The indefensible death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police officers and the indiscriminate police violence in subsequent protests have returned police misconduct to the center of our national conversation.

It is not a conversation we may quickly or easily conclude. The problems in American policing are multitude and systemic, matters of both policy and culture. Much of this can only be corrected at the state or local level, and as there are around 18,000 law enforcement agencies in the United States, this is a monumental task. In very few cases could sweeping federal action affect any substantive reform

But one way in which Washington is directly implicated in police brutality is its contribution to the militarization of local police departments through the Pentagon’s 1033 Program and the so-called “war on terror” more broadly. Often in concert with the war on drugs, the fight against terrorism has been used to blur the lines between the military and the police, arming ostensible peace officers with mindsets, tactics, and weapons of war.

Many Americans first learned of the 1033 Program in 2014, when both peaceful protest and destructive unrest broke out in Ferguson, Missouri, following the fatal police shooting of Michael Brown. Photos from Ferguson showed police rolling through suburban streets in armored vehicles which, to the civilian eye, looked like tanks in a war zone. They looked like military gear because they were military gear — Defense Department castoffs given to local police departments for counter-drug and counter-terror operations.

The 1033 Program provides much more than vehicles. Police can also request weapons including bayonets, automatic rifles, and grenade launchers, as well as ammunition, body armor, robots, watercraft, and aircraft including surveillance drones. Former President Obama placed a few limits on the equipment transfers in 2015; Present Trump has since lifted them.

The outcome was predictable: Police never felt constrained by the Pentagon’s suggestion for how its hand-me-downs should be used. Cops use military gear when responding even to nonviolent protests, as we’ve seen yet again this past week. They use it in many more mundane situations, too.

Heavily armed SWAT teams, originally created for barricade and hostage situations, are widely employed beyond that intended purpose. Documented uses include arresting an unarmed optometrist for privately betting on football games, ransacking a backyard chicken coop, preventing unlicensed barbering, and forestalling a suicide attempt by preemptively killing the suicidal man.

Armored vehicles are used to patrol beaches, malls, theme parks, and college ball games. The St. Louis County Police Department, which includes Ferguson in its purview, uses a SWAT team to execute all search warrants. It is not unique in that practice. Escalation and threat inflation have become routine in American policing as they are in American foreign policy.

The 1033 Program, which predates post-9/11 counterterror efforts, is not the only way the our endless wars has fostered police militarization in America. Two other aspects deserve special attention.

First, less visible than armored vehicles is the civil liberties threat posed by the militarization of police intelligence collection and use. The “war on terror” served as justification for a massive expansion of domestic surveillance in America, and that expansion has trickled down from Washington to police departments around the country. Federal agencies share the data they collect via warrantless mass surveillance with state and local law enforcement. This spying is used to investigate suspected crimes with no connection to terrorism.

It’s also used to spy on people not suspected of any crime at all: Washington “loosened or ignored law enforcement guidelines restricting intelligence gathering [by] removing or weakening the criminal predicates necessary to ensure a proper focus on illegal activity,” a Brennan Center report explains. That produced “increased police spying on minorities and political dissidents and increased efforts to escape judicial and public oversight.” Meanwhile, federal funds buy police departments ever more invasive spying technology, including Stingray cell-site simulators whose use is actively concealed from the public.

Beyond the gear and surveillance, however, perhaps the most damaging effect of war on terror-encouraged police militarization is psychological. It pushes police officers engaging with the public to behave as they look, to act like soldiers dealing with enemy combatants. The task conforms to the tools provided — with deadly result.

“Give a man access to drones, tanks, and body armor, and he’ll reasonably think that his job isn’t simply to maintain peace, but to eradicate danger,” observed The Concourse writer Greg Howard amid the Ferguson demonstrations in 2014. “If officers are soldiers, it follows that the neighborhoods they patrol are battlefields. And if they’re working battlefields, it follows that the population is the enemy.”

This dynamic is deliberate: Police officers are explicitly trained to conceive of themselves as warriors in battle, always on high alert and prepared to kill. And it is disproportionately true in black and other minority communities, as the deaths of Floyd and Brown — and Breonna Taylor and Atatiana Jefferson and Philando Castile and Walter Scott and Tamir Rice and Aiyana Jones and so many more — steadily remind us. As long as police continue to function as an occupying military force, that list will continue to grow.

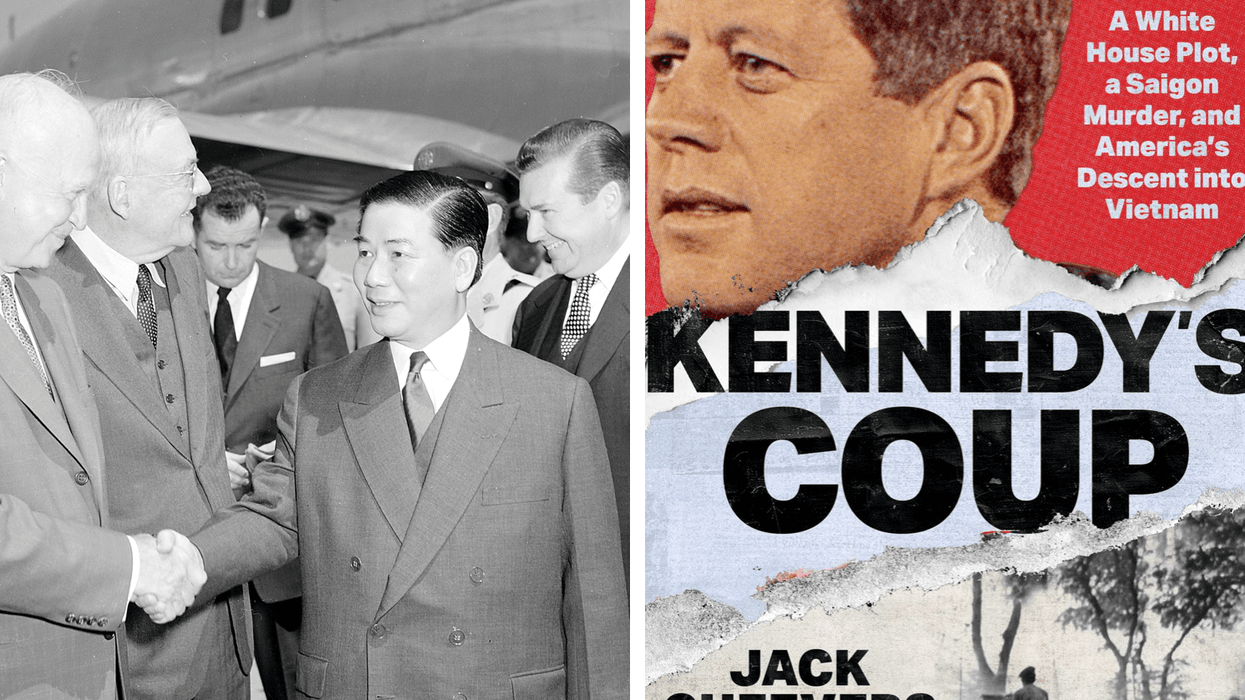

President John F. Kennedy and Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. in 1961. (Robert Knudsen/White House Photo)

President John F. Kennedy and Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. in 1961. (Robert Knudsen/White House Photo)