Presidents’ Day 2021 will carry some ironic hues — particularly in the immediate wake of a deadly riot at the U.S. Capitol, the House impeachment of the former president, and the inauguration of a new chief executive. The office of the American presidency is clearly in a fragile state.

Some have pointed fingers primarily at the autocratic and narcissistic tendencies of the last incumbent, but his behavior and actions were enabled by the excessive and extra-constitutional power that the presidency has acquired over the last century, especially in the last 20 years.

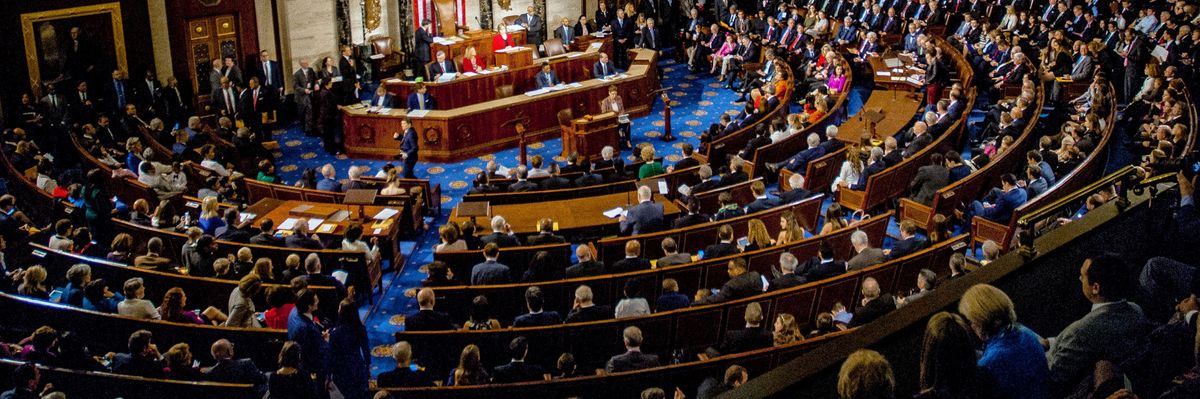

The 147 Republican votes to reject a pro forma certification of the election results — even in the face of a clumsy, incited riot that many have called an outright insurrection — demonstrates how a modern-day president can use his bully pulpit to intimidate lawmakers into doing his bidding. Contrary to conventional wisdom, President William McKinley — not his more charismatic successor Teddy Roosevelt — first used the new national network of newspapers at the turn of the 20th century to powerfully speak to voters across the nation to get his way in Congress. He wanted Congress to give him carte blanche in the conduct of the Spanish-American War, and he got it.

The successful use of the media in order to go over the heads of Congress is probably the most important factor in the warping of the founders’ expectation that the legislature would be the most powerful branch of government. The founders originally conceived the executive’s role as more limited to executing laws approved by Congress, both in peacetime and wartime.

However, other more formal expansions of presidential power followed, beginning in the mid-20th century — at first in the national security realm, and later spreading to the domestic one. Originally, the founders had conceived of the president's role as commander in chief as merely being the commander of military forces on the battlefield. Up until 1950, Congress had declared all major wars, but this changed when Harry Truman deliberately decided to stretch his power as commander in chief to unilaterally take the nation to war in Korea, with no such declaration.

Unfortunately, Congress let him set this bad precedent. Ever since, war has been primarily the purview of the executive, dragging Congress along for the ride with no more declarations. Even Alexander Hamilton — the greatest proponent of executive power, to the point of being an outlier, at the Constitutional Convention — noted in the Federalist Papers that Congress should decide whether the nation went to war, and the president would only execute that decision.

Also at mid-century, Congress passed the National Security Act of 1947, which gave President Truman and future executives beefed-up national security bureaucracies more beholden to him — including his own intelligence agency — to perform dirty tricks overseas with little congressional oversight. Nevermind that these actions could lead to U.S. involvement in wider conflicts.

The combination of expanded authority over war powers and the creation of a muscular executive bureaucracy to carry it out, created a powerful imperial presidency, as historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. first called it. Because the now-mammoth executive branch, comprising 99 percent of federal employees, is the only one of the three branches to have resources to implement government policies on the ground, it can now run circles around the other branches, both in national security and increasingly in domestic affairs too. For example, executive agencies traditionally negotiated their budgets with the appropriate congressional committees with little White House involvement. But the creation of a president’s budget under the Budget and Accounting Act of 1921 rendered Congress’s budgetary role one of puttering around the edges of the executive’s blueprint — once again abdicating an important legislative power to the president.

In addition to allowing the president to usurp its war power, Congress has also abdicated its power to ratify treaties with foreign countries using a two-thirds vote of the Senate. In recent times, presidents have signed many more executive agreements with foreign countries than they have submitted treaties to the Senate for ratification. Executive agreements are nevertheless not mentioned in the Constitution and either are approved by the lesser hurdle of a majority of both houses of Congress or get no congressional approval at all (though most do).

Congressional power has been eroding for more than a century. However, the events of January 6 — when the executive was accused by the majority parties of Congress of inciting a physical attack on a co-equal branch of government, and 147 Republicans still supported his cockamamie attempt to overturn a legitimate election — should be a powerful wake up call that Congress needs to take back its constitutionally granted powers. The next president trying to wield even more power at their expense might not be so ham-handed.