There has been an extraordinary flurry of announcements from the Trump administration about its preferred domestic and international policies since January 20.

Policies have been threatened, announced, postponed, canceled, and reinstated with greater or lesser severity. But underneath this hyperactivity, a clear pattern of economic policy preferences is emerging.

The White House has the following goals — shrink America’s trade deficits; use economic pressure to force countries to align with U.S. goals; recalibrate America’s strategic interests and the balance of U.S. and allied defense spending; maintain the central global role of the dollar; and keep interest rates low by encouraging inflows of foreign capital into U.S. government debt.

It is less clear that all these goals can be achieved simultaneously, as American actions provoke reactions from other governments and financial markets. Policies that seek to reduce the U.S. trade deficit and pare back the defense umbrella could lead to economic and political reactions elsewhere that impact the preservation of the dollar’s centrality and push up America’s interest rates.

Stephen Miran, head of the Council of Economic Advisers, has acknowledged that “demand for dollars has kept our [U.S.] interest rates low.” And Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has argued that global trade imbalances are in good part driven by insufficient consumption in Europe and Asia.

But the accounting counterpart of large U.S. trade deficits is a large net flow of dollars overseas, thus creating a demand for a place to store those dollars, including U.S. Treasuries. Thus, basic arithmetic means that the goal of reducing U.S. trade deficits could reduce demand for U.S. Treasuries and put upward pressure on interest rates. Pushing for sharp increases in defense spending outside the U.S. could lead to, as I previously noted, “allies borrowing and spending more on their own defense, creating alternatives that can compete with Treasuries for global investors’ favor.”

Miran has suggested ways to square this circle, at least in part. For example, allies could “boost defense spending and procurement from the U.S., buying more U.S.-made goods, and taking strain off our servicemembers and creating jobs here.” Or “they could simply write checks to Treasury [sic] that help us finance global public goods.”

His idea is that greater burden-sharing could benefit the U.S., whether through more export business for defense contractors (thus reducing the trade deficit), or more revenues for the Treasury from the provision of “defense as a service.” All this could be described as an attempt to monetize primacy.

However, the very definition of allies may have become more uncertain as patterns of national interest become more fluid and situational, potentially pushing customers away from long-term dependence on American military technology. For example, concerns have emerged in Europe about a potential “kill switch” embedded in American hardware. These worries are overblown, but the denial of software upgrades was already a tool of statecraft under President Biden. Even so, the U.S. is so far ahead in many defense technologies that other countries have few indigenous options at the same level of sophistication. So Europe is splitting the difference in its defense ramp-up, both buying from the U.S. and increasing domestic production over the long term.

Current policies might also be eroding a broader quid pro quo that underlies America’s historically unique status as the world’s largest debtor AND provider of the dominant global currency. Britain was the world’s largest creditor in 1914, a status that was formally transferred (along with the mantle of dominant-currency provider) to the U.S. by 1945. But by the 1980s, a different bargain emerged — the dollar’s centrality endured even as the U.S. became an external debtor but provided both a defense umbrella and a market for the world’s goods.

One question is whether that unique status is dented by a reduced American willingness to perform both those roles. For example, Japan’s finance minister has mused that his country’s Treasury holdings could play a part in tariff negotiations with the U.S.

The underlying quest for low interest rates and persistent dollar centrality has also led in another direction — encouraging the expansion of dollar stablecoins. These are globally transferrable privately issued digital tokens that guarantee that they will hold a par value to the dollar. The twin rationale is that this will solidify global “dollar dominance” by enabling private holdings of a digital version of the currency around the world, while also forcing the issuers of such stablecoins to hold U.S. Treasury debt, increasing demand for the same.

Such vehicles could create financial stability issues elsewhere by enabling capital flight, but this might not disturb the administration (even if foreign financial meltdowns have in the past impacted American exporters and investors). However, there is no guarantee that foreign money flowing into digital dollars would react differently than similar flows into conventional dollars should markets fear heightened political pressures on the Fed. Even the U.S. could be hit by financial instability enabled by widening the mechanisms of instantaneous cross-border digital currency transfers.

