When did people stop fearing nuclear armageddon?

That’s what it can feel like, watching the movies of the last 25 years or so. When is the last time you saw a trailer for something even close to a Dr. Strangelove or even WarGames? (For all its acclamation, Oppenheimer was an intellectualized biographical drama focused on the man behind the bomb.)

Sure, apocalyptic disaster movies are still all the rage, but today they focus almost exclusively on pandemics, artificial intelligence, or natural catastrophes set off by global warming. At best, nuclear weapons may play a bit role in some terrorist scheme in a Mission Impossible or Jack Reacher plot, but in doomsday itself, like The Day After? Not in a very long time.

When a film “captures the zeitgeist” it means it is reflecting back society’s impulses and anxieties at any given moment, and sometimes, not always, offering a better understanding of where these culturally shared feelings come from and how, if necessary, to get past them. The fact is, 21st Century Hollywood no longer portrays the horrors of nuclear war because too many people feel removed from the fear of it.

So what about a movie in which the entire focus is that fear? For that, we have to go even further back.

One of the most successful films in this genre was made outside of Hollywood, produced by the only society in the world that has actually been a victim of nuclear war: Japan.

No, not Godzilla, the original metaphor for the violent birth of the atomic age. This one has no no generals, politicians, geopolitics, countdowns, or international crises.

