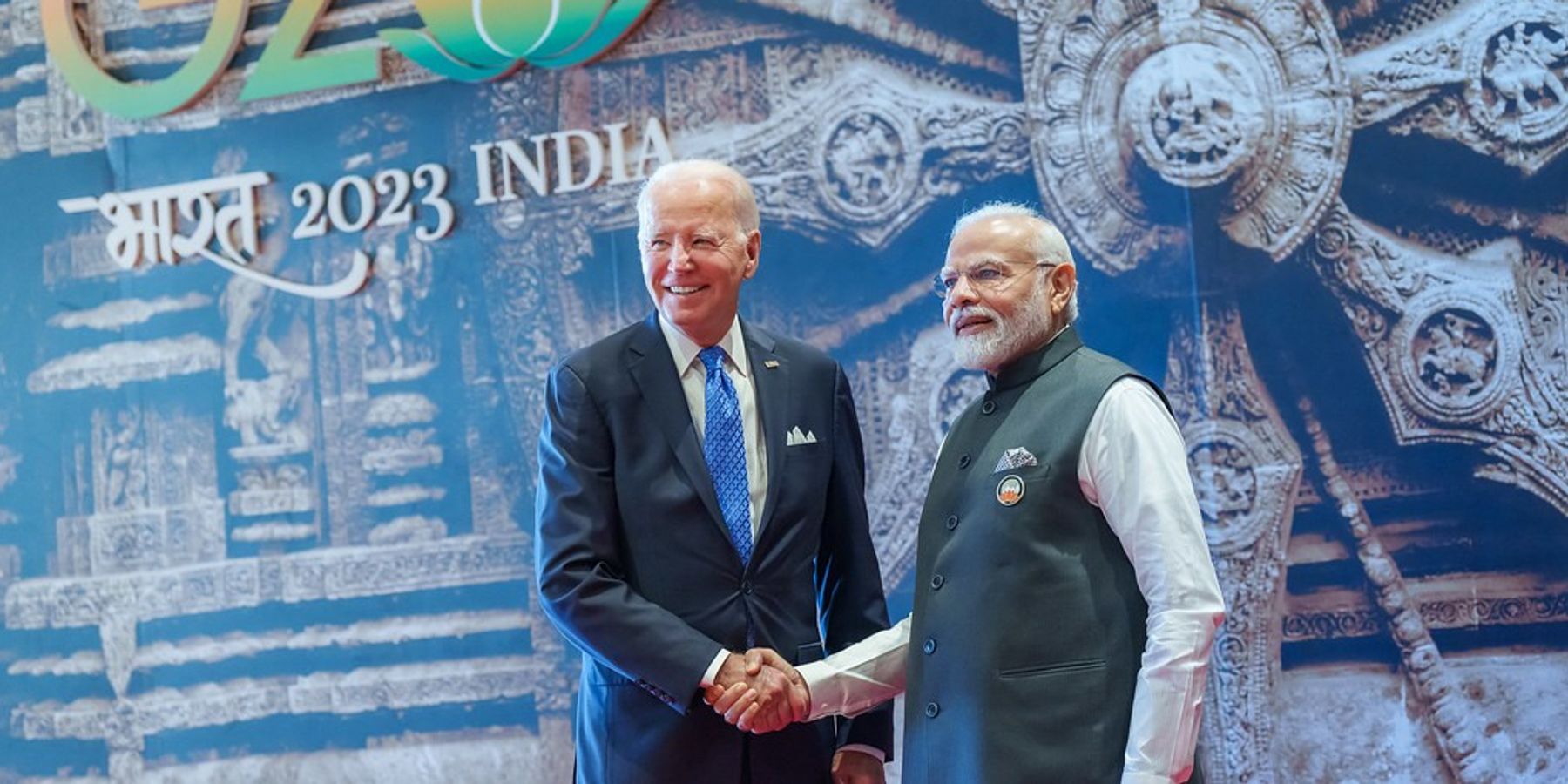

To many observers, the leadership of President Joe Biden and Prime Minister Narendra Modi has marked an emerging shift in the Indo-American relationship, pointing towards a new era of mutual alignment.

A plethora of bilateral summits proclaiming a “high-level of engagement” to craft “an enduring India-U.S. partnership,” expanded joint-defense collaboration, the 2+2 Ministerial Dialogues, deepening technological linkages, and shared security interests regarding the rise of China indicate there may have been a substantial shift in Indian strategy.

While relations are undeniably strong, policymakers should remain skeptical that this stems from an underlying geopolitical alignment. Despite moving closer to the Western camp, India maintains a strategy of multi-alignment and will likely continue to do so in the coming decades.

We Have Been Here Before

This is not the first time that there has been an apparent Indo-American rapprochement. India’s doctrine of nonalignment, combined with their linkages to the Soviet Union and American diplomatic relations with Pakistan, caused distrust throughout the Cold War. Yet, the partnership blossomed after the turn of the millennium under the Bush administration, with significant cooperation in counter-terrorism, advanced technological development, democracy promotion, and environmental protection.

Despite India’s nuclear program and subsequent nuclear tests violating the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), George W. Bush lifted economic and military sanctions in 2001. In 2006, India and the United States signed the Civil Nuclear Cooperation Agreement, which allowed access to civilian nuclear reactor technology.

Much like today, there were several joint agreements. If you file off the dates, many mirror Biden and Modi’s pledges, with commitments to expand joint exercises, defend democracy, and create cooperative groups such as the Defense Policy Group (DPG), which resulted in new American arms sales to India.

