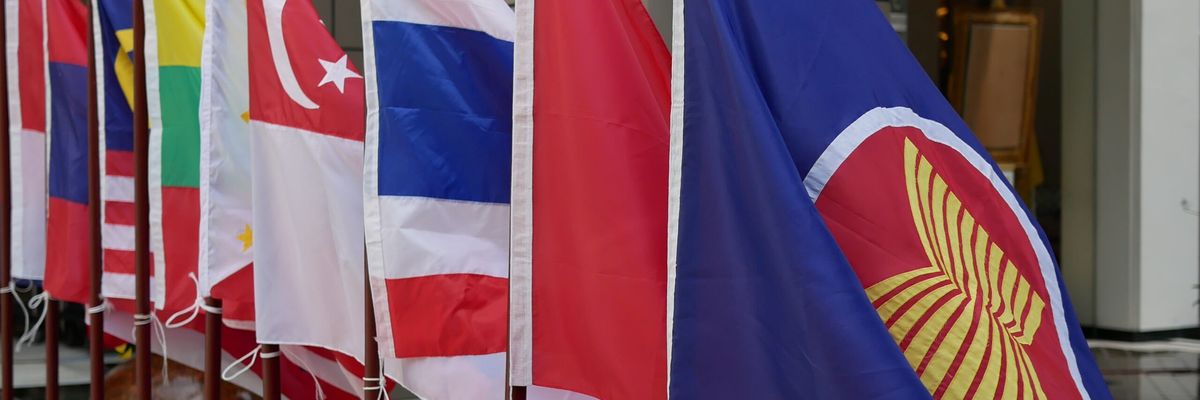

Just last week Japan ratified the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, one of the largest free trade agreements in the world among 15 countries including all ten ASEAN countries and China. Many see the RCEP, which is projected to eliminate a variety of import taxes for 20 years, as a China-backed alternative to the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a U.S.-designed planned trade agreement that excluded China and included four Southeast Asian countries, namely, Singapore, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Brunei.

Southeast Asia has traditionally functioned as a hotspot of rivalry between major powers and may do so again. Beijing and Washington each have intricate ties to the region but ASEAN countries do not want to be divided via further tension and competition between the United States and China in Southeast Asia.

But the United States is already lagging behind in Southeast Asia and its diplomatic and political capital in the region has eroded during the last four years. It has opted out of the RCEP and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership. President Donald Trump attended a special U.S.-ASEAN summit in Manila in 2017, but he did not attend any of the four East Asia Summit meetings during his term. The United States has been operating without ambassadors in four ASEAN countries and is the only major country without a permanent presence at the ASEAN Secretariat. For the Philippines and Indonesia, getting too close to Trump was seen as a political risk, which is why Indonesian President Joko Widodo, never visited Trump at the White House.

The Biden administration is presently working to remedy the problem and has declared that regaining allies and partners while pushing back adversaries is its top priority in foreign policy. ASEAN countries are quite keen on strong relations with both China and the United States and they would welcome a robust U.S. presence in the region, but only in the correct manner. They are all attempting to maximize both capacities as Southeast Asia and the Indo-Pacific region are deemed to offer both superpowers a plethora of engagement space.

Biden's first foreign-policy move in Asia was to host the Quadrilateral meeting of the United States, Australia, Japan, and India — and elevate it to a leader-level summit — which the ASEAN states eagerly observed. While the Quad leaders reiterated ASEAN's significance, there are questions inside ASEAN regarding the Quad's strategic purpose and if it will take steps that are incompatible with ASEAN's goals. ASEAN's relationship with the Quad has remained ambiguous and unpredictable until this point. The Quad will inevitably bring up the question of whether Biden's Indo-Pacific strategy will differ from Trump's anti-China approach.

Indeed, Southeast Asian countries are understandably concerned about China's actions in the South China Sea, and they have also realized that China will play an important role in their future, both bilaterally and regionally. Despite Washington's largely bipartisan view of China as a threat to the United States' long-standing hegemony, Southeast Asians perceive China as a critical partner in their development ambitions.

Southeast Asians are also aware of President Biden's warning about authoritarianism in China. On the ground, however, due to the policy of non-interference and a lack of interest in China's domestic affairs, no Southeast Asian nation is particularly worried about China's political system. Former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, and his successor, Antony Blinken, have both said China is committing genocide against Muslim Uyghurs in Xinjiang. No ASEAN country has repeated this accusation. No Southeast Asian nation, including Indonesia, which has the world's largest Muslim population, regards China as an ideological foe. In fact, ASEAN leaders would sympathize with Chinese President Xi Jinping's remark that every country has the ability to choose its own development path.

Furthermore, Southeast Asian nations want to maintain their leading role and firmly believe that ASEAN countries should be in charge of their regional affairs. The presumption here is that world leaders trust ASEAN countries and are willing to cede leadership in some areas of regional affairs to them. ASEAN's ability to retain strong connections with all major countries — including the United States, India, Japan, Russia, China, and the EU is — is crucial to its legitimacy. Consequently, ASEAN does not wish to take sides or be pushed to do so. The inevitable result of taking one side is the alienation of the other.

Southeast Asians want to see Americans and Chinese collaboration in their region. A few years ago, Xi advocated for a “new kind of great-power relationship” with the United States based on “win-win solutions.” Biden has declared that his administration favors "competition over conflict" with China and that he is "prepared to engage with Beijing when it is in America's best interests." According to Blinken, the relationship between the United States and China will be "competitive when it should be, collaborative when it can be." The fact that Blinken has been using the phrase "free, open, and inclusive Indo-Pacific" more frequently — "inclusive" being a code term in the ASEAN outlook on the Indo-Pacific for keeping the door open for China — is a clear signal of the influence of ASEAN countries and the Biden administration’s decision that it does not want to isolate or restrain any resident power.

Of course, countries in this region had already demonstrated how they can influence relationships and turn adversarial relationships into friendship. Industry, infrastructure, maritime security, piracy, climate, environment, green energy, natural disasters, COVID-19, youth exchanges, and other issues are all up for discussion between Washington and Beijing. While this will have minimal impact on their global rivalry, it might change the tone of US-China relations in Southeast Asia. In the view of ASEAN, that would suffice.

President John F. Kennedy and Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. in 1961. (Robert Knudsen/White House Photo)

President John F. Kennedy and Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. in 1961. (Robert Knudsen/White House Photo)