Amid the ongoing global crisis caused by COVID-19, a new report from the European Council on Foreign Relations has troubling implications for the much-vaunted transatlantic alliance.

The report, released June 29, shows that the present crisis has brought European trust in the United States to an all-time low. In several European countries, including Denmark, Portugal, and Germany, two-thirds or more of respondents said that their views of the U.S. had worsened during the pandemic; in Germany, 65 percent, in Portugal, 70 percent, and in Denmark, 71 percent. Even in Poland, a country generally more sympathetic to the U.S. under Donald Trump, 38 percent said their view had worsened, while only 13 percent said it had improved.

Similarly, in no country did the percentage of respondents who said the U.S. had been their “greatest ally” during the crisis exceed the mid-single digits. In Germany, France, Spain, and Sweden, it was a dismal 1 percent, in Poland, 4 percent, and in Italy — which gave the U.S. its highest marks — 6 percent.

This data caps off several years of decline in European — and particularly Western European — perceptions of the United States in the Trump era. While the survey does not break down respondents’ reasoning for their change of views, the Trump administration’s abysmal handling of coronavirus both at home and abroad surely accounts for much of this shift.

Within the United States, the Trump administration has utterly failed to develop or implement a strategy for containing the pandemic on a national level. It was slow to support lockdowns, and slow to marshal resources for producing more medical equipment and PPE, while the president himself has proffered dangerous misinformation about the disease and has, through muddled messaging, actively discouraged mask-wearing and social distancing.

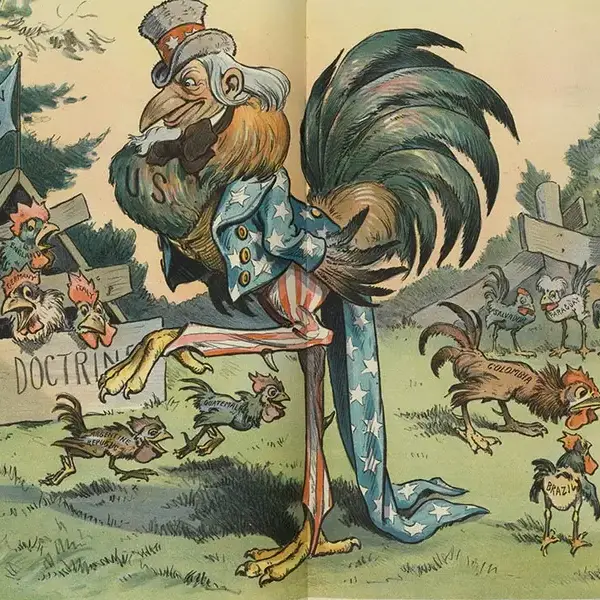

Internationally, the Trump administration has adopted a downright thuggish “every man for himself” approach to the pandemic. The administration has put more effort into casting blame on China and the World Health Organization — even attempting to pull funding from the latter — than to coordinating an international response to the pandemic. Even more egregiously, the Trump administration has been accused of seizing or diverting shipments of masks and other medical equipment bound for countries including Germany and several Caribbean nations.

It is no surprise, then, that such a vanishingly small number of Europeans see the United States as an ally in the fight against COVID-19.

It is worth noting that predictions that the pandemic would herald a new China-led world order appear premature, at least from a European standpoint, as the ECFR’s report shows that European perceptions of China have also worsened significantly during this crisis — even in Italy, where 25 percent say that China has been a key ally in addressing the pandemic.

Optimistic transatlanticists may take comfort in knowing that European views of the United States have plunged severely before — notably in the final years of the George W. Bush administration, due the Iraq war and Great Recession — only to recover under a new administration. But it’s worth asking whether Europeans will be so forgiving in the future. After at least two decades of such flagrant conduct abroad, Europeans may be less willing to separate their views of U.S. presidents from their views of the country itself.

In light of this, supporters of a strong U.S.-European relationship should be mindful of the problems with this alliance beyond Trump, which have become more apparent in the context of the global pandemic.

Despite Trump’s rhetoric, his administration has kept the structure of the transatlantic military alliance basically intact. Even with its latest controversial move to pull U.S. troops from Germany, the administration has chosen to relocate them to Poland rather than withdraw them entirely. Yet the Coronavirus pandemic has revealed the essential outdatedness of this structure in a world in which the existential threats the United States and Europe hold in common are largely non-military in nature — most notably, climate change and pandemic disease.

In the face of threats like these, the Cold War military alliance has served little purpose. It need not be scrapped entirely, but the U.S.-European relationship at a minimum should be restructured to center mutual cooperation against pandemics, climate change, and their secondary effects. The ECFR’s report suggests that such a change would be welcomed by Europeans, who during this crisis have become more supportive of both strengthening European institutions and of international efforts to address climate change.

The Trump administration and the COVID-19 pandemic have exposed deep fissures in the transatlantic alliance. It is probable that, should Trump lose the presidential election this fall, his likely successor Joe Biden will bring a rebound in global attitudes toward the U.S. simply by not being Trump. But his administration should not see this as an invite to return to the status quo. Deeper problems in the U.S.-European relationship, and in U.S. foreign policy more broadly, must be addressed, or we may well find ourselves in the same place a decade from now.