the signing of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in 2015 and the partial lifting of U.S. economic sanctions as a result.

The recovery stopped, however, after former President Donald Trump withdrew from the JCPOA and imposed new and harsher sanctions on Iran in May 2018.

Dwindling incomes, rising poverty, declining birthrates, thousands of unfinished projects, and idle industrial units reflect Iran’s worsening conditions. Even more reflective of Iran’s multi-dimensional crisis is the rise in the emigration rate of Iranians, especially among the most highly educated. According to Iran’s Minister of Health, 3,000 medical doctors have left the country. He warned that, if the trend is not stopped, the country’s health system could face a serious crisis, particularly as the COVID-19 pandemic persists. According to the Aftab News, one in three Iranians want to leave the country if possible.

Economic difficulties are the main cause of this migration. However, cultural restrictions and political repression also contribute to Iranians’ desire to move abroad. Hardliners who now dominate the government have responded to this trend by telling people, “If you don’t like us, leave the country.” Provoked by such an attitude, the director of Iran’s House of Music recently retorted: “If everyone were to leave, who would remain in Iran?”

Iran’s leaders, especially the hardliners who have had the last word in all Iran’s domestic and foreign policies, attribute their problems to the impact of U.S. sanctions. Clearly, sanctions have had a devastating effect on Iran’s economy, while failing to produce change either in the regime or its behavior.

Indeed, Washington has never been well-disposed towards Iran since the 1979 Islamic Revolution, and its policies towards Tehran have often been unwise and counter-productive. But Iran’s hardliners never ask whether Iran’s behavior might have contributed to U.S. hostility.

Yet, an objective observer will recognize that their mutual enmity and its negative consequences for Iran have resulted in part from major flaws in the foundational principles of Tehran's foreign policy.

Distorted Priorities

A principal source of Iran’s problems is the distorted priorities of its hardline leadership. Most states prioritize securing their own interests, including the well-being of their people. They may not succeed, but protecting and advancing the national interest is their primary objective. States even use ideology and values to serve their interests.

Not so for Iran’s hardliners. Protecting Iran’s interests as a state and people is not their main objective. Beyond retaining their hold on power, transnational objectives like fighting imperialism — meaning the United States— liberating Palestine and Al Quds, and achieving Muslim unity, are their priorities, even if pursuing them imposes heavy costs on the country’s citizens.

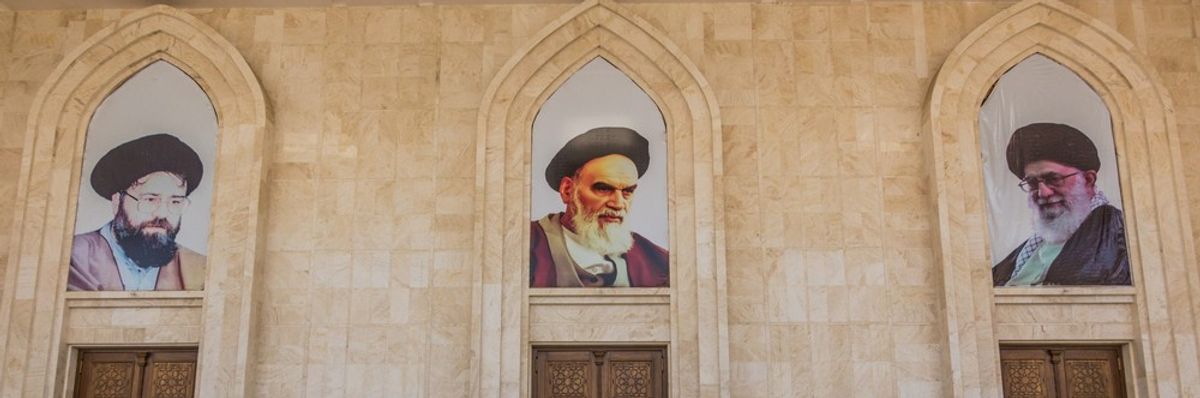

This is because hard-core Islamists, including Ayatollah Khomeini, have had no loyalty to Iran and its people’s welfare. They even see Iran’s pre-Islamic culture as a rival to Islam and hence a threat to their hold on power. For them, Iran is valuable only as an instrument to serve their vision of Islam.

