When I was in Seoul last month, the city buzzed with anti-government protests. Left-leaning citizens beat drums and blew whistles, while labor leaders and civil society activists screamed through megaphones for the impeachment of South Korean President Suk-yeol Yoon. Those rallies continued weekly, becoming larger and larger, ever more boisterous.

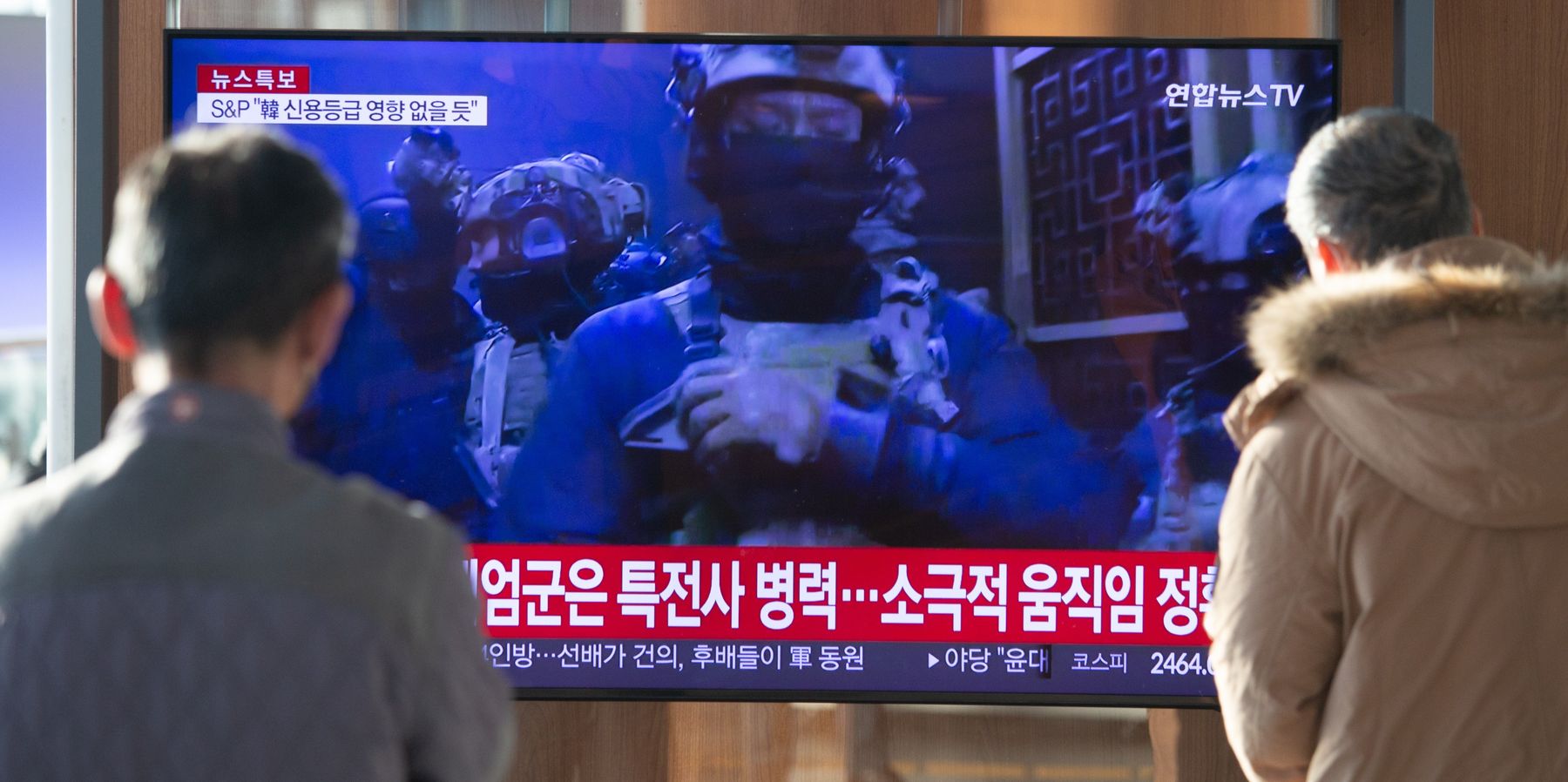

Then, on Tuesday night, Yoon struck back, declaring martial law and mobilizing the armed forces — until even louder citizen protests, a vote by the opposition-controlled National Assembly, and a rebuke from his own People Power Party (PPP) forced the right-wing president to back down.

Although it was once a brutally repressive military dictatorship, South Korea has been viewed as a model democracy for almost 40 years. So Yoon’s effort to reinstall authoritarian rule was shocking — but maybe not surprising.

