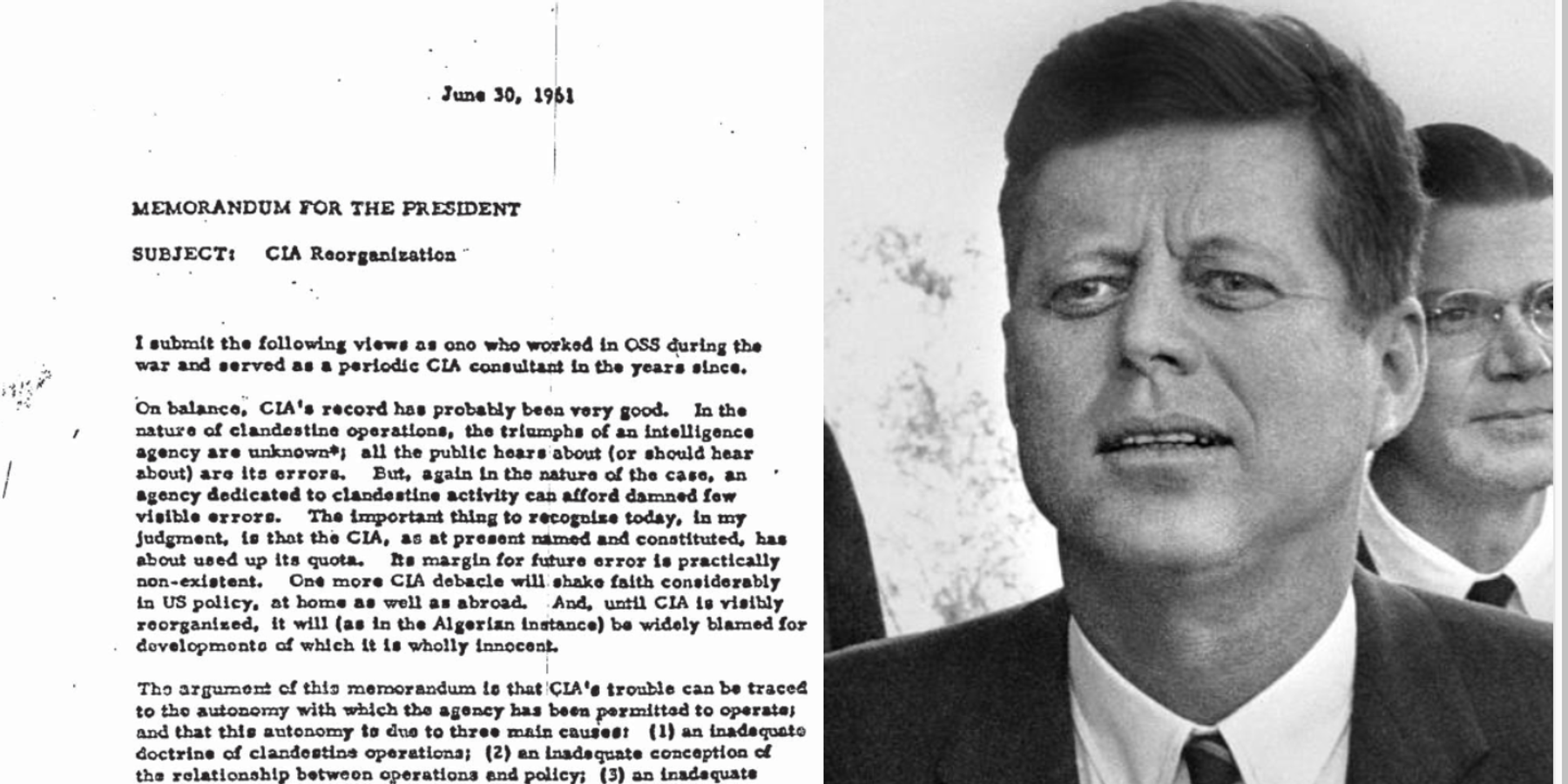

When the final, declassified records from the John F. Kennedy assassination files were posted on the National Archives’ website last week, the first document researchers and reporters searched for was White House adviser Arthur Schlesinger Jr.’s June 1961 memorandum to the president titled “CIA Reorganization.”