Beyond some of the inherent contradictions across these multiple goals, America’s efforts in this direction are also pushing other countries and regions to reduce their vulnerability to U.S. economic and monetary pressures. ECB President Christine Lagarde has called for measures to deepen European integration in order to bolster the euro as a competitor to the dollar. The EU has long talked about this with less follow-through. Nevertheless, a key market indicator of European structural integrity — the spread between Italian and German debt — is at multiyear lows, suggesting investors believe this time may be different.

China’s central bank is also pushing to internationalize its currency, something that will be harder than in Europe, given that China imposes more stringent controls on capital flows. However, there are many signs that Chinese banks are lending more across borders (particularly in Asia) in renminbi rather than in dollars, expanding the international role of China’s currency into areas where the dollar has been predominant.

These developments will all take time, but it may turn out the U.S. is juggling too many balls of international economic diplomacy all at once.

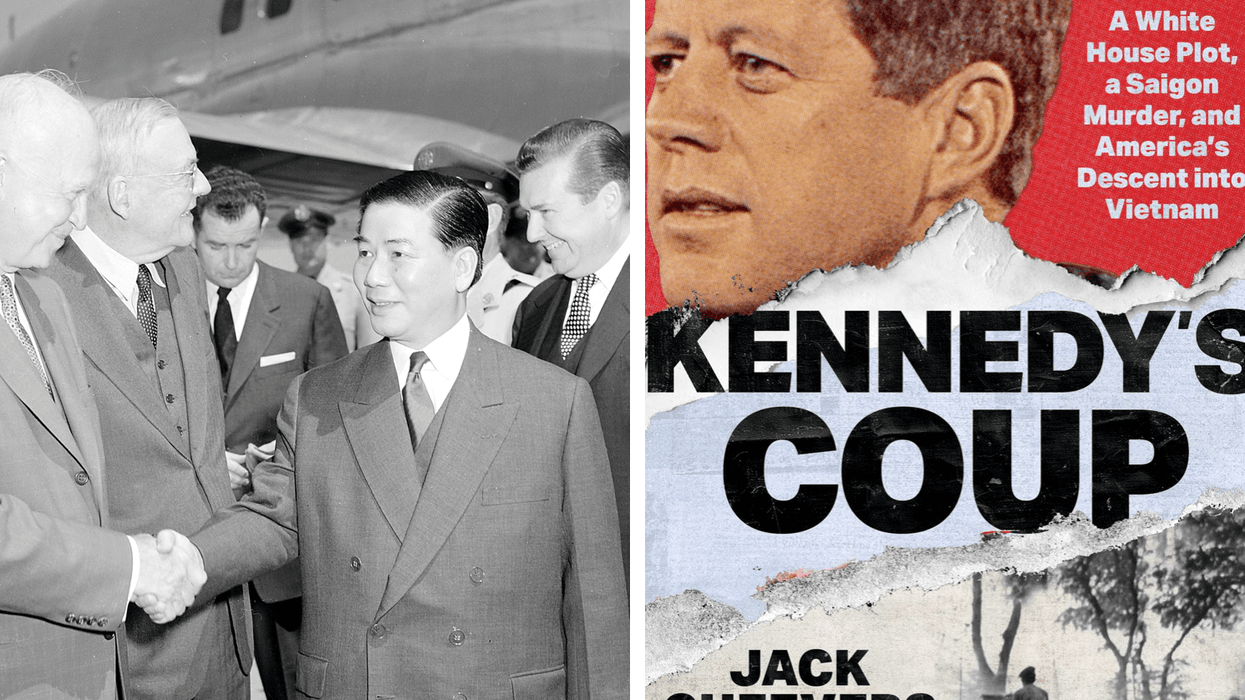

President John F. Kennedy and Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. in 1961. (Robert Knudsen/White House Photo)

President John F. Kennedy and Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. in 1961. (Robert Knudsen/White House Photo)