There was considerable optimism at the start of the Obama administration that India would officially pivot into the Western camp. However, this hope was illusory. New elections in India brought in elites who favored strategic autonomy. Obama inflamed fears around American credibility by improving relations with China and discussing a potential G-2, a core Indian concern. Despite inching closer towards alignment for the past decade, India rapidly flipped away from the United States by joining China-led initiatives such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, BRICS, and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. Furthermore, India continued to maintain its reliance on Russian arms, which limited the potential for joint military planning.

Obama tried to mend the rift, but it was too little, too late, and the alliance has maintained a distinctly transactional feel until the present day. A lesson should be learned: seemingly strong Indo-American bonds can crack when security interests shift.

Flashpoints for Tensions

Much like in the Obama administration, a confluence of factors could easily reverse recent gains. India and Russia remain partners despite the invasion of Ukraine. In line with much of the Global South, they have consistently abstained from condemning Russian actions and refused to sanction Russian oil (although allegedly this may have been in line with Washington’s desire to stabilize oil prices).

Perhaps most importantly, India’s military remains reliant on Russian arms. Recently, they started to somewhat distance themselves from the Russian defense industry, but India still calculates that a strong relationship with Moscow is necessary to prevent isolationism that would push them further into China’s strategic orbit.

This limits India’s commitment to one of the main American security architectures in the Indo-Pacific, the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD). Russian arms are not interoperable with the rest of the QUAD’s forces, which could dampen air and sea superiority in a crisis. But even if India tried to fully transition away from Russian arms, Russia has sold them the largest share of weapons for decades. The limited interoperability of Russian and American arms complicates any large-scale shift by magnifying costs and risking Indian defenses in the meantime. Regardless of how the American relationship develops, Russia will continue to be a fixture in Indian security interests for the foreseeable future.

India has new concerns about American reliability, especially after the withdrawal from Afghanistan. Already, there are concerns that the weapons left behind are arming Kashmir separatists trying to split from India in favor of Pakistan. While relations under the Trump administration were not hostile, a return to an ‘America First’ foreign policy could make India calculate they need to hedge their bets away from the United States if they don’t trust Trump’s willingness to assist in a crisis.

Perhaps the most recent flash point in the relationship was the attempted assassination against Sikh activist Gurpatwant Singh Pannun, an American citizen, on American soil. All signs point to Indian officials being directly involved with the plot, which could be unacceptable to the United States.

This points to a broader divergence between New Delhi and Washington: Indian democratic backsliding. It seems increasingly doubtful that Indo-American relations, as some have argued, can be grounded by shared ideological values. The rise of Hindu nationalism has tarnished Indian democracy, leading to discriminatory legislation against Muslim Indians and a substantial increase in hate crimes. Modi himself recently implied Muslims were “infiltrators,” a common Islamophobic trope in Hindu nationalist hate speech.

Outside extra-judicial killings, Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has increasingly escalated assaults against India’s democratic principles. Political opponents, from politicians to activists to journalists, have been jailed under the pretense of anti-corruption measures, with peaceful protests violently stamped out. Most measurements of democratization have downgraded democratic India’s status to “partly free” or even an “electoral autocracy.”

None of this is to gloss over the United States’ electoral flaws, but India’s trajectory is directly contradictory to the “shared values” expressed in the joint summits and implies that should security interests diverge, there won’t be much tethering Indo-American coordination.

Indian Multi-Alignment and Great Power Ambitions

It is undeniable that Modi’s foreign policy choices are motivated by great power desires. India is the world’s most populous country and in a position to surge economically. A consumer boom and wage growth are likely incoming, with plenty of room for industries to meet the needs of the growing consumer class. Its population size will create a powerhouse working class to power growing markets for emerging technologies, clean energy, and businesses seeking new supply chains outside of China.

Additionally, India is increasingly trying to position itself as the voice of the Global South, which often puts it in opposition to American and European interests. India has one of the strongest militaries in Asia and the ability to project power regionally. The Indian Ocean’s name is no coincidence. India will not give up regional hegemony without a fight.

To achieve these goals, India cannot play second fiddle to America forever. It is increasingly clear that India’s strategic approach is to keep its options open so it can take advantage of whatever side best suits its interests.

This is not to imply that there will be an imminent breakup. For the time being, there is a growing bipartisan understanding in Washington that China is the largest long-term threat to American security, which makes for a natural partnership with India, which fears Chinese territorial encroachment. India’s threat perceptions seem to be locked in after military crises in 2014, 2017, 2020, and 2022.

As of now, the BJP is positioned to maintain power after the 2024 election, making it unlikely to impact the trajectory of the relationship barring an unforeseen anti-American faction gaining footing. Should the party expand its hold over Parliament, the surface of the relationship may remain the same, but centralizing Modi’s power would only exacerbate his authoritarian and hawkish leanings.

Still, India’s growing illiberalism shouldn’t be a barrier for the moment. The United States has a long history of working with dictatorships that have questionable human rights records. Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Pinochet-controlled Chile immediately come to mind. Security interests frequently trump moral qualms.

But should the security situation change — as a result of U.S.-China rapprochement, a surprise change in Indian or American leadership, or a crisis of credibility — policymakers may find that there is not much at the core of the relationship. India may be useful to American strategists who want to balance China for now, but make no mistake, India will not sacrifice its core interests to appease the United States. Security relationships can seem momentarily strong, but they are a house of cards vulnerable to shifting geopolitical winds.

- India’s parlays with Russia point to middle power pushback on Ukraine ›

- US-India ties look rosy, but beware of over-militarization ›

- Modi’s setback will have little impact on India’s Foreign Policy | Responsible Statecraft ›

- How far can a Putin-Modi hug go? | Responsible Statecraft ›

- The India-Pakistan Clash: Welcome to the Post-Unipolar World | Responsible Statecraft ›