ABC News led its initial coverage on the release of the JFK papers with that document, quoting Schlesinger’s now unredacted, dramatic, statistics that showed that the "CIA today has nearly as many people under official cover overseas as [the] State [Department].” The New York Times also featured that document with a headline “A Kennedy aide worried that the C.I.A. threatened the State Department’s power.”

Meanwhile, the National Security Archive (where I work) posted a fully blacked out page 8 from when the document was first declassified, juxtaposed with the now fully unredacted page revealing Schlesinger’s detailed report to the president that “47 percent of the political officers serving in United States embassies were CAS ” — agents working under diplomatic cover known as “Controlled American Sources.”

“Sometimes the CIA mission chief has been in the country longer, and has more money at his disposal, wields more influence (and is abler) than the Ambassador,” as Schlesinger warned Kennedy about the CIA’s negative impact on the exercise of responsible U.S. statecraft. “Often he has direct access to the local Prime Minister. Sometimes…he pursues a different policy from that of the Ambassador.”

Newsworthy revelations, to be sure. But lost in the media focus on the final secrets of this one document is the broader historical significance of the entire 15-page memo. Since it was first partially declassified over 20 years ago, Schlesinger’s secret proposal on “CIA Reorganization” has captured a pivotal moment in the CIA’s controversial history — the brief interlude following the disastrous failure of the CIA-organized paramilitary invasion of exile forces at the Bay of Pigs, when the Kennedy White House seriously considered reconfiguring the Agency and re-distributing its clandestine and intelligence-gathering missions to other departments.

With the notoriety the document is now receiving, along with other records recently released under the Kennedy Assassination Records Act, the backstory of this unique juncture in the history of covert operations can now be told.

Bay of Pigs: Scattering the CIA to the winds

"How could I have been so stupid as to let them proceed?" President John Kennedy asked his advisers following the CIA's infamous fiasco at the Bay of Pigs in April 1961. Beyond the fact that the U.S. invasion of Cuba was an egregious act of aggression — violating international law and Cuba’s sovereignty — its failure was a catastrophic embarrassment for JFK, only weeks into his White House tenure.

Kennedy held CIA director Allen Dulles, and his deputy for covert operations Richard Bissell, personally responsible for deceiving him on the prospects for success of the ill-planned paramilitary assault. Indeed, as he processed the implications of the failed invasion, Kennedy vented his desire to “splinter the CIA into a thousand pieces and scatter it into the winds.”

That concept was more than angry rhetoric; the president actually set in motion a secret set of deliberations on breaking up the intelligence, espionage and covert action functions of the CIA and subordinating its operations to the State Department. Kennedy tasked one of his top White House advisers, Arthur Schlesinger Jr., as well as the President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board (PFIAB) — the high-level team of wisemen who monitored the intelligence community on the president’s behalf — to consider this option.

The special commission Kennedy appointed to investigate the debacle in Cuba, chaired by General Maxwell Taylor, also addressed what came to be known as “CIA reorganization.”

In his Pulitzer-winning account, “A Thousand Days: John F. Kennedy in the White House,” Schlesinger briefly alluded to this effort. The Bay of Pigs “stimulated a wide variety of proposals for the reorganization of the CIA,” he wrote. “The State Department, for example, could not wait to separate the CIA’s overt from its clandestine functions, and even change the Agency’s name.”

In fact, it was Schlesinger himself who suggested various new “blameless titles” for a reconstituted CIA, such as “The National Information Service” and “The Foreign Research Agency.” And it was Schlesinger who presented the harshest critiques of the Agency to the President, and the most concrete proposals to splinter it apart and reconstruct its functions under State Department control.

