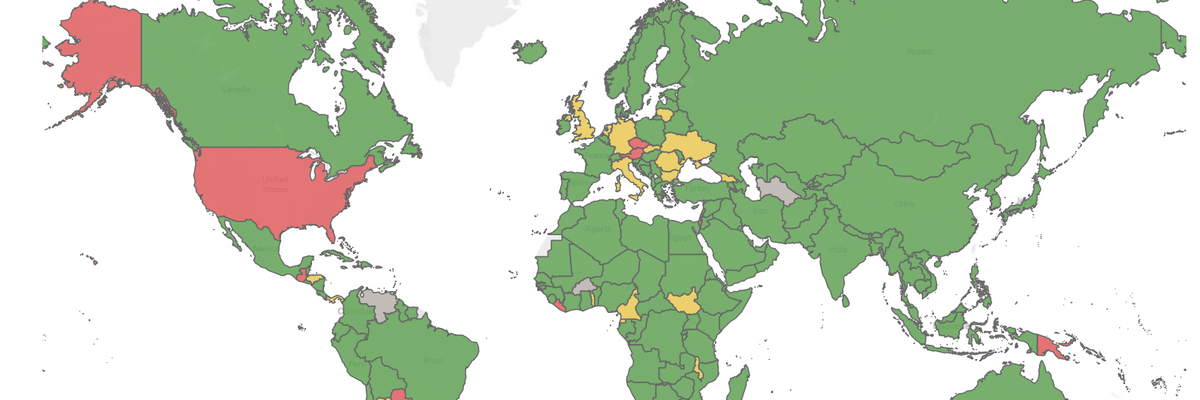

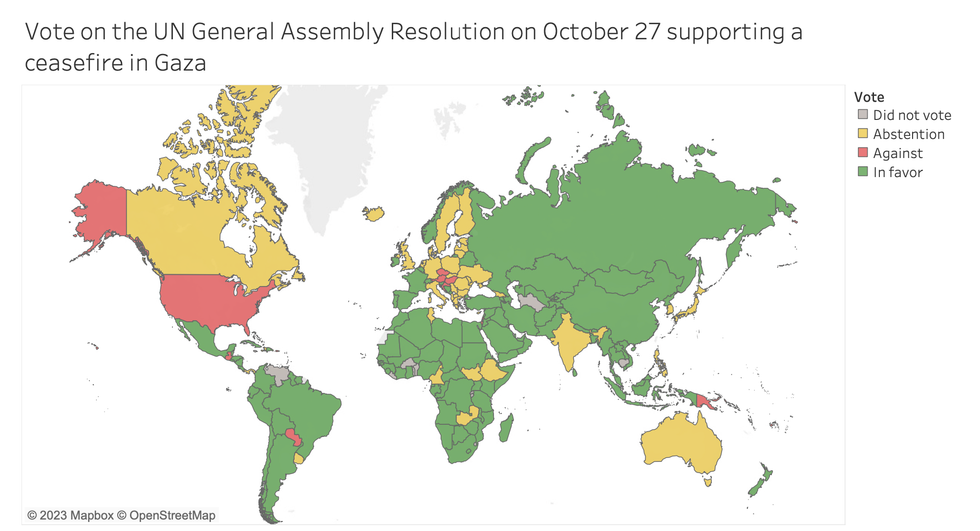

Mapping the votes of December 12 at the UN General Assembly (where every state has a single, equal vote with no veto powers) reveals massive support across the Global South (but also among many European states and U.S. allies in Asia, Japan and South Korea) for an unconditional ceasefire in Gaza.

This is as clear a diplomatic message as it gets: that Washington, now starkly isolated on the issue, should be using its leverage to end Israel’s relentless bombing campaign in Gaza. The support was even greater than the October 27 resolution which called for a “humanitarian truce” — with, among others, India, Philippines, Ethiopia, Zambia, and Fiji coming over to a ceasefire in the latest vote.

