The Ukraine war, in addition to all the other ways in which one can describe it, has been a strangely humbling exercise for the foreign policy and military commentariat.

Pre-war projections of Russia’s rapid victory did not come to pass and, perhaps a fit of willful over-correction, were quickly replaced by fantastical tales of Russian collapse by Sunday (of March 6, 2022, not that anyone is keeping track), and a Crimea beach party slated for Summer 2023 when the Russians were to be expelled from the peninsula.

Predictions about the course of the war have become more qualified, understandably with a great deal more hedging, but old habits die hard. News of a 30-day ceasefire, agreed to by Ukraine and offered to Russia by the US, was greeted with furious posturing from all the stakeholders on both sides of the Atlantic.

A great many Kremlin allies, curiously joined by some Western neoconservatives, intoned that Moscow would flatly reject the proposal. There are good reasons why such projections were always unlikely.

For one, there is a clear transatlantic fissure between the Trump Administration and official European positions on this war. The former maintains it should end as quickly as possible with a negotiated settlement, whereas most EU and European leaders continue to demand Ukrainian battlefield victory and argue that “peace in Ukraine is actually more dangerous than the war.”

Russia’s outright rejection of the ceasefire proposal risked precipitating a convergence between these two and provoking President Trump to make the fateful decision — one from which, one hastens to add, he has so far vigorously refrained — to own this conflict much the same way that President Richard Nixon took ownership of the Vietnam war.

Further still, the incentives simply don’t line up. What sense does it make for Russia to jeopardize what could be a generational opportunity to normalize relations with Washington and reintegrate back into U.S.-led institutions just to seize a few more desolate villages in the Zaporizhzhian steppes?

But, though it would have been outlandish for Moscow to come back with abject refusal, there are several reasons why it was just as nonsensical to expect its unconditional acceptance.

First, there is the reality that ceasefires are by their nature conditioned on modality and parameters concerning implementation, monitoring, enforcement, and duration. All of these operational-level details will have to be discussed, indeed, negotiated, between Russia, the U.S., and Ukraine if a resilient ceasefire is to be established.

More broadly, ceasefires tend to benefit the side that’s losing — to wit, Ukraine. Insofar as this is a bilateral conflict between Russia and Ukraine (though there is a palpable sense in which it’s much more than that), the Russian side is therefore in a greater position to shape the terms of the ceasefire or push for other concessions in exchange for accepting it.

There is every reason to believe, as has already been reported, that Putin will seek a freeze on U.S. arms deliveries to Ukraine while a ceasefire is in effect — he is likewise reportedly interested in halting Ukraine’s mobilization efforts.

