In 2014, Dick Cheney visited House Republicans and spoke about the Obama administration’s supposed weakness on defense spending and hawkishness. The Washington Post’s Robert Costa focused on two libertarian-leaning Republicans who did not like the scene that day.

Referring to then-Congressman Justin Amash -- the Michigan congressman had left the GOP in 2019 and Congress in 2020 and today is a registered Libertarian — and Rep. Thomas Massie (R-K.Y.), Costa wrote, “The young and dovish libertarians sat silently on Tuesday morning as former vice-president Dick Cheney addressed a gathering of House Republicans on Capitol Hill. When Mr Cheney finished his remarks on foreign policy and took questions, they eyed the door and declined to challenge him.”

Massie had little to say afterwards other than the “primary thrust” of Cheney’s talk was about increasing the U.S. defense budget, and that he disagreed. “We need to spend less money on everything,” Massie said.

When Amash was asked if Republicans should stop listening to Cheney, he replied “Yeah.” His worldview is that we should be in countries around the world and have armed forces everywhere,” Amash added, ”and most Republicans don’t agree with that.”

Amash had reason to frame where his party stood on foreign policy in such a way at the time. Despite the friendly reception the former vice president received from most GOP members that day, by Obama’s second term, many Republican voters and members of Congress had opposed the president’s interventions in Libya and Syria. Being against Obama’s wars had become part of a Tea Party ethos that defined the party’s base in 2014 more than the Bush-Cheney neoconservatism that had dominated before.

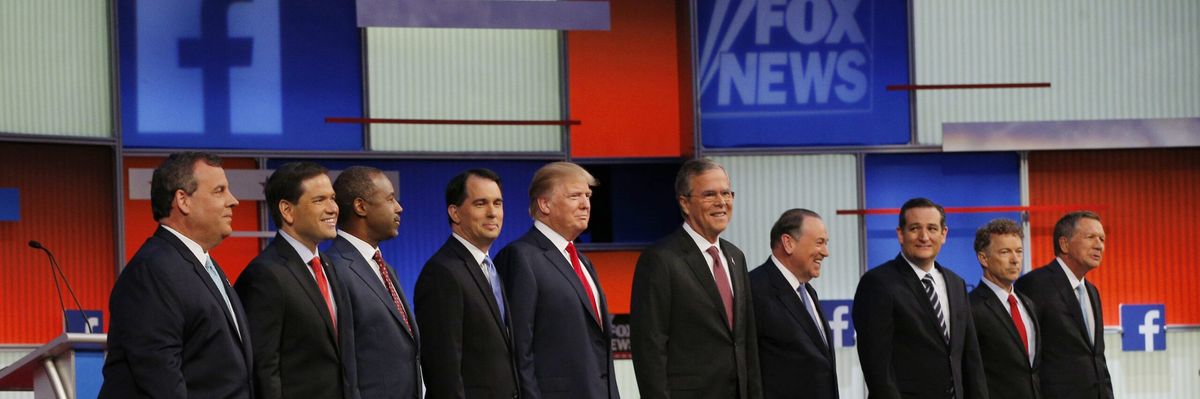

But it was still an open question as to what Republican foreign policy might look like moving forward. With 2016 only two years away, rumors of Jeb Bush, Marco Rubio and Chris Christie — all hawks — entering the GOP presidential primaries were in the air. The only peace or restraint advocate to enter the race, Sen. Rand Paul, was such a worry to many in the party establishment before the rise of Trump, that uber-hawk Sen. Lindsey Graham had reportedly entered the race simply to stop Paul from gaining any momentum. If Paul was defeated, only hawks would be left in the race, and such a Republican president could restore the Cheney wing of the GOP to dominance.

Then Trump happened.

“They lied,” Trump asserted about the George W. Bush administration’s drive to war in Iraq during a primary debate in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina. “They said there were weapons of mass destruction, there were none. And they knew there were none.”

