The head of Indo-Pacific Command, Admiral John Aquilino, recently warned members of the House Armed Services Committee about increasing cooperation among Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea and said, “We’re almost back to the axis of evil.”

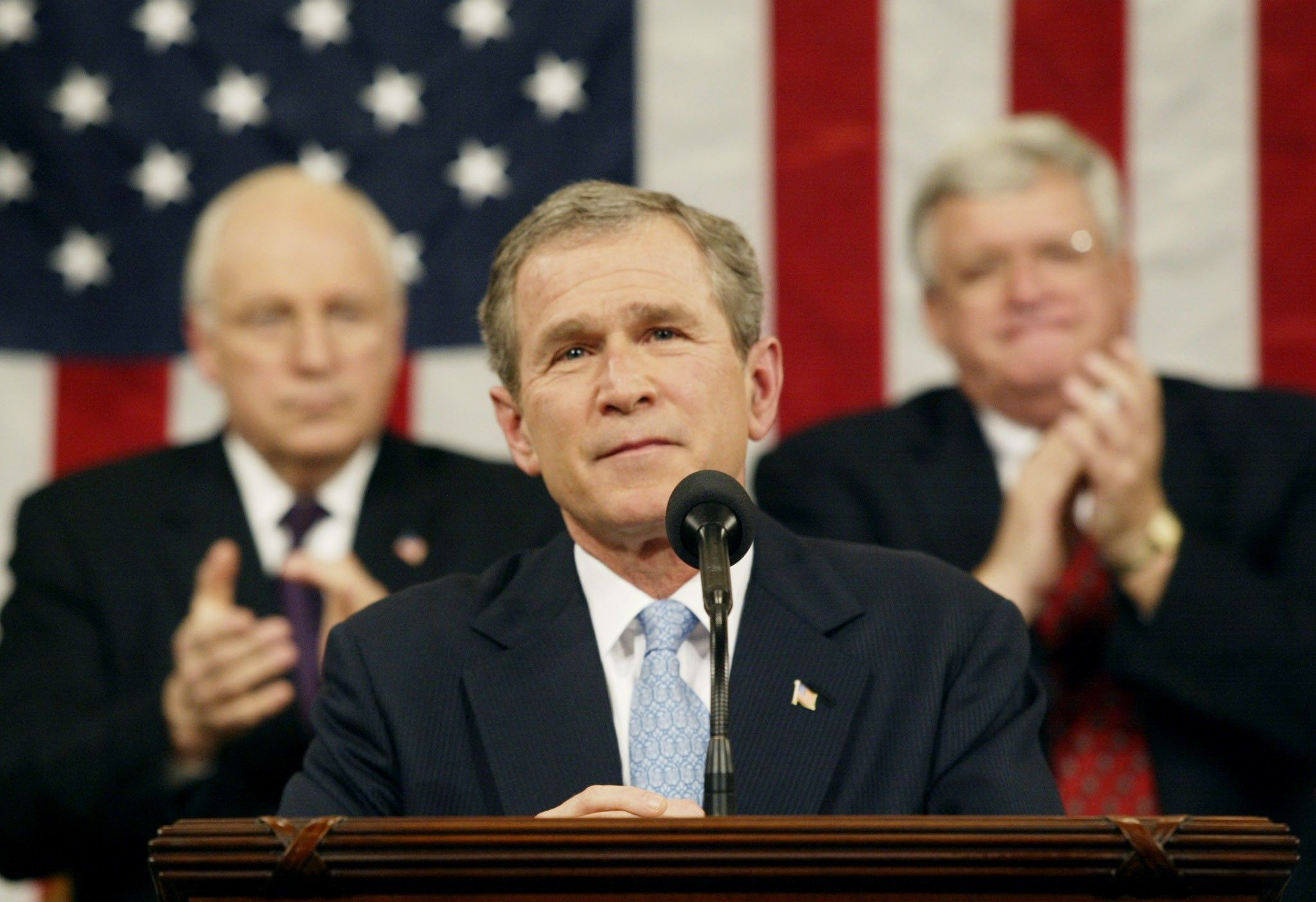

There has been something of a revival of this discredited Bush-era idea in recent years, and it has become more common for members of Congress and now high-ranking military officers to describe the relationships between various authoritarian states using some version of George W. Bush’s ridiculous phrase.

While it is true that there has been some increased cooperation between these four governments, it is dangerous and misleading to suggest that they form anything resembling a close alliance or coalition. If the U.S. were to “act accordingly,” as Adm. Aquilino recommended, it would risk driving these states much closer together and creating the very axis that U.S. officials fear.