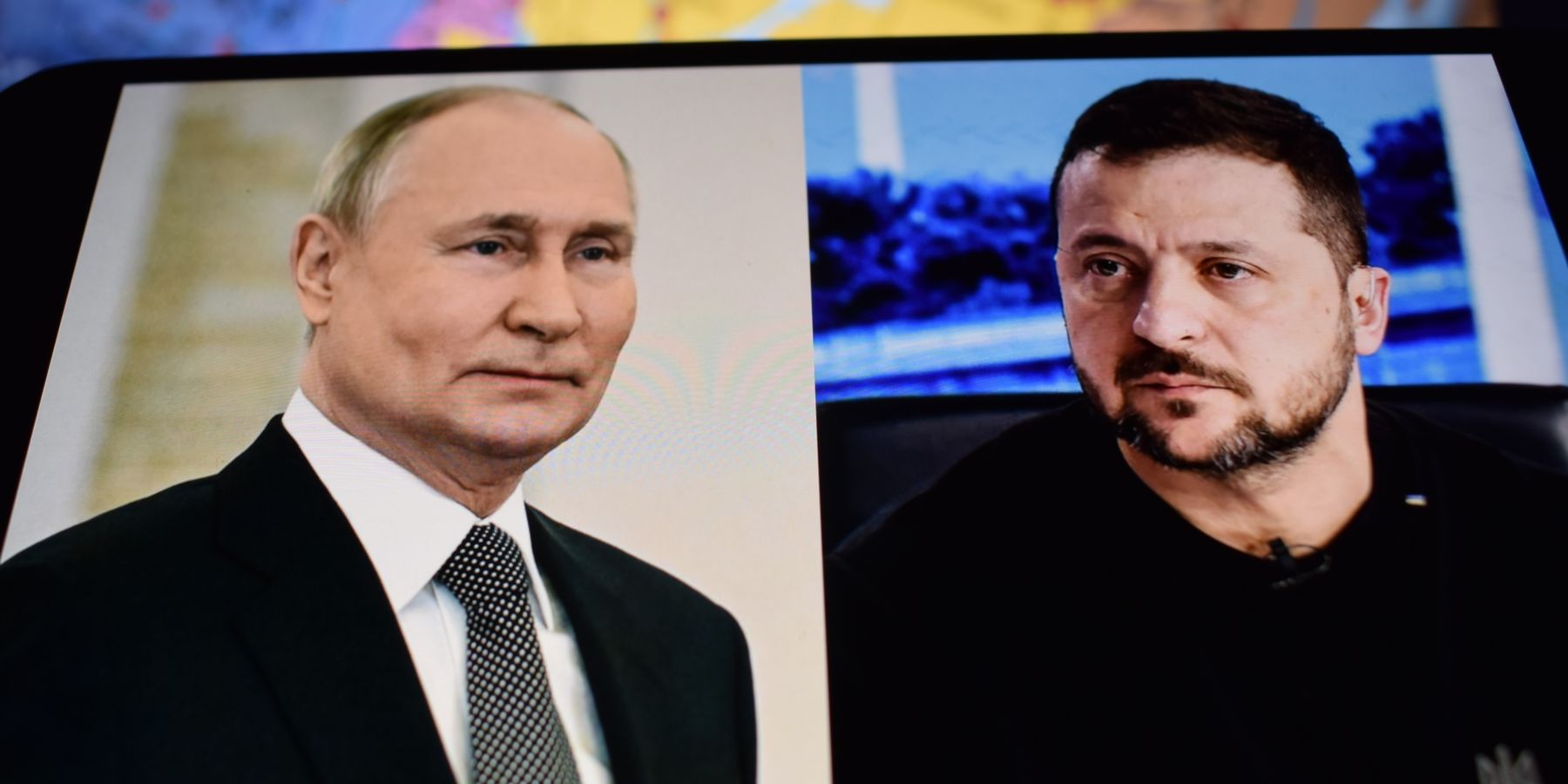

These terms are sure to leave Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky’s office unsmiling, but Zelensky is himself operating under severe constraints. President Trump has clearly demonstrated that he will not hesitate to pull the rug from under Ukraine, which is deeply reliant on the flow of U.S. weapons and intelligence sharing, if Zelensky tries to exercise a veto over the peace process.

No less importantly and perhaps somewhat less cynically, Zelensky no doubt realizes that his country and its valiant but harried populace stands to benefit tremendously — in any case, more than the Russians — from a cessation of hostilities even under unendearing terms.

Nevertheless, whether these Russian ceasefire stipulations are a red line or simply a bargaining position remains to be tested by the administration. There are any number of counter offers that can be made. For example, the White House can argue that completely severing security assistance to Kyiv compromises Ukraine’ security in a way that’s not conducive to long-term peace, but that Washington is prepared to place restrictions on certain types of security assistance and intelligence sharing as a good faith measure.

Alternatively, the administration can say that the ceasefire should not come with any strings attached, but that it is prepared to reduce the effective period to, say, 15 days as a way of mitigating the Kremlin’s stated concern that ceasefires may be used to buy time for Ukraine to rearm in anticipation for another round of fighting. In any case, U.S. officials should make clear to their Russian counterparts that a ceasefire, far from a goal in of itself, is merely the first step on the path to a durable settlement, and that they stand ready to work toward a roadmap to a peace deal both before and during a ceasefire.

Indeed, one of the most important steps that the US can take is to signal both publicly and behind closed doors to all three of the stakeholders — Europe, Ukraine, and Russia — that it is in it for the long haul when it comes to securing lasting peace not just for Ukraine but for all of Europe. For the former two, this serves as a crucial exercise in reassurance that will make unpleasant but necessary compromises in future negotiations easier to stomach.

It also sends Moscow the message that working with Trump is wiser than trying to outwait him, and that Washington is prepared for serious long-term engagement on the larger and even more difficult questions of the Russia-NATO relationship and Moscow’s place in the architecture of European security.