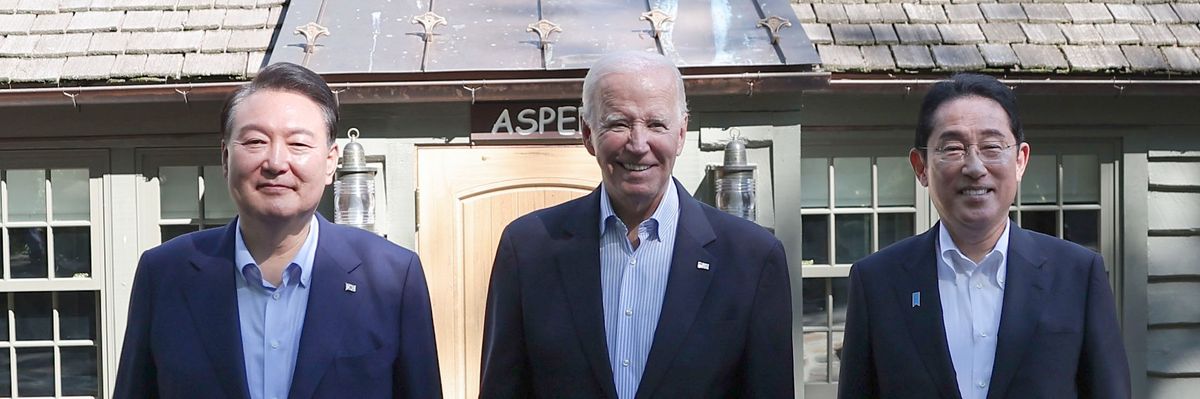

Driven by their common perception that North Korea and China posed growing threats to their nations’ security, U.S. President Joe Biden, South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol, and Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida agreed at last August’s summit at Camp David to elevate trilateral military ties to an unprecedented level.

They have been demonstrating this commitment everyday since, some say to the detriment of stabilizing relations with Pyongyang and Beijing.

In recent years, North Korea has steadily expanded its nuclear arsenal and become more aggressive in its rhetoric and posturing. In light of Taiwan’s deepening resistance to the idea of eventual unification with mainland China, an impatient Beijing appears to be relying increasingly on displays of its increasing military might, too, as a way to demonstrate its own determination to bring the territory under its control, raising concerns that it may yet resort to force to achieve unification in the coming years.

Since the Camp David summit, Washington, Seoul, and Tokyo have worked to enhance their collective combat readiness, such as conducting regular joint naval and aerial maneuvers in regional maritime and air spaces, to strengthen deterrence and demonstrate their own opposition to North Korea and China.

Policymakers in the three capitals may believe that continuous reinforcement of trilateral military cooperation and posturing will act as a deterrent to aggressive behavior by Pyongyang and Beijing. However, such optimism may prove unfounded. The evolving Japan-U.S.-South Korea trilateral partnership might pose considerable risks because their approach to deterrence overlooks security dilemmas faced by North Korea and China. In a new Quincy Institute report, Mike Mochizuki and I examine this issue and offer recommendations to address it.

Insecurity about regime survival plays a decisive role in North Korea’s development of nuclear weapons and its strategic calculations as to whether and when to use them. An effective strategy to deal with North Korea would therefore seek to deter North Korea but, at the same time, to avoid fueling its anxiety about foreign efforts to engineer regime change or collapse.

Unfortunately, the current trilateral approach appears likely to exacerbate Pyongyang’s worst fears and insecurities in this regard.

In seeking to deter North Korea, Washington, Seoul, and increasingly Tokyo are relying on offensive military capabilities and doctrines to retaliate against possible North Korean aggression. Emphasizing offensive military functions can indeed bolster deterrence in many circumstances, but they may also overshadow their defensive intentions and thereby contribute to North Korea’s conviction that only stronger nuclear capabilities and more offensive nuclear posture and strategy can guarantee regime protection and survival.

As Pyongyang continues to make progress in its nuclear and missile development, U.S., South Korean, and Japanese policymakers may become tempted to respond with a more offensive collective military posture and bigger and more threatening joint exercises. Such a response, however, may exceed the basic requirements for deterrence and can thus fuel escalation dynamics, increasing the risks of actual conflict. In our report, we offer alternative suggestions to deter North Korea without undermining stability.

