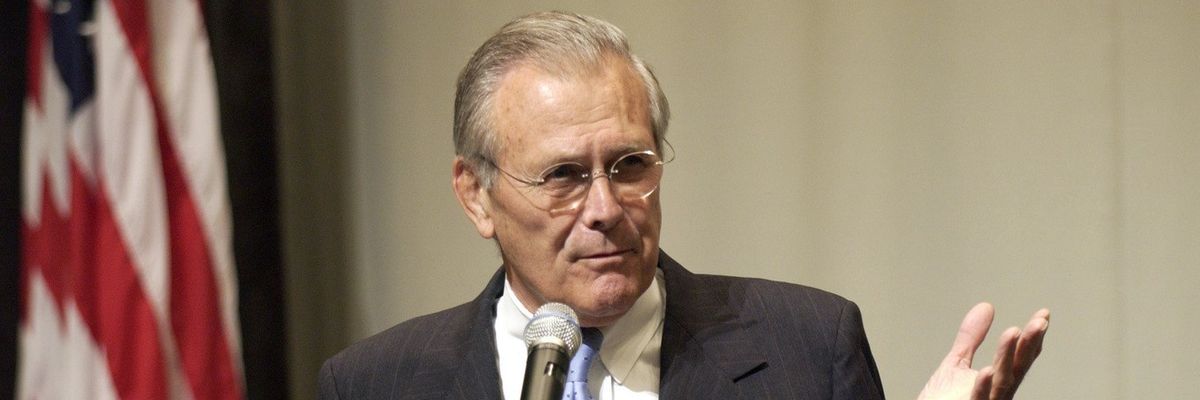

Donald Rumsfeld, a two-time Secretary of Defense under Ford and Bush, former permanent representative to NATO, and former Congressman, died at the age of 88 on Tuesday, according to an announcement from his family.

Rumsfeld was one of the chief architects and defenders of the illegal invasion and occupation of Iraq, and he was also responsible for approving illegal interrogation methods that led to the torture of detainees. A longtime ally of then-Vice President Dick Cheney, Rumsfeld was one of the officials most responsible for the greatest American foreign policy debacle since Vietnam, and he became a symbol of the failures of the Bush administration’s management of the Iraq war. He was one of the chief war criminals of the Bush era, and he was never held accountable for the devastation he helped to cause.

Educated at Princeton, Rumsfeld briefly served in the Navy and then in Congress. He served in the Nixon administration, and then became White House chief of staff to Gerald Ford. Rumsfeld then brought Cheney into the Ford White House when he went to run the Pentagon the first time. Returning to government service in 2001, he served five years under George W. Bush until he was forced out following the Republicans’ drubbing in the 2006 midterm elections.

Rumsfeld was enamored with a so-called “light footprint” approach to war, and under his leadership the military was unprepared for the open-ended occupations in Iraq and Afghanistan that they were ordered to carry out. His plans for the invasion were inadequate in large part because he imagined that the U.S. would be fighting a reprise of Operation Desert Storm. During the autumn before the invasion, he said, “The idea that it's going to be a long, long, long battle of some kind I think is belied by the fact of what happened in 1990.”

He infamously dismissed the possibility that the war would drag on beyond one year: “Five days or five weeks or five months, but it certainly isn't going to last any longer than that.” He slapped down Gen. Eric Shinseki’s assessment that hundreds of thousands of troops would be needed to occupy Iraq, saying, “the idea that it would take several hundred thousand U.S. forces I think is far from the mark.” Because he never took seriously the inherently destabilizing effects of a war for regime change, he made no effort to prepare for what would come next. His self-serving claim that “you go to war with the army you have, not the army you might want or wish to have at a later time,” was an attempt to deflect from the fact that the army the U.S. had at the time was the one that Rumsfeld wished to have, and the war was one that the United States had chosen to start.

Rumsfeld was a wartime Secretary of Defense almost the entire time he served in the Bush administration, but his leadership in wartime was sorely lacking. As Lt. Gen. Gregory Newbold said of him, Rumsfeld made decisions “with a casualness and swagger that are the special province of those who have never had to execute these missions— or bury the results.” Rumsfeld embodied the hubris and recklessness of the Bush administration. His approval of brutal interrogation methods meant that he also took part in the administration’s criminal behavior. Human Rights Watch summed up his role in the administration’s use of torture this way: “Defense Secretary Rumsfeld created the conditions for members of the U.S. armed forces to commit torture and other war crimes by approving interrogation techniques that violated the Geneva Conventions and the Convention against Torture.”

As Secretary of Defense, Rumsfeld also presided over the expansion of U.S. security commitments in Europe with the second round of NATO expansion that took place in 2004. He cheered on Ukrainian efforts to join the alliance when he was still in government. After leaving government, he continued to advocate for continued NATO expansion to include Ukraine and Georgia. Just as the Bush administration was doing at the time, Rumsfeld called for granting Ukraine and Georgia Membership Action Plans (MAPs) in 2008. In the end, the decision to open the door to alliance membership at the Bucharest summit contributed to the outbreak of war between Georgia and Russia later that year. This is a reminder that Rumsfeld’s strategic judgment was just as flawed and poor in other regions as it was in the Middle East.

The Iraq war was an unnecessary and illegal preventive war, and Rumsfeld’s part in waging it defines his legacy as one of the top leaders responsible for this crime. Unlike an earlier generation of policymakers chastened by their failures in Vietnam, Rumsfeld had no regrets about running a war that killed thousands of Americans and hundreds of thousands of Iraqis while also displacing millions more. In his memoir, Known and Unknown, he continued to support the war without qualification: “Ridding the region of Saddam’s brutal regime has created a more stable and secure world.”

Even as he was writing those words, the war he helped to start was creating the conditions that would lead to the rise of ISIS and the destabilization of Syria. His unrepentant attitude was typical of top Bush administration officials, and Rumsfeld’s uneventful retirement shows that there is no real accountability in our system for disastrous policy failure and war crimes.