The United States is “prepared” to deploy troops to Haiti as part of a multinational effort if the crisis in the country worsens, though officials are not actively considering such a move, according to the U.S. military commander for Latin America and the Caribbean.

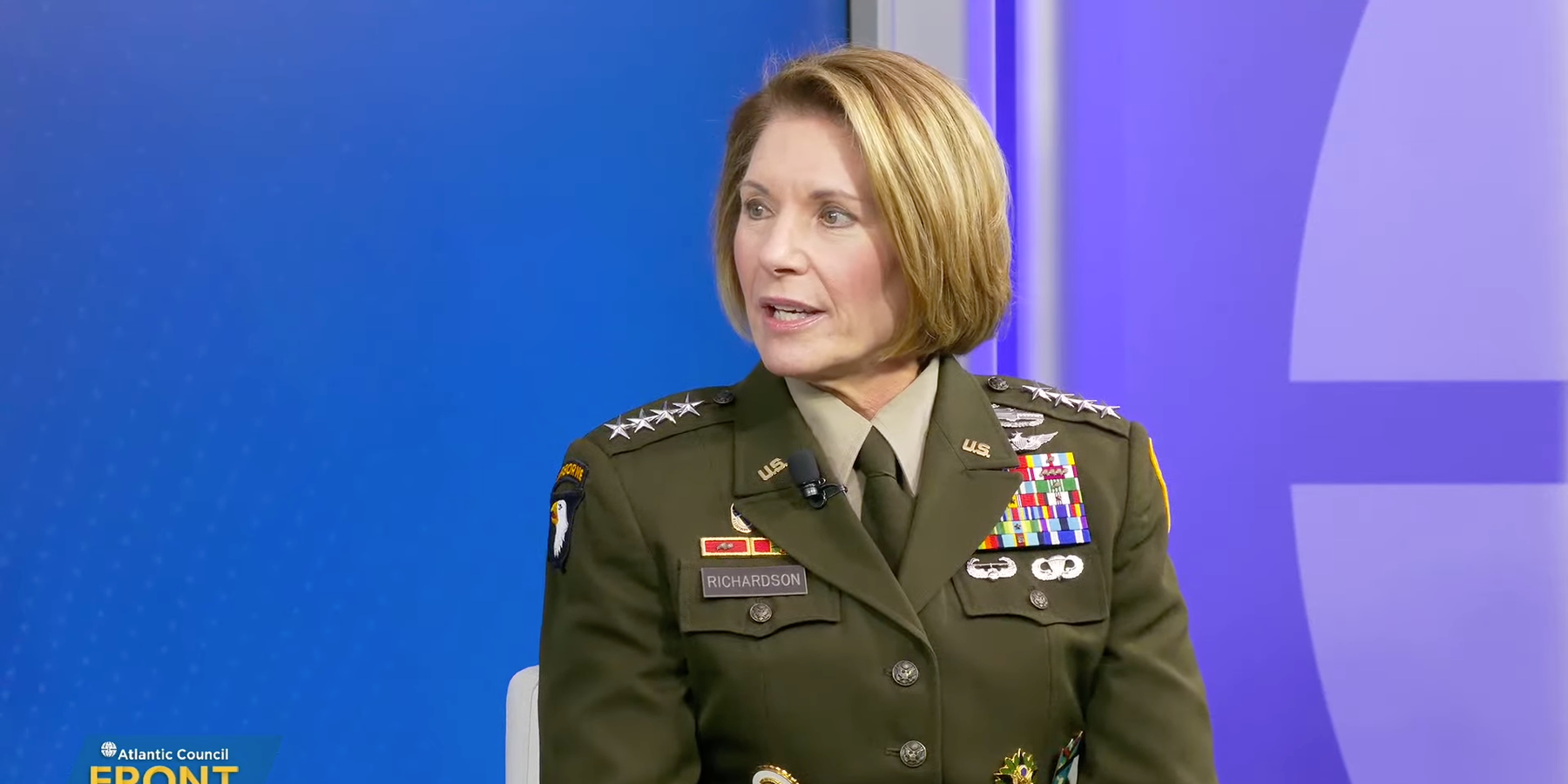

“We wouldn’t discount” that U.S. troops could be involved in an international effort in Haiti, said Gen. Laura Richardson, commander of U.S. Southern Command, during a Tuesday event at the Atlantic Council. “We are prepared if called upon by our State Department and Department of Defense,” Richardson added, noting that she doesn’t envision a “U.S.-only solution” to the deteriorating situation.

