The deterioration of nuclear arms treaties, especially within the context of the war in Ukraine, presents worrying trends not seen in generations as Washington and Moscow are one step away from direct conflict. The Doomsday Clock “now stands at 90 seconds to midnight–the closest to global catastrophe it has ever been,” according to the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

The Russian Duma has advanced plans to withdraw ratification of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test Ban Treaty, citing the need to restore parity with the U.S. which has yet to ratify the decades-old treaty.

While the decision to withdraw ratification will not be as damaging as America’s unilateral withdrawal from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty and the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty in 2002 and 2019, respectively, it serves as another reminder that attention must be directed towards addressing an increased nuclear threat, especially as war rages in Ukraine. The U.S. must lead by example — like ratifying the CTBT — when it comes to international treaties it expects other countries to abide by.

Unsurprisingly, following Russian President Vladimir Putin’s comments on the subject earlier this month at the Valdai International Discussion Club, the legislative process for de-ratification began at pace. Officials have clarified that, at present, Moscow does not see a need to resume nuclear tests even if Russia were to withdraw.

The CTBT, adopted in 1996 by the United Nations General Assembly and ratified by 174 countries, prohibits nuclear weapon tests or explosions anywhere in the world. The treaty has never officially entered into force as several states have not yet signed on or completed the process of ratification, including China, India, Pakistan, Egypt, Iran, North Korea, Israel, and the U.S. Nevertheless, “the CTBT is one of the most successful agreements in the long history of nuclear arms control and nonproliferation. Without the option to conduct nuclear tests, it is more difficult, although not impossible, for states to develop, prove, and field new warhead designs,” notes Daryl G. Kimball, Executive Director of the Arms Control Association.

In part due to Russia’s war in Ukraine, Moscow has increased reliance on its nuclear arsenal in an attempt to deter escalation as its conventional forces have encountered stiff resistance by Ukrainian fighters heavily backed by American and European financial and military support.

Indeed, there have been several warnings (and even threats) from the Kremlin and the Russian security establishment, some more subtle than others, about Moscow’s willingness to defend what it views as its existential interests in Ukraine, ultimately with nuclear force if necessary.

Not to be outdone by their Russian colleagues, commentators in the U.S. and Europe appear comfortable calling Moscow’s bluff and encouraging an array of options for the intensification of the conflict.

The Biden administration, however, has generally approached the introduction of new weapon systems into the conflict with a healthy dose of moderation, so as to assess the reaction from the Kremlin. This deliberative process, even if opposed by many in the transatlantic community, is critical. Nevertheless, and as bitter as it is to accept, the uncertainty over “how much is too much” for Moscow does implicitly impose restraints on Kyiv’s backers.

While American and European commentators have proven right thus far, and no nuclear escalation has occurred, the greatest tragedy is that the day after they are proven wrong there will be nobody left to tell.