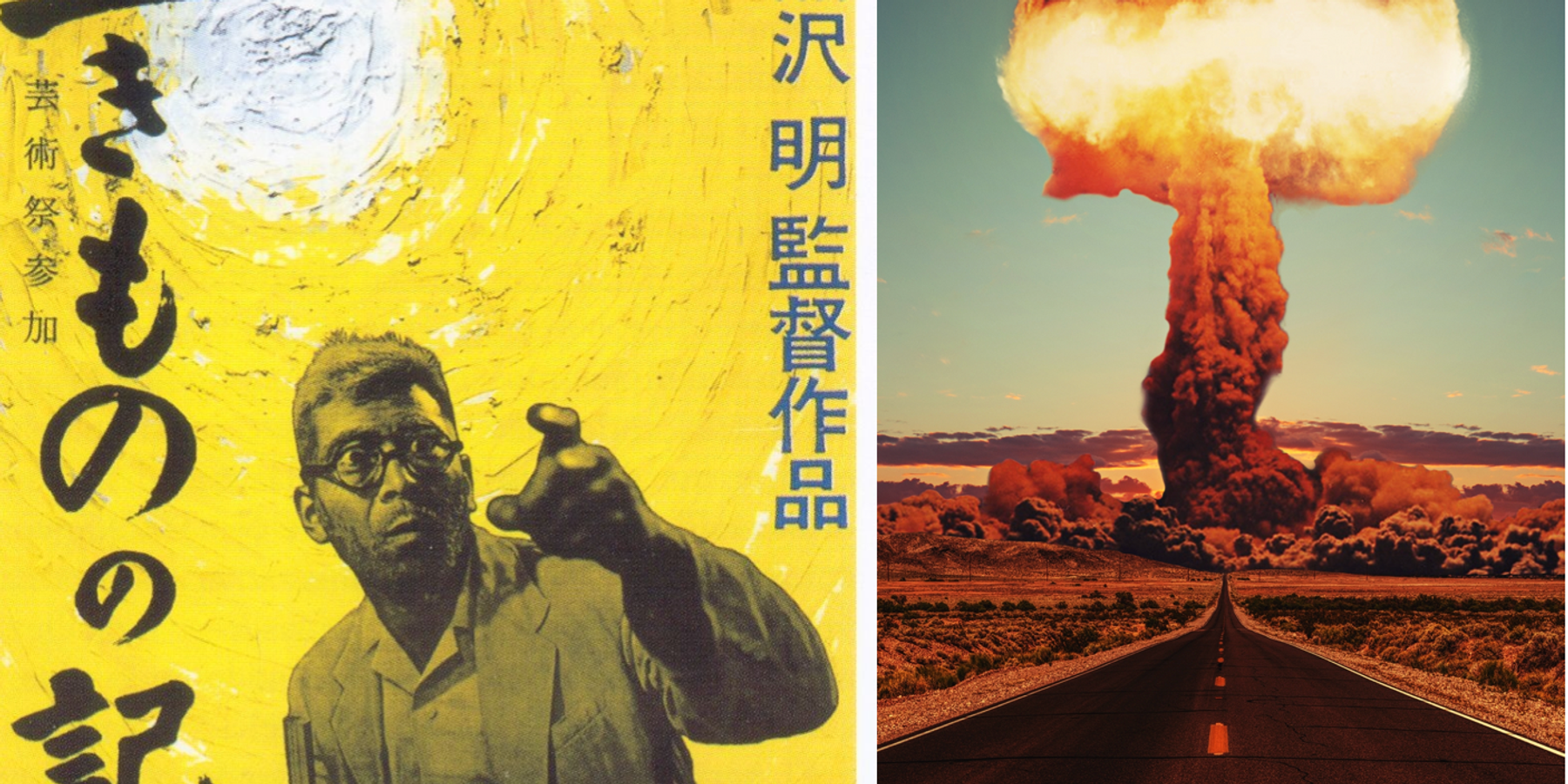

I Live in Fear (1955) comes from the mind of director Akira Kurosawa (1910-1998), whose body of work would later inspire western luminaries like George Lucas and Steven Spielberg. I Live in Fear, now being featured in the Criterion Collection, was intended to express Kurosawa’s own anxieties over the nuclear moment.

In it, a 35-year old Toshiro Mifuneplays an elderly, cantankerous factory owner named Kiichi Nakajima (complete with old-age makeup) who is convinced he must sell the foundry and move to South America in order to avoid the inevitable fallout from a looming atomic war.

His family is so distressed by his behavior that they take the issue of his competency to court. During the legal proceedings, one of the sons says that everyone has to die sometime, why does it matter how? To which Nakajima growls, “everybody has to die, but I won’t be murdered!”

His logic does not fall on deaf ears. “His only fault is going too far. But his anxiety about the bomb is something we all share…We just don’t feel it quite as strongly,” affirms one of the arbitrators, Doctor Harada, played by Kurosawa regular Takashi Shimura.

“We don’t build underground shelters or plan to move to Brazil,” says Harada. “But can we claim that the feeling is beyond comprehension? The Japanese all share it, to greater or lesser degrees. We can’t dispense with it so easily by just saying he went too far.”

Nuclear anxiety proves contagious, as Harada buys a book titled The Ashes of Death and becomes increasingly melancholic. “If the birds and beasts could read it, they’d all leave Japan,” he tells his own son.

Now placed in a conservatorship by his bickering family, Nakajima becomes increasingly desperate. During a chance encounter on the street, he berates Harada: “I keep thinking about the H-bomb, but all I can do is think! And the more I think, the more restless I become. But there’s nothing I can do! It’s a living hell!”

Gathering one last family meeting, Nakajima pleads with his children. “You say I’m paranoid, and maybe I am. But H-bombs really exist. War could break out at any time. If it does, it’ll be too late to get away.”

“I can’t let him die,” he wells up, pointing at his youngest, infant son. “I can’t let an H-bomb kill him before he’s even had a chance to live! I don’t care about myself, and I thought I’d have to give up on you. I thought at one point if I could at least save this baby — but you’re all my flesh and blood! I can’t leave you here! Please come with me, I’m begging you.”

But his family remains unmoved by his pleas, more worried by their father’s erratic financial decisions than any wayward bomb.

(Spoilers ahead).

Physically sick with stress, and now monomaniacally focused on forcing his family to move, Nakajima burns down his own foundry. Confessing to this act of arson, he’s overwhelmed by the pain and despair expressed by his family and his many (now former) employees. This confrontation is his mind’s final break, as he crawls through a mudpatch promising to bring everyone to Brazil with him.

Committed to a sanitarium, Nakajima is visited by a still depressed Harada. His madness has left him convinced that he’s been transported to another planet, the only place truly safe from the danger of nuclear weapons. “By the way, what happened to the earth? Are many people still left behind there?” he asks Harada. Then, glancing out the window, he becomes frantic looking at the fiery sun in the sky. “It’s burning! The Earth has finally gone up in flames,” he exclaims, waving his arms and shuffling around the room.

I Live in Fear is considered one of Kurosawa’s minor works, lost in the shadow of his masterpieces, Seven Samurai, High and Low, and Yojimbo. But its street-level view of nuclear anxiety has made I Live in Fear timeless, and its premise much more relevant today than most of the Cold War thrillers which would follow in the decades since.

A viewer’s takeaway might be the same as one of Nakajima’s psychiatrists: “Is he crazy? Or are we, who can remain unperturbed in an insane world, the crazy ones?” We need not be paranoid or obsessed, but neither should we be apathetic to the real threat that nuclear weapons pose to us today. Perhaps we do not need a “Day After” to show us what World War III would look like, but a healthy dose of fear, and what it looks like wouldn’t hurt either.