American leaders have never favored other countries getting nuclear weapons. It would be foolish to start now.

There is no secret to the atomic bomb. Its development “involved no new fundamental principles or concepts,” warned Manhattan Project scientists. “It consisted entirely in the application and extension of information which was known throughout the world.” They built the bomb with slide rules listening to Glenn Miller. All it takes to join the nuclear club today is sufficient political will and sufficient resources.

That is why U.S. leaders have always worked to stop its spread. It is not just about stopping the bad guys from getting the bomb; it has always fundamentally been about stopping the bomb itself.

President Harry Truman did not want the Soviet Union to get the bomb, but neither did he want Britain to have it. During World War II, the Americans kept the British partly in the dark about bomb design; after the war, Congress prohibited atomic information sharing. But this did not stop the Soviets from their first nuclear test in 1949, nor did it stop the British from theirs in 1950.

President Dwight Eisenhower was against the spread of the bomb, telling his National Security Council in 1954 that, “Soon even little countries will have a stockpile of these bombs, and then we will be in a mess.” Still, a determined France joined the nuclear club in 1960.

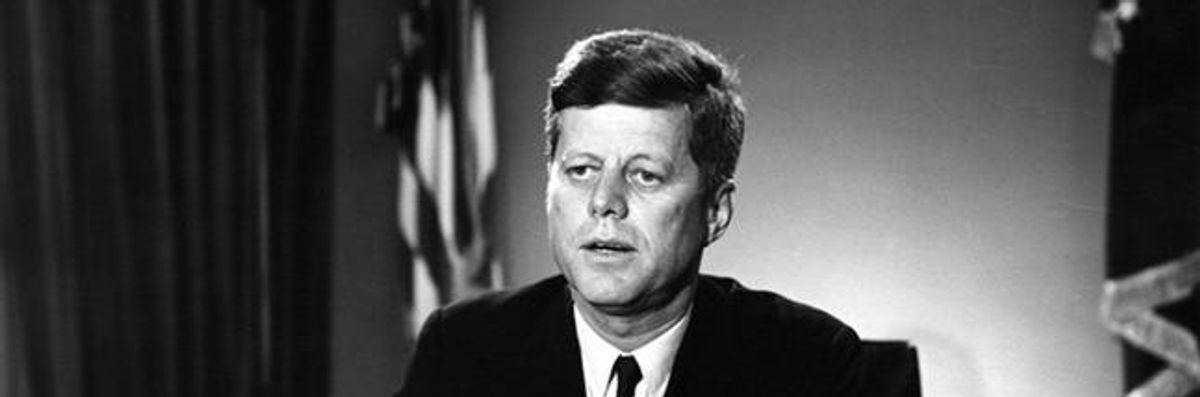

The fact that our allies had the bomb was of no comfort to President John F. Kennedy. In his third presidential debate with Richard Nixon in October 1960, Kennedy slammed Nixon and Eisenhower for not doing enough to end nuclear testing and stop the spread of the bomb, “There are indications, because of new inventions,” he said, “that ten, fifteen or twenty nations will have a nuclear capacity — including Red China — by the end of the presidential office in 1964.”

It was not just our adversaries that worried Kennedy. A 1958 National Intelligence Estimate, which Kennedy had likely read as a U.S. Senator, warned of programs in 16 countries, including Sweden, Norway, Switzerland, West Germany, Canada, Japan, India, and Israel. It was not in U.S. interests for any of these countries to get the bomb.

When Kennedy negotiated and signed the Limited Test Ban Treaty in 1963, banning nuclear tests in the atmosphere, outer space, and underwater, he saw the inherent link between nuclear disarmament and nuclear proliferation. His treaty was a step towards ending the arms race and stopping the spread of the deadliest weapon humankind had ever invented.

“I ask you to stop and think for a moment what it would mean to have nuclear weapons in so many hands, in the hands of countries large and small, stable and unstable, responsible and irresponsible, scattered throughout the world,” Kennedy said in an address about the treaty. “There would be no rest for anyone then, no stability, no real security, and no chance of effective disarmament. There would only be the increased chance of accidental war, and an increased necessity for the great powers to involve themselves in what otherwise would be local conflicts.”

That is why he opposed West German atomic intentions and threatened to “haul out” of Europe in 1962 — effectively ending American participation in NATO — if Bonn moved forward with a nuclear weapons program. (Ironically, Trump now threatens to haul out of Europe if Germany doesn’t move forward with a nuclear program, in this case, buying new nuclear-capable jets to “continuously invest in NATO’s nuclear participation.”)

This American policy was not limited to liberal Democrats or to our European allies. Henry Kissinger told President Richard Nixon in 1969 that Israeli nuclear weapons would “not be in our interest.” Later on, Kissinger — working for President Gerald Ford — outlined U.S. policy towards South Korea in 1974 as inhibiting “to the fullest extent any ROK development of a nuclear explosive.” In 1982, President Ronald Reagan warned Pakistani leader General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq that Islamabad’s pursuit of a bomb “threatened seriously to damage relations between the United States and Pakistan,” despite U.S. reliance on the latter as a staging base during the Soviet-Afghan War.

