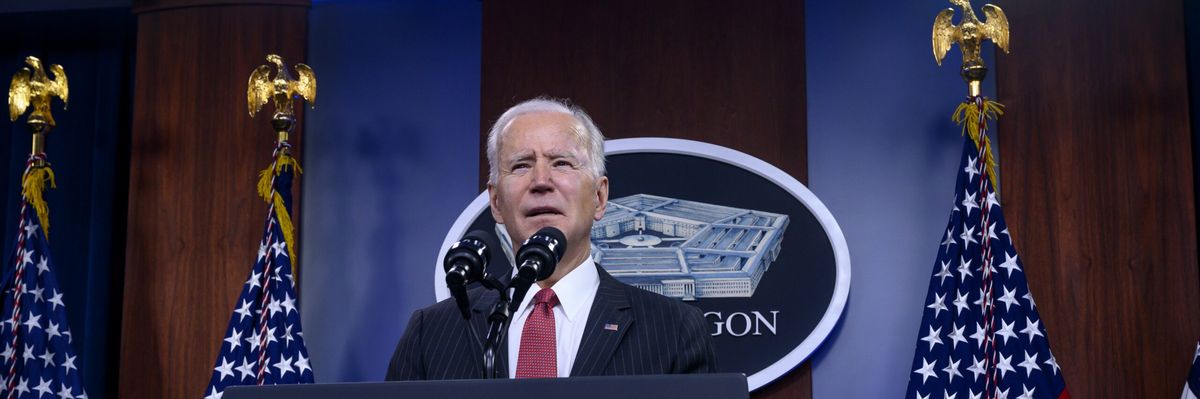

President Joe Biden this week engaged in the difficult task that has faced many presidents: he had to explain how his administration bungled a foreign policy decision that threatens to make Americans less safe as well as create a humanitarian crisis. While he did not apologize, he was “straight with” the American people: “This did unfold more quickly than we had anticipated,” he said. Having agreed to remove all U.S. troops by the end of August, he now has to quickly redeploy the military to remove U.S. personnel and Afghans who have assisted them as the Taliban took over Kabul on Sunday.

While the scenes in Afghanistan have been horrifying and much has been said about Biden’s decision to withdraw and the process by which it has been conducted, it’s also important that we take a wider view of why the United States has stayed so long in Afghanistan, and what that means for competing war powers granted to both Congress and the president in the Constitution.

Accountability for the failures in Afghanistan needs to go well beyond this poorly executed withdrawal and the current president. The bigger problem relates to war powers and how presidents have a long history of acting without receiving a great deal of push back or accountability from Congress.

This issue goes well beyond the Biden administration or even the post-9/11 presidencies. Harry Truman defined the Korean War as a “police action”; Richard Nixon sent troops into Cambodia despite Congress expressly forbidding it; Ronald Reagan sent Marines to Lebanon without authorization; Bill Clinton also bombed Kosovo without congressional authorization and a federal judge dismissed efforts by Congress to use the judiciary to compel him to stop. Presidents have engaged in a variety of unilateral military actions since 1950 without Congress doing a great deal to impede them or draw down forces if the operation is failing to achieve even the vague objectives.

This expansive understanding of executive power was then consistently supported by the Office of Legal Counsel, starting before World War II with then-Attorney General Robert Jackson’s controversial justification of President Franklin Roosevelt’s destroyers for bases deal. By 9/11, George W. Bush’s OLC had decades of precedent to draw from when it started broadening the definition of his Article II power. Presidents have had the luxury of creating their own definitions of their powers because Congress has failed to challenge them by constraining presidential unilateralism or passing legislation that would create legal restraints.

More problematically, via the 2001 and 2002 Authorizations for the Use of Military Force, Congress provided the president broad powers to wage war indefinitely.

The language in these AUMFs makes it difficult for Congress to hold the president accountable. For example, the ambiguous use of the term Iraq and the Iraqi regime opened the door to exactly what happened: well after Saddam Hussein’s regime had fallen and a new one installed, U.S. presidents could continue to use the authorization for a variety of operations unrelated to the original invasion in 2003.

In sum, Congress has been ceding its war powers since the beginning of the Cold War, shirking its role in war and decisions associated with how and why presidents deploy the military in operations large and small.

At present, there is little stopping Biden from making any unilateral decision he wants with respect to Afghanistan. Based on the current understanding of the president’s Article II power and the broad reading of the 2001 and 2002 AUMFs, the legal constraints on presidents are shockingly limited. For that reason, presidents use these powers to carry out all sorts of operations from smaller ones like drone strikes against terrorists to the on-going operation against ISIS.

The unilateral power of the president has to change. Senators Bernie Sanders, Mike Lee, and Chris Murphy recently introduced a bill aimed at helping Congress reassert its war powers. As Murphy has said, since the passage of the 2001 and 2002 AUMFs, presidents have launched military operations in “more than 20 countries” without “a comprehensive public debate about the wisdom of the decision.” Among many other fixes, the new bill attempts to define the term “hostilities” in order to close the loophole that the executive branch has exploited in expanding the U.S.’s post 9/11 military campaigns across the globe.

While the bill has a long way to go for it to become law, it’s a step forward towards containing presidential unilateralism that has grown over many decades and received support from both Democratic and Republican administrations alike. Increasing the legislature’s role in deliberation on the big questions associated with U.S. interests and national security may force the executive branch to develop and implement a more sound grand strategy based in diplomacy rather than continuing the reactive and overly lethal foreign policy that has mired the United States in endless wars.