The Schlesinger Memoranda

Schlesinger presented these arguments in two lengthy secret memorandums for the president. The first, dated May 18, 1961, and titled “How to Organize an Intelligence Service: Implications of the British Example,” responded to Kennedy’s request that Schlesinger examine the “British intelligence set up” to determine “what of value there might be for our own thinking about CIA reorganization.”

The memo illuminated the structure of the British intelligence service as it evolved after WWII, focusing not only on how it separated the functions of intelligence gathering from special operations but also how MI-6 coordinated with, and was essentially subordinate to, the British Foreign Ministry. “What is of special interest in the British experience is not the division between intelligence and operations, but the means by which the clandestine service is kept under continuous policy control,” Schlesinger advised Kennedy.

The British approach provided lessons to be learned from the Bay of Pigs debacle, Schlesinger argued, because the State Department had been kept completely in the dark about planning for the covert invasion. The CIA’s “non-consultation” prevented any independent policy oversight; there was no “son-of-a-bitch — a man charged with raising every question, forcing every objection, and picking every hole before a decision is made,” Schlesinger suggested. “In the Cuban discussions, the case against the operation was never fully stated.”

Most significantly, Schlesinger used the conclusions of this memo to advocate, perhaps for the first time inside the White House, against the U.S. conducting future CIA covert paramilitary operations like the Bay of Pigs. In a final section titled “Special Operations in an Open Society,” he suggested that “efforts to enforce secrecy in such situations (as through official misrepresentation, suppression of news, etc.) will, if successful, run counter to our whole national ethos, and in the long run will have a corrupting effect on the character of our society.”

Even worse for U.S. foreign policy interests, he pointed out, was if the effort to maintain secrecy and deniability over these operations failed — as in the case of Cuba. “If unsuccessful (and one can almost always be sure they will be unsuccessful), such efforts will cause apprehension and trouble at home, draw the world’s attention to the contradictions between our government’s professions and performance, make it hard for us subsequently to invoke treaty obligations or international law against the Communists, and permanently shake faith in our international decency and credibility,” he concluded.

In his now famous memo on “CIA Reorganization” submitted to Kennedy a month later, Schlesinger returned to those arguments. The document illuminated the main functions and missions of the CIA: Clandestine intelligence collection; covert political operations, undercover controlled American sources; and paramilitary warfare. He also issued a forceful critique of the CIA’s rogue autonomy.

“The contemporary CIA possesses many of the characteristics of a state within a state,” Schlesinger ominously advised President Kennedy. “CIA operations have not been held effectively subordinate to United States foreign policy.”

To remedy the lack of control and coordination over the CIA, Schlesinger offered concrete recommendations to carve up the Agency’s functions and distribute them to other departments, particularly the State Department. Under a newly restructured intelligence agency, “the State Department would be granted all clearance authority over all clandestine activity,” similar to the British model. The CIA’s operational branches would be “reconstituted” under a new agency.

“This new agency would be charged with responsibility for clandestine collection, for covert political operations and for paramilitary activities.” Schlesinger also recommended a second “semi-independent agency” that would focus on the collation and interpretation of intelligence. That agency would combine the CIA’s analytical division with the State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research.

With a degree of irony, Schlesinger suggested that this new agency “might well be located in the CIA building in McLean.”

The PFIAB pursuit

As special assistant to the president, Schlesinger had Kennedy’s ear. But he was not a lone ranger in his focus on CIA reorganization; at Kennedy’s behest, the president’s prestigious and highly secretive advisory board on intelligence also conducted an inquiry into the option of an Agency makeover. On May 15, 1961, just one month after the Bay of Pigs invasion, JFK personally attended a PFIAB meeting, clearly irate about the lack of supervision over the CIA.