This was the view of Mehdi Bazargan, Iran’s first post-revolutionary prime minister, who worked closely with Khomeini himself.A former member of Parliament and the son of Ayatollah Murtaza Motahari, Ali Motahari, more recently referred to Khomeini’s approach to the relationship between Iran and Islam in this way.

Early on, Khomeini further indicated that improving Iran’s and its people’s lot was not the revolution’s main goal. Rather, its mission was to restore Islam’s place in Iran and the world. The current Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, other hardline clerical and lay Islamists, as well as key members of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, share these views.

There are pragmatic forces in Iran that have tried to moderate and rationalize its policies. Figures like former Presidents Ali Rafsanjani, Mohammad Khatami and Hassan Rouhani represent these tendencies. However, their efforts have consistently been thwarted by hardliners.

It is only in light of these basic beliefs that key aspects of the Islamic Republic’s foreign policy can be understood. These include hostility towards the United States, the current refusal to talk directly with Washington, chronic enmity towards Israel, support for Hezbollah, Hamas and Islamic Jihad, and the Assad regime in Syria, all of which are seen as essential parts of the “Axis of Resistance (Mehvar e Moghavemat).

Distorted priorities and policies based on these fundamental beliefs are a major reason why Iran has come under international pressure and sanction. These policies, rather than its nuclear program per se, have contributed heavily to Iran’s current predicament.

Pakistan has developed nuclear weapons. But, because it is not engaged in an anti-imperialist crusade, nor does it wish to liberate Palestine or threaten Israel, it has escaped the kind of pressure or breadth of sanctions to which Iran has been subject.

Ignorance of the dynamics of international politics

Iran’s hardline leaders and foreign policy practitioners lack adequate understanding of international politics, especially the central role played by power balances among states. Believing their own propaganda, Iran’s most powerful leaders believe that a culture of resistance, martyrdom, and self-reliance enable them to defeat more powerful adversaries. They have relied on religious affinity and protestations of friendship and then have felt betrayed by other states’ behavior. When India, for example, voted to send Iran’s nuclear dossier to the UN Security Council in 2006, Ali Larijani, then Iran’s nuclear negotiator, expressed genuine surprise. He did not appear to realize that India, then engaged in an increasingly ardent courtship of Washington, would follow its own interests.

Even after forty years of setbacks, they persist in these patterns. Iranian leaders often appear astonished when other states counter their provocative actions by adopting hostile attitudes of their own. Similarly, they feel betrayed when neighbors use Iran’s international difficulties to pressure it, undermine its interests, advance their own goals, or when those whom they have supported in the past turn on them.

Iran lacks a consistently effective diplomatic cadre. The post-revolution purge of the foreign ministry meant its most experienced officers were dismissed or retired. Uneducated and inexperienced individuals replaced them, even at the levels of minister and ambassador. Gradually, more educated and sophisticated individuals entered the service, but they lacked experience in the art of diplomacy, and are often deficient in linguistic skills. Iran’s current foreign minister, for example, is incapable of conducting a conversation in English. Such shortcomings can be very damaging, especially when negotiating complicated legal and technical issues.

Unrealistic Streak

A lack of realism is another source of Iran’s problems in relations with other countries. Iran’s leaders have set goals which they cannot achieve. In the process, they have exhausted the country and the people economically, psychologically, and environmentally.

Even if Iran obtains some sanctions relief, its problems will not be resolved until and unless its leaders alter their priorities, adopt a more realistic foreign policy focused on protecting and advancing Iran and its people’s legitimate interests, and develop a professional, instead of the existing, largely ideological, diplomatic cadre.