Again and again, successive U.S. presidents of both parties have been faced with the prospect of friendly proliferation. Again and again, they rejected it, though clearly, not strong enough.

It is tempting to think that it would be cheaper and more effective to have distant allies like Germany or South Korea or Saudi Arabia get the bomb rather than link their security to U.S. forces, bases, and assurances. Nuclear theorists like Kenneth Waltz point to the so-called “pacifying” effects of nuclear weapons, saying their existence makes states “exceedingly cautious” and therefore less likely to fight similarly-armed opponents. If more countries had the bomb, the logic goes, fewer wars would occur.

But countries do not obtain the bomb in a vacuum. The nuclear posture and strategic decisions of nuclear-armed nations have a significant, often immediate, impact on the nuclear acquisition decisions of other nations. More simply: If your adversary or your neighbor goes nuclear, you will, too.

There is nothing automatic about the nuclear domino theory, and it has been successfully countered in some regions, but the theory is generally correct. The Soviet Union got the bomb because, as Stalin told his scientists after Hiroshima, “The balance has been broken. Build the bomb. It will remove the great danger from us.” Britain and France got the bomb because the Soviets (and the U.S.) had it. China did the same, then India got the bomb because China did; Pakistan because India did.

Nuclear competition in Asia would not end if South Korea decided to build a nuclear arsenal. Others in the region would likely follow suit. Japan, Taiwan, perhaps Vietnam. Similarly, a Saudi bomb would likely beget an Iranian bomb, a Turkish bomb and even an Egyptian bomb. Far from making the region — and the United States — safer, these arms races would blanket the globe with nuclear tripwires, each primed to unleash unprecedented destruction at the slightest twitch.

Where you stand determines what you see. Kennedy and the other presidents stood atop the chain of command, and their own experiences with that awful responsibility (particularly with the near-miss of the Cuban Missile Crisis) colored how they saw nuclear politics. They recognized the limitations of theory in a world characterized by imperfect information and the frictions of human interaction. They understood what the nuclear theorists could not — that more countries having nuclear weapons would only increase the risk of their use, not lessen it.

Three months before the Cuban Crisis, Kennedy’s Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara, gave a speech in Ann Arbor, Michigan where he laid out this danger. “The mere fact that no nation could rationally take steps leading to nuclear war does not guarantee that a nuclear war cannot take place,” he said. “Not only do nations sometimes act in ways that are hard to explain on a rational basis, but even when acting in a ‘rational’ way they sometimes, indeed disturbingly often, act on the basis of misunderstandings of the true facts of a situation. They misjudge the way others will react, and the way others will interpret what they are doing.”

Any attempt to rationalize nuclear relationships — treating adversaries like two sides of a balanced equation — removes the human factor: the tendency towards irrationality and error. In a world with just a handful of nuclear states, that factor has already nearly led to apocalypse. In a world with a dozen more, those risks would go up exponentially.

It does not have to be this way. For over 50 years, since the signing of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, successful diplomacy, security assurances, and global norms have largely kept nuclear proliferation at bay. The nightmare scenario of dozens of nuclear states has so far been averted, in no small part through the conscious and continual effort of American presidential administrations of both parties. Yes, there will always be those who advocate for more nuclear weapons in more hands. But the forces of restraint, and with it, survival, have prevailed and can continue to prevail if U.S. policy leads the way.

That is the beauty of nuclear policy: it leaves a track record. We can look back over the 75 years of the nuclear age and see what has worked to make the world safer and what has made it more dangerous.

When we let the nuclear virus spread unchecked, without any mitigation or suppression efforts, the contagion went from one nuclear nation in 1945 to five by 1964. From two bombs to over 34,000. But when we applied controls like test ban treaties, strategic arms limitations, nuclear non-proliferation accords and, most importantly, reduction treaties, we were able to flatten the nuclear curve, to limit the spread to just the nine nations today and to slash arsenals by over 85 percent from their peak of some 66,000 weapons in the mid-1980s to just under 13,400 today.

The Trump administration rejected this proven treatment plan. They resurrected 1950’s policies, dubbed them “new thinking” and “next generation arms control” and systematically destroyed the strong containment and suppression techniques patiently constructed by their predecessors.

The results are not the promised “better deals.” Reductions have stopped. Negotiations have stopped. Effective restraints, like the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action that shrunk Iran’s civilian nuclear program to a fraction of its former size, froze it for a generation and put it under lock and camera, have been abandoned without replacement. All of the nine nuclear nations are building new weapons. Capitals and columns buzz with talk of new national arsenals. Once again, some define the problem not as the weapons themselves, but as just the bad guys who have them.

We are at a nuclear tipping point. Continuing on this path leads to the nuclear nightmares of the 1960s. Change course and we can again live in a world with fewer weapons and fewer nuclear-armed states — one working steadily towards the elimination of the only weapon that can destroy humanity in an afternoon.

We should not be diverted by the illusion of nuclear stability. There is no such thing.