According to minutes of the meeting released as part of the assassination records, the president “referred to a recommendation that covert action programs of the CIA may not have been worth the risk nor worth the great expenditures of manpower and money; that CIA concentration on such activities had tended to detract substantially from the execution of its primary intelligence-gathering mission; and that there should be a total reassessment of U.S. covert action policies and programs.”

The president made it clear that “someone in the White House should be constantly in touch with and on top of covert operations.”

Under the chairmanship of James R. Killian Jr., the PFIAB held two secret sessions in July 1961 to consider the opinions of U.S. intelligence officials on restructuring the CIA. At a meeting in early July, Roger Hilsman, the director of the State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research told the board that “he favored reorganizing the CIA along the general lines of the British Intelligence System.”

Hilsman recommended placing clandestine collection and covert political action operations “under the Department of State,” according to a PFIAB summary of the meeting. “[A]nd he would require that the State Department exercise policy control over all aspects of intelligence including political, psychological, propaganda, paramilitary and related covert activities.”

On July 18, the Board met with CIA Deputy Director for Plans, Richard Bissell, the official most responsible for the failed Bay of Pigs operations. “Mr. Bissell of CIA was invited to discuss with Board members his views on possible reorganization steps that might be taken…,” according to a declassified summary of the meeting.

But Bissell appeared to focus instead on the need for the president to publicly defend the CIA. “At one point during the discussion Mr. Bissell volunteered the suggestion that perhaps a step might be taken by the President to obtain a better public understanding and acceptance of the CIA’s responsibilities.”

The Taylor Commission

The special commission of inquiry, appointed by President Kennedy on April 22, 1961, as Castro’s forces captured the last of the CIA-sponsored 2506 Brigade invaders, also briefly explored the short-lived deliberations on revamping the CIA’s institutional functions.

Indeed, the Commission, chaired by Kennedy’s close friend General Maxwell Taylor, met immediately with CIA Director Dulles who immediately urged them to leave the Agency intact. “[R]ather than destroying everything and starting all over,” Dulles told the commissioners, “we ought to take what’s good in what we have, get rid of those things that are really beyond the competence of the CIA, then pull the thing together and make it more effective.”

Dulles joined the Taylor Commission, which held closed hearings on what went wrong at the Bay of Pigs between April and June, 1961.

As Tim Weiner recounts in his award-winning history on the CIA, "Legacy of Ashes,” one of the last witnesses to appear before Taylor Commission was veteran intelligence official, retired General Walter Bedell Smith. This exchange took place:

General Smith: I think that so much publicity has been given to CIA that the covert work might have to be put under another roof.

Commission: Do you think we should take the covert operations from CIA?

General Smith: It’s time we take the bucket of slop and put another cover over it.

On June 13, 1961, the Taylor Commission presented Kennedy with its report that included 11 pages of recommendations for improving CIA operations, paramilitary preparations, communications, and coordination. But “CIA reorganization” was not one of them.

Indeed, in the aftermath of the Bay of Pigs, the president did little more than tinker with the CIA as an institution. Kennedy soon ushered Allen Dulles into retirement; and by the end of 1961, also fired Richard Bissell.

In one of the more bizarre twists of bureaucracy, JFK assigned his brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, to the powerful position of chairman of the “Special Group Augmented” — the top secret inter-agency unit in charge of covert operations around the world. With RFK’s oversight, the CIA and the Pentagon soon launched another set of legendary covert operations against Cuba, codenamed “Operation Mongoose."

In the end, Kennedy ignored Arthur Schlesinger’s prescient admonition that “secret activities are permissible so long as they do not corrupt the principles and practices of our society, and that they cease to be permissible when their effect is to corrupt these principles and practices.”

If the president had heeded such warnings when he had the opportunity and inclination, the CIA’s legacy might not be replete with the corrupting scandals of Mongoose, assassination plots, the overthrow of democracy in Chile, support for repressive military dictatorships, the contra war, and the Iran-Contra scandal, among other infamous case studies in the dark history of covert operations.

Our history, and the history of so many other nations, might have been different.