The growing presence of China in Africa has captured the attention of both Africa and the West. As Chinese trade and investments have eclipsed those of Europe and the United States, their leaders have warned that Beijing is exploiting African resources, threatening African jobs, buttressing African dictators, and showing general disregard for human rights, good governance, and sound environmental practices. While leveling the same criticisms, African civil society organizations have noted with irony that the West has long engaged in similar practices.

Chinese interest in Africa—and Western concerns about Beijing’s influence—are not new. Understanding the current standoff requires an understanding of its history. The most recent wave of Chinese interest in Africa began during the Cold War. In April 1955, representatives of twenty-nine Asian and African nations and territories, and numerous liberation movements met in Bandung, Indonesia at the Conference of Asian and African States. Participants resolved to oppose colonialism and imperialism and to promote economic and cultural cooperation throughout the global south—then called the “Third World.” They voiced particular support for decolonization and national liberation in Africa. China played a key role in the conference and engaged with Africa in the Bandung spirit of African-Asian solidarity and cooperation. Between the early 1960s and the mid-1970s, China offered grants and low interest loans for development projects in Algeria, Egypt, Ghana, Guinea, Mali, Tanzania, and Zambia. It also sent tens of thousands of “barefoot doctors,” agricultural technicians, and solidarity work brigades to African countries that rejected neocolonialism and had been rebuffed by the West.

In Southern Africa, where white minority rule persisted in settler colonies and Portugal resisted African demands for independence, Beijing provided liberation movements in Mozambique and Rhodesia with military training, advisors, and weapons. When Western countries ignored Zambian pleas to more effectively isolate the renegade regimes, China established the Tanzania Zambia Railway Authority (TAZARA) and built a railroad that permitted Zambia to export its copper through Tanzania, rather than white-ruled Rhodesia and South Africa.

During the Cold War, as China sought allies in the global arena, its policies were motivated primarily by politics. After the Cold War, however, China’s priorities changed. Beijing had embarked on a massive program of industrialization and economic development that transformed the Chinese economy into one of the world’s most powerful. Africa was no longer viewed as an ideological proving ground. Instead it was valued as a source of raw materials and a market for Chinese goods, ranging from clothing, cell phones and electronics to artificial intelligence systems. China’ relationship with Africa was no longer one that showed sympathy for its plight, but instead mimicked those of the colonial and Cold War powers. Countries were valued according to what they could offer China materially and strategically.

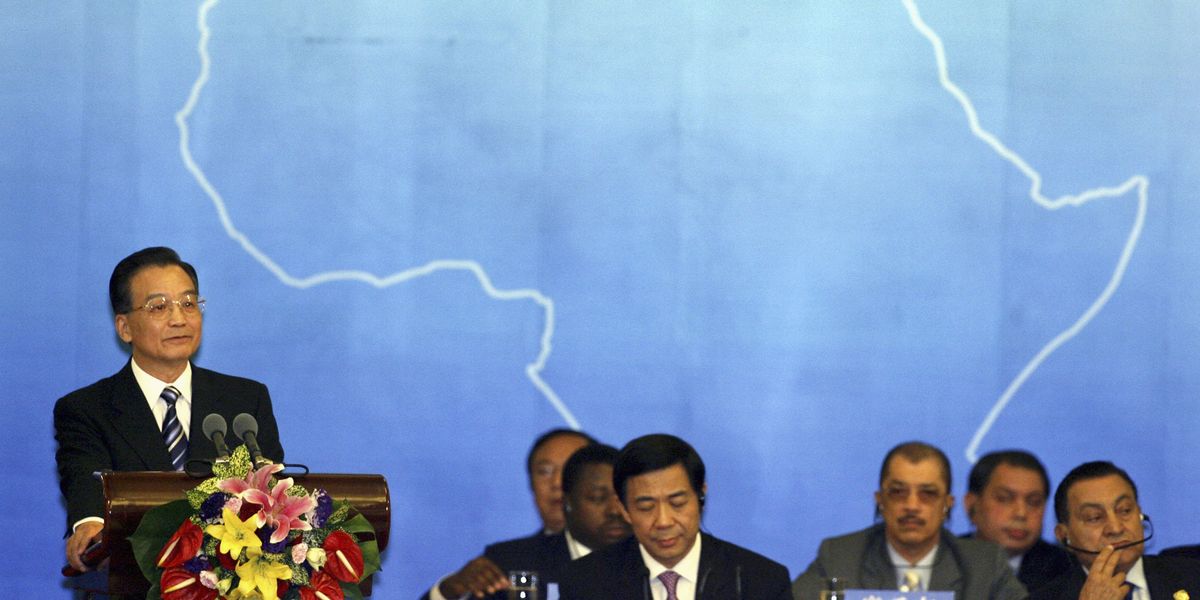

By the first decade of the twenty-first century, China had surpassed the United States as Africa’s largest trading partner, and more recently as Africa’s fourth largest source of direct foreign investment. In exchange for guaranteed access to energy resources, agricultural land, and strategic materials necessary to produce electronic devices and electric vehicles, China has spent billions of dollars on African infrastructure—developing and rehabilitating roads, railroads, dams, bridges, ports, oil pipelines and refineries, power plants, water systems, and telecommunications networks. Chinese enterprises have also constructed hospitals and schools and invested in clothing and food processing industries, agriculture, fisheries, commercial real estate, retail, and tourism. Recently, investments have focused on communications technology and wind and solar power.