Aquilino’s phrasing is revealing. When he said, “we’re almost back to the axis of evil,” that seems to suggest that he thinks there was a real one that serves as a model for the current group. The first “axis of evil” that George W. Bush denounced in his 2002 State of the Union address was made up of three states — Iran, Iraq, and North Korea — that were united only by Washington’s hostility to them. Iran and Iraq had long been enemies and remained so at the time, and North Korea was added to the mix so that it wouldn’t be entirely fixated on predominantly Muslim countries. These states weren’t working together, and two of them were opposed to each other.

There was no axis then, and there still isn’t one now.

The purpose in tying together unrelated adversaries has always been to exaggerate the size of the threat to the United States to scare policymakers and the public into supporting more military spending and more overseas conflicts. If inflating the threat from any one adversary isn’t enough to instill sufficient fear, the invention of an axis that includes some or all adversaries around the globe can be very useful to hawks. Because it automatically calls to mind World War II and the fight against the Axis Powers, it also helps them to demonize the other states and smother domestic dissent. Supporters of hawkish policies in each region will then have an incentive to embrace the axis rhetoric and reinforce these views among their political allies.

Several current and former elected officials have referred to a new “axis of evil” in recent months. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) used the phrase last October and demonstrated its threat inflating potential: “It’s an emergency that we step up and deal with this axis of evil — China, Russia, Iran — because it’s an immediate threat to the United States. In many ways, the world is more endangered today than it has been in my lifetime.”

Former South Carolina Governor Nikki Haley used it to burnish her hawkish credentials when she was running for president. Sens. Tim Scott (R-S.C.) and Marsha Blackburn (R-Tenn.) have also indulged in the fearmongering.

The four states that hawks want to lump together as part of an axis today have some dealings with each other, but their security relationships are quite weak. None of them is formally allied to Russia, and Russia and China have no obligations to come to Iran’s aid. All four governments are run by intensely nationalistic leaders, and they nurse grievances over past humiliations and conflicts that make closer ties difficult to establish.

Russia has turned to Iran and North Korea for arms supplies to wage war in Ukraine, but that has really been the extent of their closer security ties. Of the four countries, only China and North Korea have a formal defense treaty, but despite that, China and North Korea have a fraught relationship. Notably, China has refrained from offering Russia lethal aid in its war in Ukraine. The “no limits” partnership that the two countries announced just before the February 2022 Russian invasion has been distinguished by how limited Chinese support for Russia has been. This is hardly a global alliance in the making.

The danger of basing U.S. foreign policy on imaginary things should be obvious. If U.S. policymakers believe that Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea form an axis when they don’t, that will distort U.S. policies toward all four states in destructive ways. Instead of identifying the best ways to address U.S. disputes with each country, including the use of diplomatic engagement and sanctions relief where appropriate, there will be a strong temptation to see every problem with each state as part of a global rivalry where there will be no room for compromise and reducing tensions.

The more that officials in Washington see these states as a hostile coalition, the less inclined they will be to negotiate with any of them for fear of signaling “weakness” to the rest.

Another pitfall of believing that these states form an axis is that it will undermine Washington’s ability to set priorities and devise a realistic strategy to secure U.S. interests. Once policymakers are convinced that all four states are linked together as part of an axis, they will refuse to distinguish between vital and peripheral interests, and they will insist that the U.S. must “counter” the imaginary axis in every corner of the globe. It will exacerbate Washington’s bad habits of overcommitment and overinvestment in less important regions.

Linking Russia, China, and Iran together as part of an axis has become a favorite rhetorical move for some Iran hawks in Washington. Mike Doran of the Hudson Institute, for example, tried using this to agitate for a more aggressive policy against Iran just recently:

“Iran is the weak link in the Russia-Iran-China axis. The U.S. should press hard on that weakness rather than trying to maintain the status quo. Moscow and Beijing would certainly take notice. The fastest way to bring Putin to the negotiating table is to weaken his ally, Iran. Why are our foreign policy elites unable to recognize such an obvious strategic option?”

There are a few flaws with this plan: the axis in question doesn’t exist; Russia and China would have no problem if the U.S. wanted to waste its resources in yet another costly Middle Eastern conflict; Russia and Iran aren’t really allies; and weakening Iran wouldn’t matter to the Russian government. If the U.S. mistakenly assumes that it can inflict damage on one authoritarian state by undermining the others, it will squander resources and opportunities for engagement in exchange for nothing.

To the extent that these four states are working more closely than they have in the past, aggressive U.S. policies have encouraged that collaboration. The U.S. pursuit of dominance in every region creates incentives for regional powers to assist each other, and Washington’s frequent use of sanctions to punish all these states gives them another reason to help each other evade sanctions.

The correct U.S. approach to increasing cooperation among these states is to exploit existing divisions and to reach a modus vivendi with as many of them as possible to drive wedges between them.

- Setting the record straight on the teeming media swamp that supported Iraq ›

- Russia and Iran: time to dust off the old 'Axis of Evil' ›