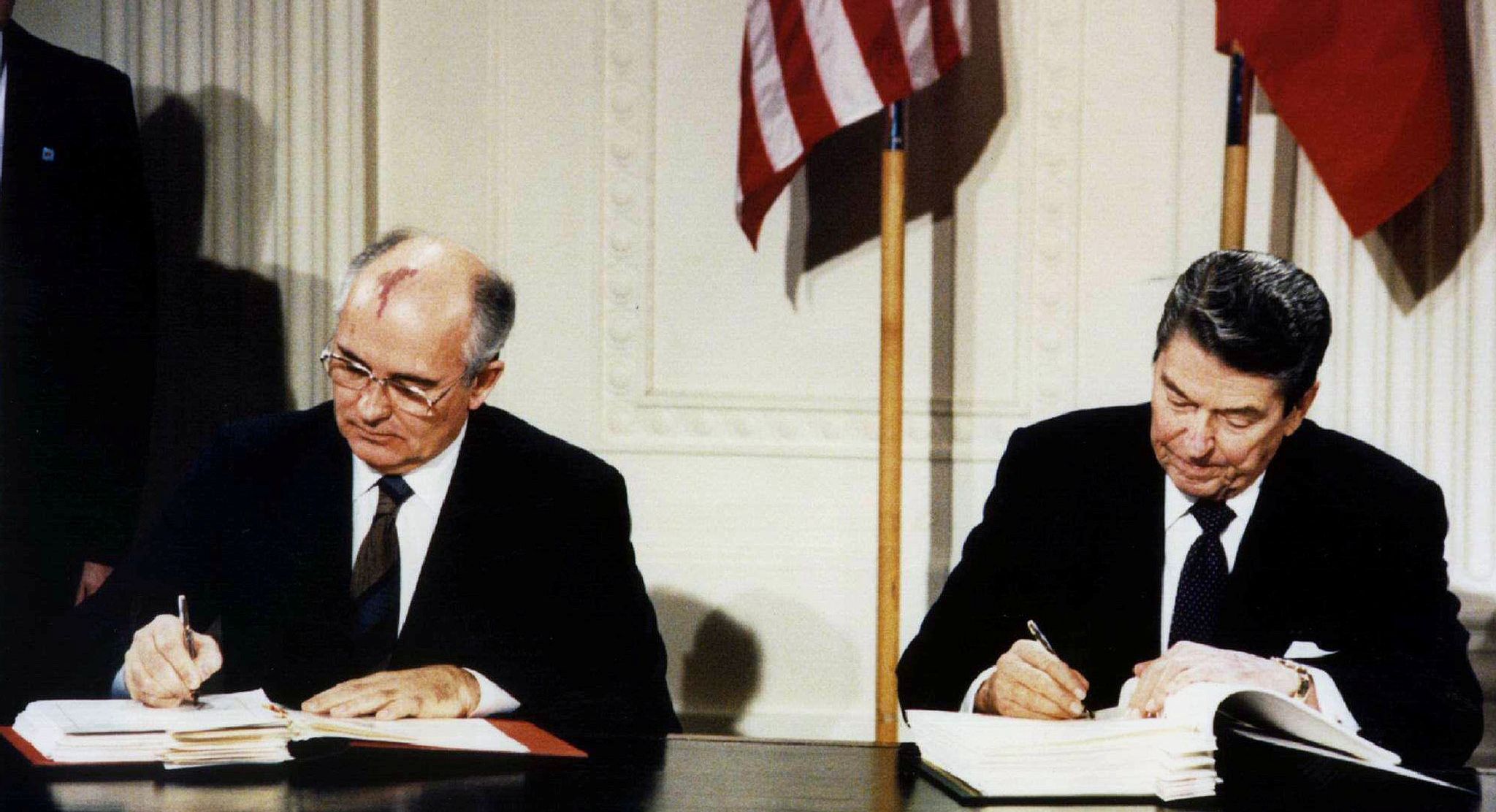

Following the near apocalyptic episode remembered as the Cuban Missile Crisis, leaders from the U.S. and the Soviet Union sought to establish mechanisms to prevent once again from being on the doorstep of nuclear annihilation. These began in 1963 with the Limited Test Ban Treaty and by 1985 Mikhail Gorbachev and Ronald Reagan jointly stated that “a nuclear war can never be won and must never be fought.” The two leaders eventually went on to sign the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, which represented the first time the U.S. and the U.S.S.R agreed to reduce the actual number of nuclear arms.

As strategic stability between the two most heavily equipped nuclear states on Earth continues to deteriorate and the deplorable state of diplomatic relations does not bode well for the return of nuclear treaties, China, Britain and others are seeking to modernize and enhance their nuclear capabilities. It’s also possible that more states may resort to developing their own nuclear arsenals, viewing the possession of such weapons as the only real means of self-defense in an increasingly disorderly world.

For its part, the U.S. is in the process of a $2 trillion, three decades-long initiative to upgrade its nuclear triad and accompanying infrastructure. A recently published report by the Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States paints an alarmist picture of the strategic threat the U.S. faces in the world today, and offers recommendations that will likely produce further instability.

As the Quincy Institute’s Bill Hartung recently wrote, “Astoundingly, the commission argues that these investments are not enough, and that the U.S. should consider building and deploying more nuclear weapons, even as it endorses dangerous and destabilizing steps like returning to the days of multi-warhead land-based missiles while placing nuclear-armed missiles in East Asia. These steps would only introduce more uncertainty into the calculations of China and Russia, making a nuclear confrontation more likely.”

The exorbitant expense that the maintenance and modernization of nuclear arsenals require, not to mention the otherworldly destruction that their usage entails, ought to be reason enough for the leading nuclear nations of the 21st century to work towards managing relations so as to eschew a new nuclear arms race.

Unfortunately, a return of serious strategic stability discussions in the short-term appears to be more wishful thinking. Nevertheless, these conversations will prove essential once the acute phase of the war in Ukraine is over and amidst a changing international context where responsible statecraft will be foundational to collective humanity’s survival.

The environmental degradation that occurred when unrestricted nuclear testing was the norm following World War II is still visible in parts of the world today. While today a de facto ban on nuclear testing has long been followed by the vast majority of states, even those not ascribed to the test-ban treaty, a return to previous levels of testing — when the global climate is already suffering severe challenges — must be averted.

- US ready for nuclear talks with Russia and China ‘without preconditions’: White House ›

- Russia's self-defeating move in pausing nuke talks with US ›

- Russian hawks push Putin to escalate as US crosses more ‘red lines’ ›

- Biden struggling on nuclear arms control | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Big US investors prop up the nuclear weapons industry | Responsible Statecraft ›

- John Kyl: The Return of Senator Strangelove | Responsible Statecraft ›