Unlike the Western powers and the international financial institutions they dominate, Beijing has not made political and economic restructuring a condition for its loans, investments, aid, and trade. Although it has required that public works contracts be awarded to Chinese companies and that Chinese supplies be used, the agreements have not required a shift in economic models, adherence to democratic principles, respect for human rights, or the implementation of labor and environmental protections. While Beijing’s noninterference policies have been popular in ruling circles, civil society organizations have frequently criticized them. African labor, business, civic, and human rights organizations have observed that Chinese firms have driven African-owned enterprises out of business and employed Chinese workers rather than local ones. When they do hire African labor, Chinese businesses have paid poverty-level wages under conditions that have endangered worker health and safety. Moreover, the infrastructure projects have resulted in massive debts—although African countries still owe far more to Western powers and financial institutions than to China. Beijing’s practices, like those of Western powers, have resulted in a new wave of African dependency. Most importantly, Beijing has backed corrupt African elites in exchange for unfettered access to resources and markets, strengthening regimes that have pilfered their countries’ wealth, repressed political dissent, and waged wars against neighboring states.

In its battle for global influence, China has found in contemporary Africa what Western powers discovered centuries ago. Beyond resources and markets, it has garnered much-needed diplomatic support in the United Nations and other international organizations. As a permanent member of the UN Security Council, it has frequently challenged Western-sponsored initiatives that focus on human rights and governance issues, turning a blind eye to human rights abuses, political repression, and corruption. Until recently, it has opposed political and military intervention in the internal affairs of other nations. However, as Chinese economic interests in Africa have grown, it has recognized the need for peace and stability. As a result, Beijing has expanded its involvement in UN disaster relief, anti-piracy, and counterterrorism operations. Its decades-long policy of noninterference in host country affairs has been replaced in recent years by interventionist policies aimed at protecting its economic interests. In the early 2000s, Beijing joined UN peacekeeping operations for the first time, focusing on countries and regions where it had valuable investments and export markets. In 2006, for instance, China pressed Sudan, an important oil partner, to accept an African Union-UN peacekeeping force in Darfur, and in 2015 it worked with an East African subregional organization and Western powers to mediate peace talks in South Sudan. In 2013, Beijing joined UN peacekeeping efforts in Mali, motivated by its interests in the oil and uranium of neighboring countries.

Initially, China refrained from military involvement in strife-ridden areas, preferring to contribute medical workers and engineers. In 2007, it provided a 315-member engineering unit to the peacekeeping mission in Darfur, but no troops. However, as Beijing’s global stature and interests grew, so too did its military engagement. Chinese military presence was notable in UN peacekeeping missions in Burundi (2004–6) and the Central African Republic (2014–). In 2013, when Beijing supplied some 400 engineers, medical personnel, and police to Mali, it also provided combat troops, marking the first time Chinese combat forces had joined a UN operation. Similarly, in 2015, Beijing assigned 350 engineers, medical personnel, and other noncombatants to the UN peacekeeping mission in South Sudan. However, it also contributed an infantry battalion composed of 700 armed peacekeepers—the first Chinese infantry battalion ever deployed in a UN peacekeeping mission. By 2016, Beijing was contributing more military personnel to UN peacekeeping operations than any other permanent member of the Security Council.

The trend toward heightened Chinese political and military engagement in Africa culminated in 2017 when it joined France, the United States, Italy, and Japan in establishing a military facility in Djibouti, which overlooks one of the world’s most lucrative shipping lanes. The Djibouti base was China’s first permanent military facility outside its borders. Strategically located on the Gulf of Aden near the mouth of the Red Sea, the base has allowed Beijing to resupply Chinese vessels involved in UN anti-piracy operations and to protect Chinese nationals living in the region. It has also enabled the monitoring of commercial traffic along China’s 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, which links countries from Oceania to the Mediterranean in a vast production and trading network. This alliance will help China to safeguard its supply of oil, half of which originates in the Middle East and transits through the Red Sea and Djibouti’s Bab al-Mandeb Strait to the Gulf of Aden. Most of China’s exports to Europe follow the same route.

Although the United States decries Chinese imperialism, in reality it is fighting to maintain its role as the world’s single hegemonic power. Nonetheless, a growing number of African states are refusing to take sides in the new Cold War, rejecting Washington’s claim that it alone can protect their interests. Although Democratic and Republican administrations alike have promoted the notion that the U.S. must save the world from the “evil empires” that are threatening global security, it is the United States that has more than 750 bases in at least 80 countries, while China has only three. It is the United States that has joined at least 15 foreign wars since 1980, while China has joined only one. The U.S. security establishment favors containing or defeating China by bolstering military alliances abroad. It has established 29 military bases in Africa in resource-rich areas that have attracted the attention of both China and violent extremists.

Jeffrey Sachs, a Columbia University professor who has advised three UN secretaries-general, has referred to the US view of global security as “dangerous, delusional, and outmoded.” True security is not rooted in military ventures, he argues, but rather in the abandonment of hegemonic dreams and the building of alliances with other countries, large and small. Only then can the world begin to resolve the many environmental, energy, food, and social crises that threaten to devastate us all.

This piece was republished with permission from the New Left Review

- US official signals stunning shift in the way we interpret 'One China' policy ›

- Diplomacy Watch: China seeks to portray itself as peacemaker in Ukraine ›

- In great power diplomacy, is China beating US at its own game? ›