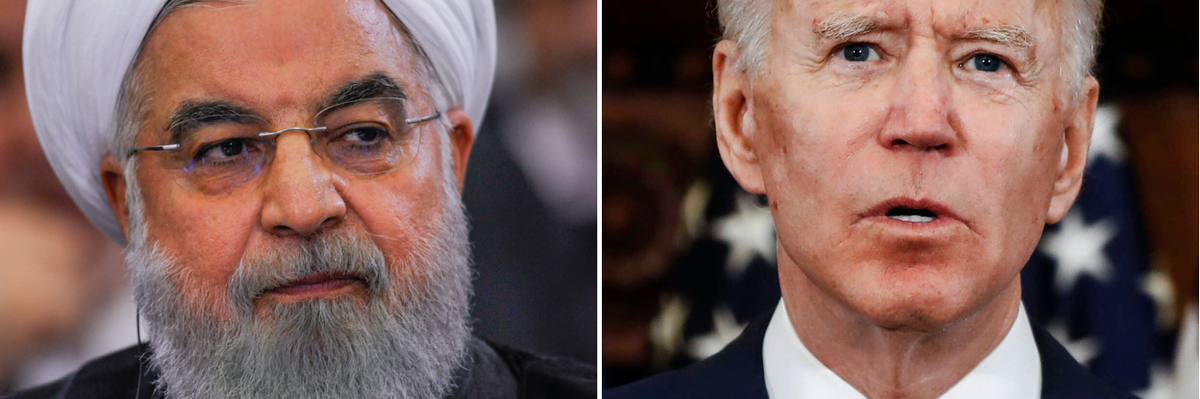

The new Biden administration has put the Iran File at the top of its “must dos” in foreign policy because of two factors. First, it is imperative to keep Iran from acquiring a nuclear weapons capability or even to get close to it. Indeed, Washington will not let that happen even if it means resorting to military action. Second, the intensity of U.S. media coverage and political commentary on the Iranian nuclear program requires that it be dealt with post-haste.

This Sunday, President Biden replied “No,” when asked in an interview whether the United States would “lift sanctions in order to get Iran back to the negotiating table.” Which means, “They have to stop enriching uranium first.” Meanwhile, Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei has said that “If they want Iran to return to its commitments...America must completely lift sanctions, and not just in words or on paper.”

Both statements could be the start of an informal bargaining process, with each side just staking out its maximalist positions. But don’t bet on it. Because of the rivers of bad blood separating the two countries, that interpretation is implausible. Instead, we most likely have what in Hollywood Western movies was called, a “Mexican stand-off” — both sides unwilling to de-escalate unless the other makes the first move. The great risk, however, is that it could turn into a dangerous game of chicken, with war the possible result.

So what should the Biden administration do? Time is also a constraint, with concern that Iranian nuclear developments not pass the point of no return while Washington makes up its mind. Secretary of State Antony Blinken has said, “if Iran continues to lift some of these restraints imposed by the [2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action -- JCPOA], that could get down to a matter of weeks.” Blinken did point out “that the fissile material is one thing. Having a weapon that they can actually detonate and use is another.” That is a valid distinction, but in a world where perception of threats is often mistaken for reality, that’s unlikely to make a difference.

The simplest first step would be for Biden, by a stroke of his pen, to reverse President Donald Trump’s May 2018 withdrawal from the JCPOA. That would challenge Iran to de-escalate. But he has seemingly ruled that out. Indeed, beginning in last year’s presidential campaign, both he and his top officials have been consistent on the requirement that Iran act first.

Despite demands to deal promptly with this issue, the new administration needs time to find its “sea legs” and craft policies that go beyond place-holding rhetoric that, with luck, doesn’t prejudice policy choices later on. Even Secretary Blinken acknowledged on January 31 that he hadn’t “seen the actual intelligence yet” on the timing of the Iranian nuclear program. Notably, President Biden also avoided mentioning it in his major foreign policy speech on February 4.

Furthermore, any serious U.S. approach will have to deal with events during the past several years that can’t just be wished away, plus Washington objectives regarding Iran that go beyond nuclear issues. Notably, Obama, Trump, and now Biden officials have all referred to Iran’s “malign activities” in the region. Iran has its own list of grievances.