Regarding the Taiwan issue, Washington, Tokyo, and Seoul have now adopted an implicit yet firm trilateral stance against possible Chinese use of force to achieve unification, stating in their joint communique their strong opposition to unilateral attempts to change the status quo in the region. While the unambiguous trilateral opposition to unification by force can benefit deterrence, it needs to be coupled with efforts to credibly reassure China that the trilateral partnership will not try to promote Taiwan’s permanent separation.

In terms of reassuring China on the Taiwan issue, all three capitals are falling short so far, as they appear to have become increasingly indifferent to, or even ambivalent about, the importance of reaffirming their respective One China policies in recent years.

The ostensible U.S., Japanese, and South Korean reluctance to reaffirm their One China policies as clearly as they did in previous years risks feeding into Beijing’s suspicion that Washington is orchestrating a containment coalition to pursue a “One China, One Taiwan” policy. Such an interpretation of the trilateral partnership’s intent will likely be bolstered if Washington begins to accept the notion that Taiwan should be permanently kept separate from the mainland for the sake of U.S. regional military advantage.

U.S. policymakers may be tempted to involve Japan and South Korea in joint combat operational planning for a Taiwan contingency, but moving in that direction can make escalation and conflict more likely by compounding Bejing’s fears and fueling its resolve to reshape the status quo in its favor.

To decrease the risk of conflict over Taiwan, we suggest that Washington, Tokyo, and Seoul devote more attention to stabilizing relations with China through credible reassurances on the Taiwan issue. They should also pursue a defensive-denial approach to Taiwan contingency planning, which we explain more in our report.

The three countries should also be alert to the possibility that their transition into an overtly anti-China coalition may prompt Beijing to create a countervailing anti-U.S. military partnership with Russia and North Korea. China has so far maintained a relative distance from the tightening of military ties between Russia and North Korea that has taken place since the former’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Russia reportedly proposed China trilateral naval drills with North Korea last year. The fact that such drills have not yet taken place indicates that Beijing remains cautious about the idea of trilateral military cooperation with Moscow and Pyongyang.

Indeed, China has an interest in constructive engagement with the United States, Japan, and South Korea and likely prefers not to further jeopardize it by pursuing an outright military bloc formation with Russia and North Korea. However, its calculation may change if it comes to believe that the Japan-U.S.-South Korea partnership poses too serious a threat to its core interests, such as Taiwan and economic development. The recent call between President Biden and Xi Jinping suggested that Beijing views U.S.-led economic and technological restrictions as second only to the Taiwan issue as an area of concern with the potential for conflict.

With that in mind, Washington, Tokyo, and Seoul should tread carefully with their coordination of “de-risking” with China. U.S.-led “de-risking” risks going beyond simply seeking to reduce Chinese access to advanced technologies with clear military applications to the point of threatening China’s economy. Even while working together to tackle genuine economic challenges posed by China, such as coordinating responses to China’s economic coercion, the three countries should seek to promote inclusive economic and diplomatic engagement with Beijing to reassure it that they do not intend to create a broad exclusionary anti-China economic or technological bloc. We offer several ways to do this in our report.

U.S. policymakers should also keep in mind that President Yoon’s conservative policy preferences and philosophy have played a key role in enhancing trilateral military ties and cooperation. But what would happen if South Korean voters, in 2027, elect a liberal president who would be more sensitive to historical disputes with Japan and prefer a more congenial approach to North Korea and China? In such a case, trilateral cooperation centered on confronting North Korea and China may cease to be viable.

For the trilateral partnership to be more sustainable and synergetic, it should be oriented around reducing tensions and mitigating risks of conflict with China and North Korea. Such an approach would better serve U.S. interests by enhancing regional stability and allowing safer and more productive competition with China. It is also more likely to garner broader public support in both South Korea and Japan beyond the current political alignment between the two countries.

- Escaping the 'security dilemma' on the Korean Peninsula ›

- Is anyone else concerned that 'deterrence' isn't working with North Korea? ›

- US media ignored major anti-US military protest in South Korea ›

- It’s time to rethink US military ties with South Korea | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Can China, Japan, and South Korea just get along? | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Is China being played by North Korea and Russia? | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Competing 'nationalisms' led to shocking showdown in Seoul | Responsible Statecraft ›