The top general’s comments highlight the extent of Haiti’s current crisis, in which the government has all but fallen apart in the face of armed groups that are now preventing Ariel Henry — the country’s internationally recognized leader — from returning from an overseas trip. Pentagon officials are now considering using Guantanamo Bay to hold Haitian refugees if the situation deteriorates further.

Henry, who took over as de facto president following the 2021 assassination of Jovenel Moïse, said recently that he will step down and hand power over to a transitional council made up of key stakeholders from Haitian civil society and political groups. There is, however, one controversial condition: Participants in the foreign-backed council must endorse an international intervention to restore security in Haiti.

A dueling transition effort, led by paramilitary-leader-turned-avowed-revolutionary Guy Philippe, has rejected the prospect of foreign intervention but is unlikely to earn support from Western leaders.

While U.S. officials continue to emphasize their support for a Kenyan-led (but U.S.-funded) United Nations intervention, they have carefully avoided suggesting that American soldiers could be directly involved in any military operations in the country. The Pentagon’s only recent operation in the country was a mission last week to airlift U.S. embassy staff out of Haiti.

Washington’s concerns about direct intervention are in part due to the long history of U.S. interference in Haitian politics, including a decades-long U.S. occupation in the early 1900s and alleged American interference in several recent Haitian elections. Many in Haiti see the U.S. as partially responsible for the current crisis due to American support for Henry and other Haitian leaders who have crushed protests and steered the country toward authoritarian rule.

But the UN mission has hit its fair share of snags, with Kenyan courts blocking the country’s involvement in the intervention over constitutional concerns. In fact, Henry only left the country in order to sign a revised agreement with Kenyan officials before learning that he would not be able to make the trip home. If the UN intervention does come together, U.S. soldiers will provide logistical and sustainment support for Kenya’s operations, according to Richardson.

Other obstacles also stand in the way of the Kenya operation, according to Jake Johnston, a senior research associate at the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR). Even if Kenyan courts sign off on the operation, Johnston says it’s not clear how Kenyan forces could even land in Port-au-Prince given the level of insecurity. And the level of violence required to defeat the gangs by force would risk “ridiculously high” civilian harm in populous areas.

As the Kenyan-led mission hangs in the balance, the situation continues to deteriorate. “The idea of foreign troops, it's basically served as an excuse to not do anything to address the situation on the ground,” Johnston said. “For a year and a half, we've been debating how this is going to happen, who's going to fund it, who's going to lead it, what they're going to do.”

While the government continues to function in limited ways, local armed groups control large swathes of the capital city, and street violence has forced many Haitians to flee their homes. Food insecurity has also tripled since 2016, giving Haiti “one of the highest levels of hunger in the world,” according to the World Food Program.

Haiti watchers blame the crisis on years of corruption and weak governance, in addition to lax policies toward armed groups based in poor neighborhoods. Those paramilitary groups have had an uneasy relationship with Haitian officials, though their interests have at times aligned, as was the case in 2018 when armed groups stepped in to break up anti-government protests.

The current crisis began last month when disparate paramilitary groups declared that they had joined forces to oust Henry. It is unclear whether the groups have enough in common to remain unified in their anti-government efforts; the gangs carried out a similar effort last year that fizzled out after a few weeks, according to Johnston.

Now, the best path forward for foreign officials is to allow Haitians to solve the crisis with minimal foreign influence, Johnston argues. “A huge part of this crisis is a result of U.S. foreign policy, which propped up Henry despite every indication that this was going to blow up in their face,” he said. “You can't impose the government from an external source or power. It's not going to work in the long run, however much we might want it to.”

“We might not like what happens in a local process,” Johnston added, “but it’s not really up to us to make that choice.”

- No matter how well-intentioned, armed mission in Haiti is a mistake ›

- From coup to chaos: 20 years after the US ousted Haiti’s president ›

- Kenyan troops to arrive in Haiti amidst doubts over peacekeeping mission's viability | Responsible Statecraft ›