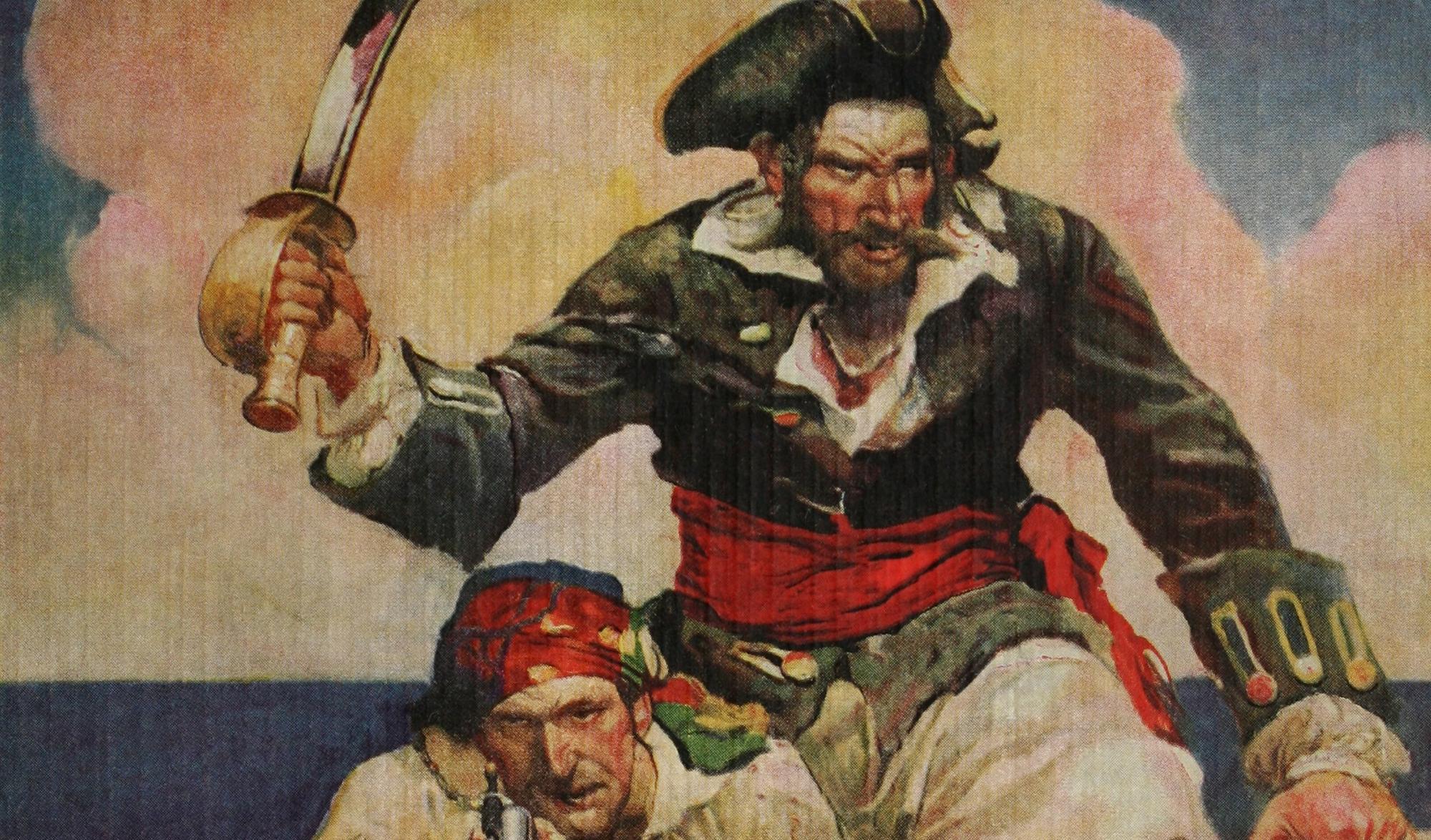

Just saying the words, “Letters of Marque” is to conjure the myth and romance of the pirate: Namely, that species of corsair also known as Blackbeard or Long John Silver, stalking the fabled Spanish Main, memorialized in glorious Technicolor by Robert Newton, hallooing the unwary with “Aye, me hearties!”

Perhaps it is no surprise that the legendary patois has been resurrected today in Congress. Sen. Mike Lee (R-Utah) has introduced the Cartel Marque and Reprisal Reauthorization Act on the Senate floor, thundering that it “will revive this historic practice to defend our shores and seize cartel assets.” If enacted into law, Congress, in accordance with Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution, would license private American citizens “to employ all reasonably necessary means to seize outside the geographic boundaries of the United States and its territories the person and property of any cartel or conspirator of a cartel or cartel-linked organization."