Many wrote off Trump for making such comments in “Bush country.” But he then went on to win the state’s primary by 35 percent, with Marco Rubio trailing at a distant second at 22 percent. Trump would go on to defeat Hillary Clinton in the general election in South Carolina 55 to 41 percent.

South Carolina became Trump Country.

For four years, Trump did not always follow his own “America First” foreign policy rhetoric. But the notion that it was a conservative cause not to start new wars, which Trump didn’t, was something Tea Party libertarians like Amash and Massie had long argued.

Still, there were plenty of hawkish politicians and pundits eager to keep the GOP the War Party. As Costa wrote in 2014, “Amash and Massie, by avoiding a back-and-forth with Cheney in front of their colleagues, underscored the difficult political terrain they face within their own party as they try to change it. Younger grassroots types may increasingly be with them, and averse to the Bush-era foreign policy approach, but most GOP lawmakers remain wary of shifting their traditional values on foreign policy.”

In 2021, those “traditional” foreign policy values have shifted considerably. This doesn’t mean the old guard has vanished. Jim Antle recently examined how establishment hawks are currently trying to put the Bush-Cheney band back together again. “Left unspoken is that many (Never Trump Republicans) hope that the party consensus will revert back to preventive war, rapidly expanding commitments for mutual defense with countries with little military might or connection to the vital interests of the United States, and a lower threshold for the use of force than prevailed under Ronald Reagan or George H.W. Bush, much less older Republican intervention skeptics such as Robert Taft.”

Hawks might be successful. But unlike the aughts, when the Bush administration had overwhelming public support after 9/11 and a massive left-wing antiwar movement that emboldened conservatives in their support for war, most Americans today are tired of what Trump denounced as “endless wars,” including Republicans.

When President Joe Biden announced a full withdrawal of U.S. forces from Afghanistan by September 11 of this year, the normal rules of partisanship would usually dictate that Republicans would stand in opposition. Some did. GOP hawks like Congresswoman Liz Cheney, Sen. Lindsey Graham, and columnist Bret Stephens called the decision to end a 20-year war “cut and run,” for however few Republicans are still listening to these people.

More importantly, Trump called Biden’s Afghanistan withdrawal a “wonderful and positive thing to do.” Trump’s primary beef with Biden is that he is taking too long to pull troops out, surpassing the Trump administration’s original May 1 deadline.

In other words, if Biden is doing something antiwar, Trump’s impulse is not to be reflexively pro-war like Cheney and Graham, but to remind Americans that he’s even more antiwar than the current Democratic president. Not surprisingly, a majority of Republican voters are also on board with ending America’s longest war. An April 21 Morning Consult poll found that 52 percent of Republican respondents favor withdrawal compared to just 33 percent who oppose.

This is light years away from Bush-Cheney.

When Republican Congressman and libertarian icon Ron Paul first ran for president in 2008, the GOP establishment rejected him precisely for his antiwar stance. His son, Sen. Rand Paul, told Fox News in August, “I think the party that wasn’t ready for my dad in 2008 actually is much more accepting of the positions of less war and military intervention, but, largely because of President Trump expressing similar views.”

In 2014, Republican Congressman Justin Amash and Thomas Massie fought for non-interventionism in their party but knew its leaders were eager to revert to a permanent war stance asap. Little did they know at the time that Trump, however imperfect, would soon bulldoze the GOP elite, neuter their power over the party’s base, and make peace more of a conservative value than war for a majority of Republican voters. Dick Cheney wishes he had a smidgen of the influence over conservatives that Trump does today.

You don’t have to like Trump if you’re antiwar, but he did oust the ancien regime and revolutionize the way Republicans at large think about foreign policy. Anyone antiwar should at least appreciate this singular surprising achievement.

Screengrab via niacouncil.org

Screengrab via niacouncil.org Screengrab via niacouncil.org

Screengrab via niacouncil.org