Bad blood began in earnest immediately after the conclusion of the JCPOA in 2015. Washington and Tehran each soon accused the other of reneging. Iran continued testing ballistic missiles, an affront to Obama, although it was not required to stop testing by the relevant UN Security Council Resolution (2231). For its part, under the JCPOA, the administration did remove sanctions related to Iran’s nuclear program in 2016, but promptly imposed others.

Complicating matters is the fact that a major determinant of any U.S. approach is domestic politics, which have a greater impact in the Middle East than in any other part of the world. Thus, Obama managed to conclude the JCPOA but he faced strong political opposition at home. This was underscored by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s March 2015 speech to a joint session of Congress in which he asked members to defy the president of the United States and was repeatedly cheered.

Furthermore, Washington’s key partners in the Middle East oppose any rapprochement between the United States and Iran, and not just because of their concern about nuclear issues. Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates want to prevent any serious competition for influence in the Persian Gulf. More important, Israel wants not just to ensure its own security, including trammeling Iran’s nuclear and ballistic missile programs, ending Teheran’s support for Hezbollah in Lebanon and Hamas in Gaza, and retaining its “qualitative military edge” in the region. It also wants to forestall any country becoming a serious competitor for power in the Middle East — that’s geopolitics, not security.

The argument that Iran could be a serious competitor for regional hegemony rests on shaky grounds. Tehran does enjoy significant influence in Lebanon, Syria, and Iraq — though these are all more or less “failed states,” not serious contenders for power in the region. The Islamic Republic’s broader ambitions came apart more than two decades ago, when it tried and failed to export revolution across the Middle East and Central Asia.

Moreover, Iran’s military capabilities are modest, though they are inflated by some outside analysts, in part to justify swamping the Arab countries of the Persian Gulf with advanced weapons that would be of virtually no utility in dealing with genuine Iranian challenges — notably its promoting “destabilization” or engaging in “terrorism” (in which Iran is not the only guilty party). Likewise, Iran poses no economic threat. At the same time, given its relative advances in universal education, technological know-how, entrepreneurship and middle-class values compared to most of its Arab neighbors, regional states (but not Israel) do have a legitimate concern with Iran’s potential for modernization and integration into the global economy.

With all the conflicted interests and lack of any serious interaction among the region’s contending powers across political, strategic, sectarian, and religious lines, Washington’s long-term goals, centered on fostering as much stability as possible, are currently well out of reach. Nevertheless, it might be possible to take some crisis management steps, such as forging a multilateral agreement on freedom of navigation through the Strait of Hormuz (which is in every country’s interest) or an incidents-at-sea understanding (done either tacitly or quietly at the level of individual ships), as the United States and Soviet Union concluded in 1972.

This leaves the following: how much time, energy, and domestic political capital will President Biden devote to the Iran File, beyond trying to get the Iranians to put their nuclear enrichment on hold? In any event, without major U.S. sanctions relief, Iran’s reversing its recent progress in its nuclear program almost surely will not happen.

Biden faces strong domestic political hostility to doing anything that could be depicted as a concession to Iran, even if it serves U.S. national security interests, as the JCPOA clearly did. His domestic critics, as well as Iran’s regional rivals, also demand that non-nuclear issues be part of any agreement with Iran, which would undermine any prospects for freezing, let alone rolling back, Iran’s nuclear program in the absence of much more significant U.S. concessions. Demanding the “best” will kill the “good.”

The good news is that Biden has appointed Rob Malley, most recently head of the International Crisis Group and highly regarded by the vast majority of Washington’s Middle East analysts, as his Special Envoy for Iran. But he starts out not knowing for certain whether the Iranians are prepared to “deal,” a precondition for serious negotiations. If so, they will need to begin out of the public eye, as were the early talks that led to the JCPOA.

But assuming that something does become possible with Iran that meets U.S. interests, though not necessarily those of regional partners, Malley must be able to count on President Biden’s willingness to take the domestic political heat. Otherwise, the standoff may just continue. If it does, Tehran may not understand the limits to its uranium enrichment program beyond which it dare not go without risking military action by the United States.