Senator Patrick Leahy announced this week that he will be retiring from the Senate after 47 years. While most of the news stories about his decision focus on his important role on matters related to the judiciary and various impeachment trials, his departure will leave behind a big conscience gap in the U.S. Senate on foreign policy.

Leahy — and his highly empowered right hand, Tim Rieser — have been a dynamic duo since I came to town, 30-plus years ago. Leahy chaired or served as the top minority member on the appropriations subcommittee that wrote the annual budget bill for State Department and foreign aid, and, as the innocuous sounding but extremely powerful “clerk” of that subcommittee, Rieser has had the pen that writes the $55 billion-a-year law. (Leahy left this position to become Chair of the full Senate Appropriations Committee in January.)

Since 2002, when Congress stopped being able to legislate a foreign aid authorization act — akin to the annual National Defense Authorization Act, or NDAA — the “foreign ops” money bill became the primary annual legislation through which Congress impacts foreign policy. I and dozens of other activists in town quickly found that the most cost-effective way to get something done on foreign and sometimes military policy was to either talk to Sen. Leahy or to Tim.

Leahy and Rieser are two of all too few lawmakers or staffers on Capitol Hill who are openly horrified by war. Leahy first got involved when he saw victims of U.S.-backed wars in Central America. He legislated a “War Victims Fund” to try and make things less awful for some people. From there he used his power to cut off military assistance to abusive or aggressive regimes, prohibit exports of certain kinds of weapons, require State Department studies to explore peace processes, and so on.

Even Leahy and Rieser’s power is limited. They have had to pick their fights.

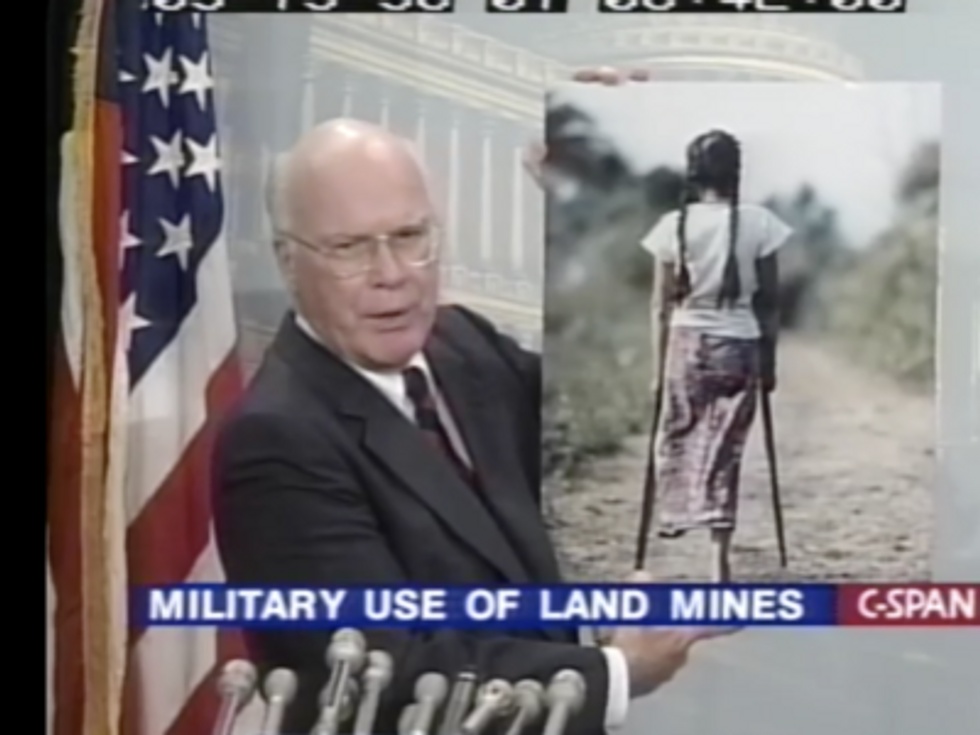

Senator Patrick Leahy briefs reporters on the need to outlaw anti-personnel land mines in 1996 (CSPAN screenshot)

They have picked some fairly big ones. As part of a campaign in the early 1990s that the late Mark Perry — a beloved QI staffer until his sudden death in August of this year — helped found and recruited them to, Leahy and Rieser worked tirelessly to prevent the U.S. military from using anti-personnel landmines around the world. These weapons have a disproportionate impact on regular people who come across them long after the battle has moved on. They did not have the legislative authority to take the weapons out of the U.S. military’s arsenal, but they used the foreign aid appropriations bill to ban exports of mines (arms sales being clearly in their jurisdiction). They also appropriated more and more money for demining, and called for inter-agency reports that put pressure on the DoD.

In 2006, after Israel rained cluster bombs down on southern Lebanon as part of an aggressive show of force against Hezbollah, leaving millions of unexploded cluster submunition duds in olive groves, farmland and backyards, Leahy and Rieser started working to stigmatize cluster bombs. They followed their landmine playbook, banning exports of weapons systems that are known to have a high dud rate and leave behind huge quantities of submunitions that fail to explode when dropped. These are particularly bad news, since they come in shapes that are attractive to curious children.

The United States never did join the 1997 treaty outlawing the manufacture, export, and use of anti-personnel landmines or the 2008 cluster bomb ban treaty, but Leahy and Reiser’s legislative actions effectively took the weapons out of the U.S. military’s arsenal.

Senator Leahy is also known for two foreign policy-related “Leahy Laws” — one that requires the United States to cut off U.S. military assistance if a military coup displaces a democratically elected government. This law, like any, requires vigilance and pressure — oversight by the Congress — to ensure that it is adhered to. In Honduras in 2009, and with General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s overthrow of the democratically elected Morsi government in Egypt in 2014, its application was fudged by the State Department (or White House). But it has provided useful leverage in many cases.

The other eponymous law is perhaps better known. In 1997, after failing to muster the political will in Congress to cut off all military aid to Colombia in the face of routine civilian massacres by U.S. backed forces in the war against leftist peasant rebels and narco-traffickers, Leahy introduced a law that was narrow enough to pass. It required the United States to at least refrain from providing military assistance — weapons, money or training — to particular units of the Colombian armed forces about which the United States had credible allegations of severe human rights violations. The law originally only applied to counternarcotics assistance. Over the years Leahy expanded it to include all of the many pots of U.S. government military assistance. In some years, that totals as much as $20 billion in taxpayer-funded aid.

The law is a lot like putting lipstick on a pig: messy and imperfect, and it is seemingly observed in the breach — for example, as far as is publicly reported, the Leahy Law has not resulted in the cutoff of aid to any of the Israeli border unit troops credibly alleged to have engaged in serious human rights violations or by units that engaged in disproportionately punishing assaults on civilians in Gaza. But the senator has created an incentive for accountability, and a way to limit the liability of the American taxpayer. He has stayed focused on it over the years, working to revise and press and prod the State Department for ever better implementation.

We need a new generation of Leahy-Rieser combinations — members and staffers who care and who will use their power as creatively and impactfully to lessen the horrors and injustices that are a daily part of America’s military empire.