Democracy in the world is not doing well, and hasn’t been for the last several years. The watchdog organization Freedom House has recorded a 14-year decline in the political rights associated with democracy as well as other liberties that define a free, pluralistic society. Similarly, the Economist Intelligence Unit registered last year the worst score in its “Democracy Index” since it began compiling the figure in 2006.

This dark trend ought to be of concern first of all because of the inherent value of political rights and of the ability of people to choose their own leaders. The subject also matters in many indirect ways for U.S. foreign relations and U.S. interests abroad. One of the most widely accepted theses among scholars of international relations, for example, is that of the democratic peace, according to which democracies do not fight wars against other democracies.

And yet, little has been heard in this year’s U.S. election campaign about the state of democracy in the world and how to improve it — apart from observations about President Donald Trump’s evident liking for dictators over democratically elected leaders. The inattention reflects one of the biggest doctrinal turnarounds in recent years in Trump’s own political party, bigger even than changes in Republican views about trade and tariffs.

It wasn’t that long ago — during the last previous Republican presidency, that of George W. Bush — that Republican foreign policy was dominated by neoconservatives, for whom promotion of democracy abroad was a rather big thing. Admittedly, it was not an overriding principle for the neocons, for whom support for Israel under a right-wing government also was a defining characteristic. That meant that Palestinians would always be an exception to any neocon program to bestow the blessings of democracy on others — a point on which Trump’s policies represent continuity within the party.

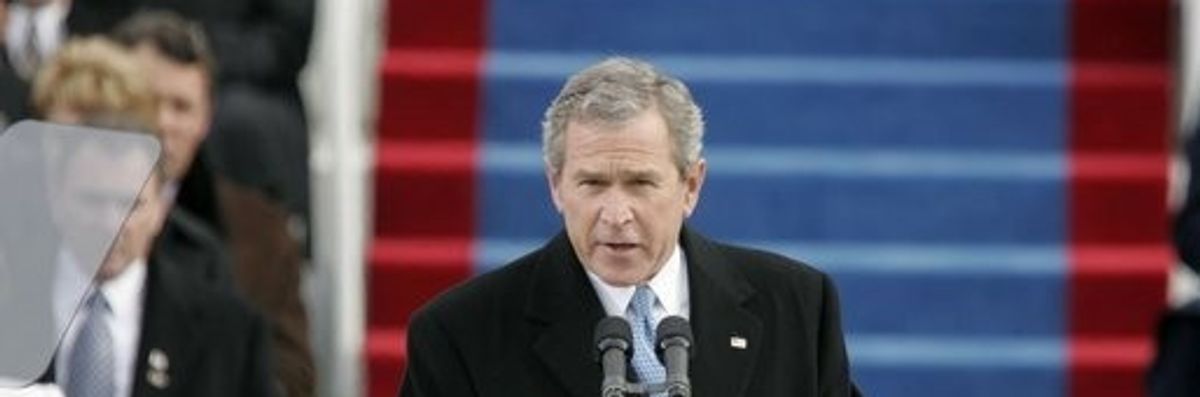

Nonetheless, the urge to put a more democratic imprint on the rest of the world was genuine. Bush’s second inaugural address in 2005 was as much of a ringing statement along this line as has come from any American president, and a stark contrast to what one hears from the autocrat-schmoozing Trump. “It is the policy of the United States,” Bush declared, “to seek and support the growth of democratic movements and institutions in every nation and culture, with the ultimate goal of ending tyranny in our world.”

Some have interpreted Bush’s posture as a scramble for a new justification for the Iraq War — which was encountering serious problems by inauguration day in 2005 — after a previous rationale involving weapons of mass destruction became discredited. That interpretation is unfair to Bush and understates how much democratization motivated the neocons who shaped so much of Bush’s foreign policy. Unconventional weapons and mythical alliances with a terrorist group were merely talking points seized on to sell a war that the neocons had long desired and hoped would trigger, through regime change in Baghdad, a bigger political change throughout the Middle East.

If Trump wins a second term, one can expect no more democracy promotion than in his first term, which is to say none. A Biden presidency probably would be friendlier to policies aimed at fostering democracy abroad. But the huge damage-repair tasks Biden would face, and the attention and political capital those tasks would require, leave little room for anything resembling a serious democracy-promoting program as a major foreign policy priority. In any event, coming out of the 2020 election year the democracy that most will need nurturing is America’s own.