Although still enshrined in Constitutional canon, the fact that American citizens can be empowered to make war in a wholly private capacity skirts centuries-long understanding over “the laws of war.” At best, a letter of marque is to be issued only in the circumstance of a legally issued state declaration of war. Hence, a licensed corsair or privateer is akin to a sheriff’s deputy, who even as a private armed person is sworn to abide by the order and laws of the state.

History, however, does not support this best case. The plain truth — again, over centuries — tells the story of private naval enterprise practically unfettered. These are no Old West deputies under direct command of a U.S. Marshal. These are licensed raiders, serving autonomously, as flag-waving freebooters.

A letter of marque, the King’s signature notwithstanding, is simply licensed predation at sea — and this is under the most favorable aegis, when said letter is actually granted to a private person when the nation is at war. Yet most often, for the last 700 years, a letter of marque is really no more or less legal piracy.

But why would states want to create such a legal justification for attacking rivals and competitors, pesky inconvenient minor states, or in this case, drug traffickers?

Rep. Tim Burchett (R-Tenn), who introduced his own bill in February, proudly confesses to the Washington Post that letters of marque would give “the president some constitutional power to go after the Bad Guys and not wait on Congress to give their permission.”

Here we come to our world reality — the exact same reality that has held for seven centuries — and that is this: States want to degrade their rivals, competitors, and their pesky minors without having to go to actual war. This is an ironclad rule of “international relations” that is also (forever cynically) unspoken. War continues as it has always, outside of any laws.

“Private” legions have often made private war, often at the behest of state authority, down the centuries. Think: William Walker’s Nicaraguan filibuster, the Jameson Raid on the Transvaal, the Freikorps rampaging in the Baltics, the Czech Legion’s battle across Siberia, Claire Chennault’s Flying Tigers, Mike Hoare’s Congo Commandos. When they do state bidding, we call such fighting bands “proxies” — whether or not they operate with an official letter. The United States has been an eager — if not a standout — puppetmaster of privateers.

Like all privateers, however, the very autonomy of these armed groups leads them into gray areas outside of state sanction, into freebooting piracy. When they leave, or are let go by their state employers, they can easily go over to the dark side. Such was the fate of many most fabled pirate captains.

Yet many others, from Elizabethan Sea Dogs to Ottoman corsairs to Dutch vrijbuiter, worked their way back into the good graces of royal court — and the law — to great honor and even greater riches.

The dirty jobs that need doing

Two takeaways for today: First, the so-called laws of war are infinitely fungible, according to the desires of the state. Second, privateers — and pirates — are only meeting the compulsive need of legal authority to find someone who will go over to the dark side of the law for its own purposes.

After the grueling Napoleonic Wars, European powers tried to more decorously regulate the laws of war. In 1856, the Declaration of Paris, in the aftermath of the Crimean War, outlawed privateering altogether. The U.S., however, refused to sign. The U.S. Navy did, however, abolish prize money for naval crews in 1899, ostensibly to discourage piratical excesses at sea.

Yet, when there are dirty jobs that need doing, and the state seeks to avoid embarrassment through plausible deniability, it will always, unfailingly, turn to a willing proxy. Although the letter of marque, resurrected, lies at present merely in the realm of “sometimes a great notion,” the assets of both Washington Imperial and Crown covert agencies are even now attacking international shipping in the Black Sea, working from the media cover that these are Ukrainian strikes.

So why go to the trouble of reviving a troublesome and long-buried marque of state piracy from bygone days? Perhaps administration boosters want to widen the scope and means of U.S. seapower in decline. Perhaps they want to “spread the wealth” when it comes to making war, so that it is not so pointedly a government-only enterprise. Maybe some believe they can clothe a dirty war in flamboyant raiment, by invoking the romance of another age.

Judging from social and old-style media alike, there are legions of vocal patriots champing and clamoring to prime the frizzen and grab a cutlass. “Unleash the Privateers!” cries one highly respected military analyst. Robert Newton fans are almost ecstatically onboard.

Perhaps this rogue gang in Congress is truly channeling the Trumpian battlecry: Make War Aargh! Again

- Proposed war authorization could allow Trump to target 60+ countries ›

- Not Blackwater or Wagner, Americans in Gaza are 100% mercenaries ›