There are at least two ways to understand what happened here: a more superficial story that revolves around the government’s policies and behavior; and a deeper story that has to do with Korea’s competing nationalisms.

Superficially, we know that Yoon was desperate. Elected by a paper-thin plurality in May 2022, he has been assailed almost from the start by critics of his domestic and foreign policy. In Trumpian style, he campaigned as a critic of feminism, which he blamed for Korea’s low birthrate, and vowed to abolish the Ministry of Gender Equality. He pushed to increase the lid on weekly working hours, which upset labor unions. And he took various steps to reconcile with Japan, which had colonized the Korean peninsula from 1910 to 1945, even offering private funds to compensate Koreans forced to work in a Japanese mine during World War II.

The president also found himself embroiled in scandals, most of them associated with his wife. The opposition Democratic Party accused the First Lady of manipulating stock prices for personal gain, and then highlighted a video — captured on a left-wing YouTube channel — that appeared to show her accepting a luxury handbag as a gift. A member of the ruling PPP even compared the First Lady to Marie Antoinette.

Yoon’s popularity plummeted, and his party — already in the minority in the unicameral legislative body — lost even more seats in April’s elections. His policy agenda stalled, leaving him able to do little more than veto progressive legislation passed by Democrats.

Last month, the president went on national TV to apologize for his wife’s alleged indiscretions, promising to establish an oversight office. But he nixed calls for a wider investigation, triggering more protests. In November, when I was in Seoul, Yoon’s favorability rating had dropped to a diminutive 17 percent.

Justifying his decision to use the military to block all “political activity,” Yoon told Koreans he was acting to protect the country from “communist forces,” whom he also described as "despicable pro-North Korean anti-state forces.” This statement hints at the deeper story about the country’s competing nationalisms.

At the end of World War II, U.S. forces occupied the southern half of the Korean peninsula and Soviet forces occupied the north, ending Japanese colonial rule. Author Bruce Cumings shows how a Cold War accommodation produced two countries in 1948: a pro-capitalist, U.S.-backed South Korea and a pro-communist, Soviet-backed North Korea. The two new countries fought a bitter war that ended exactly where it started — at the 38th parallel.

For most of its early life, South Korea was ruled by military generals with the ardent support of powerful business executives and the U.S. government. The authoritarian government imprisoned and murdered labor and student activists pushing for democracy. It invoked a nationalism based on fear of Pyongyang, which had invaded in 1950 and continued to agitate for violent unification, planting bombs, staging terrorist attacks and kidnapping South Koreans.

The pro-democracy movement, which finally prevailed in 1987, also invoked nationalism — but a very different kind. It viewed North Koreans as brothers and sisters led astray by geopolitics, not as implacable enemies. For this younger generation, the foe was a military-business elite that had collaborated in the past with Japan, the colonial master, and now conspired with the U.S., a post- (or maybe neo-) colonial master with 30,000 troops on Korean soil.

South Korea today is characterized by what Hur and Yeo call “nationalist polarization,” where political “parties are divided on mutually exclusive visions of the nation.” They describe two illiberal outcomes. First, this highly charged form of polarization leads to a zero-sum competition that encourages the winning party to run roughshod over process and rights in the name of national security, while packing agencies and courts with actors who share nationalist goals. Second, it transforms the opposition into an “existential threat” to the nation, rather than merely a misguided competitor.

We have seen plenty of this kind of illiberal behavior in South Korea over the past decade. Former president Geun-hye Park, the daughter of Gen. Chung-hee Park, Korea’s first military dictator, invoked the National Security Law to ban a left-wing party viewed as pro-North. The conservative president also denied state support to hundreds of artists and cultural organizations blacklisted for criticizing her administration.

Park’s progressive successor, Moon Jae-in, set up 39 special committees to investigate bureaucrats suspected of violating the Left’s nationalist agenda by, for example, cooperating too much with Japan or cracking down too hard on North Korea. Another investigation led to the conviction of a former conservative president on charges of corruption. Moon also used his power to stifle civil society organizations engaged in anti-Pyongyang activities, and barred a cable TV show from airing a speech by a North Korean defector.

Far from defending President Yoon’s short-lived imposition of martial law, I am trying to explain it in the context of competing nationalisms. He viewed the Left as a threat to the Right’s vision of national identity and security, just as the opposition viewed him as a fundamental threat to their vision. This zero-sum confrontation led to the current crisis, and does not bode well for Korea’s future.

- The shortsighted US-Japan-South Korea military pact ›

- Fearing his enemies, South Korea's Yoon declares martial law ›

- Is the US-S. Korea alliance still 'ironclad'? Should it be? | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Coup and impeachment boost liberal in South Korea election | Responsible Statecraft ›