Democracy at home and abroad

There is an important connection, however, between democracy at home and democracy overseas. That connection surfaced in debates near the end of the nineteenth century, as the United States was first flexing its global muscles. People on both sides of that debate were American exceptionalists who believed that the United States had something special to offer in promoting democracy in the world, but differed on how that special something ought to be used. One school of thought emphasized America’s role as a brilliant exemplar of liberty and democracy that can inspire other nations to move in the same direction. The other school, which came to dominate insofar as the United States became an imperial power with its war against Spain in 1898, believed that U.S. power should be used more directly to achieve political change abroad.

The mess that Bush and the neocons created in Iraq constitutes a strong argument against the direct-action school and in favor of the one about setting an example. In the simplest terms, the mistake the neocons made was to believe that democracy can be injected through the barrel of a gun. More broadly, their mistake concerned their faith in regime change — a subject on which Trump’s administration, insofar as its favorite bête noire Iran is concerned, represents another point of continuity with the neocons.

That faith mistakenly believes that a wide variety of evils and dysfunction can be cured by toppling incumbent rulers. It disregards the conditions needed for stable democracy, the disadvantages for any system that is imposed from outside, and the possibility that a change of regime can be a change for the worse and not necessarily for the better. The false promise of regime change has entailed other messes besides Iraq, especially in the Middle East.

A large part of the answer to the question of what happened to democracy promotion is thus that the neocons led it into a destructive and discredited dead end. But despite the discrediting, the faith still has believers, as the current administration’s posture demonstrates.

There is room for direct action, of a more modest sort, to encourage greater democracy abroad. The organizations having that mission that are associated with American political parties — the National Democratic Institute and International Republican Institute — provide useful ground-level, practical assistance in the mechanics of electoral politics. The U.S. government, while refraining from trying to force-feed democracy, can do much to encourage observance of the sorts of human and political rights that are necessary precursors to the emergence of liberal democracy, as Daniel Brumberg has proposed for the next administration’s policy toward the Middle East.

But underlying anything the United States does in the way of encouraging democracy in other nations must be a putting of its own democratic house in order. Happily, the domestic and foreign policy requirements all point in the same direction. What Americans need for the health of their own polity is also what is needed to inspire others overseas.

The exemplar principle involved has a long and noble history in America. John Winthrop saw his Massachusetts Bay colony as a “city on a hill” that would be a shining example to the rest of the world. Three and a half centuries later, Ronald Reagan repeatedly invoked Winthrop’s imagery to describe a modern and powerful United States.

First principles of democracy

The time is ripe for explicit discussion in the United States of fundamental principles of democracy. One of the two major political parties has been straying ever farther from support for democracy at home, evidently out of a belief that as a minority without the support of most citizens it will be consigned to opposition if a free vote by all citizens determines who is in power. Most of the time this belief hides behind voter suppression efforts rationalized with accusations of voter fraud.

But recently Senator Mike Lee (R-Utah) made an anti-democratic posture open and explicit. Lee tweeted, “The word ‘democracy’ appears nowhere in the Constitution, perhaps because our form of government is not a democracy. It’s a constitutional republic. To me it matters. It should matter to anyone who worries about the excessive accumulation of power in the hands of the few.”

Lee is treating concepts such as “democracy” and “republic” as if they were mutually exclusive, which they are not. The alternative to a republic is not democracy; it’s a monarchy. Monarchies can be highly democratic (e.g., Denmark) or highly autocratic (e.g., Saudi Arabia). Similarly, states with a non-royal head of state and calling themselves republics range from the democratic (e.g., Germany) to the autocratic (e.g., Egypt).

Americans should indeed worry about “excessive accumulation of power in the hands of the few,” but that worry does not lessen — instead it increases — when that power is bestowed not through a democratic procedure involving all citizens voting freely but instead by some undemocratic procedure favoring a minority. The answer to excessive accumulation of power is a system of checks and balances and guarantees for minority rights amid majority rule, not the trashing of democracy. Thoughtful people from both Republican and Democratic administrations have been offering useful ideas for improvement in that regard.

Democratic theory constitutes a whole sub-discipline of political theory, and thinkers through the centuries have offered a variety of arguments in favor of democracy. But the most fundamental principle involved is quite simple. Those with power should rule in the interests of the governed. The best assurance that power will be exercised in this way is to for the governed to choose their rulers, and to be able to throw rulers out of office when power is not so exercised. No other type of political order comes close to providing that assurance.