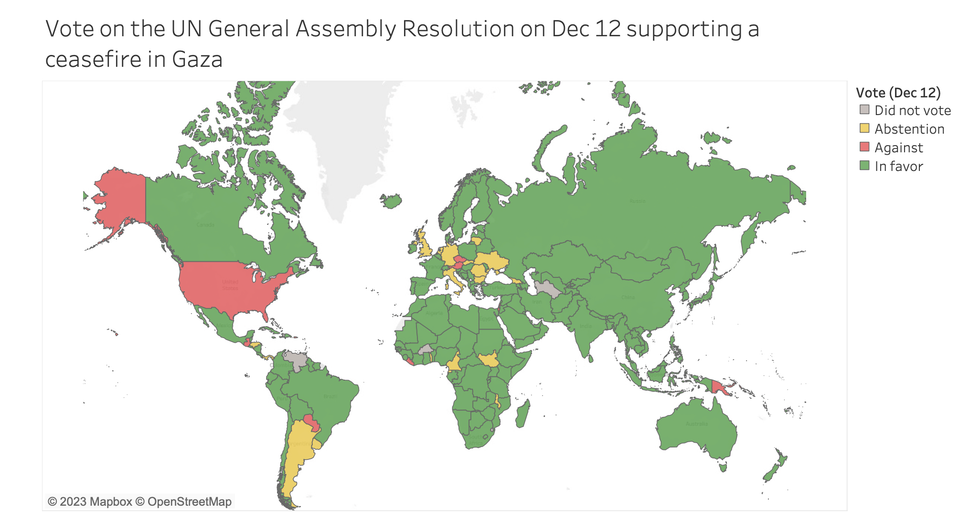

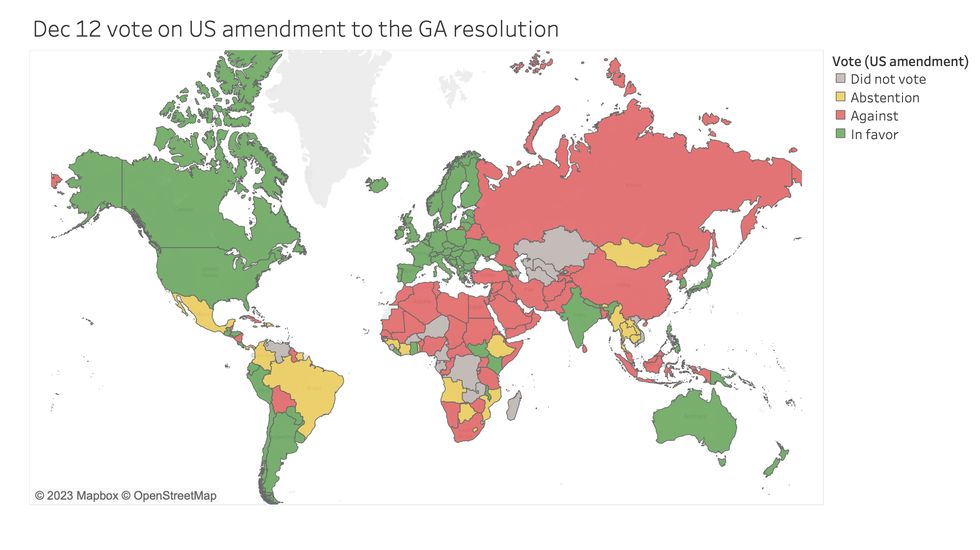

However, the Global South had varying preferences on the amendment introduced by the U.S. condemning Hamas (but not Israel) by name and its “heinous terrorist attacks” on October 7.

Here a divide is apparent between mainly Muslim-majority states — almost all of which voted against the amendment — and other Global South states. Thus a contiguous belt stretching from Mauritania in western Africa to Pakistan opposed the amendment, as did Muslim-majority Indonesia and Malaysia. They were joined by South Africa, Cuba, Bolivia, Uganda, and a few other non-Muslim majority states.

The rest of the Global South — including India, Philippines, Thailand, Brazil, Mexico, Peru, Ghana, and Kenya — abstained, did not vote, or supported the U.S. amendment.

- Who's afraid of the big bad Global South? ›

- UN Gaza vote: US isolation in the Global South near total ›