In the New Yorker this week, journalist Keith Gessen wrote a piece disentangling what he called “the painful and knotty arguments” over whether and when Washington should pursue negotiations in Ukraine.

He uses the example of Samuel Charap, a researcher at the RAND corporation — who has made the case for the United States to seek an endgame to the war — to explore the calls from a small group of experts in Washington, who, in Gessen’s formulation “argue that there might be a way to end the war sooner rather than later by freezing the conflict in place, and working to secure and rebuild the large part of Ukraine that is not under Russian occupation”

The piece answers what the author sees as the four key questions about when and whether diplomacy can be successful, analyzing the debates over nature of negotiations, the military outlook for the foreseeable future, Vladimir Putin’s ultimate intentions, and, as Gessen put it on Twitter, if there is “any acceptable solution, even a temporary one, that leaves parts of Ukraine occupied by Russian forces?”

On the first question, Charap offered his thoughts on what diplomacy looks like, and what it hopes to achieve. “Diplomacy is not the opposite of coercion,” he told the New Yorker. “It’s a tool for achieving the same objectives as you would using coercive means. Many negotiations to end wars have taken place at the same time as the war’s most fierce fighting.”

Charles Kupchan, a fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, who has also argued that Washington needs a plan to get to the negotiating table, is quoted in Gessen’s piece describing what the initial stages of such diplomacy at the conclusion of the current counteroffensive could look like.

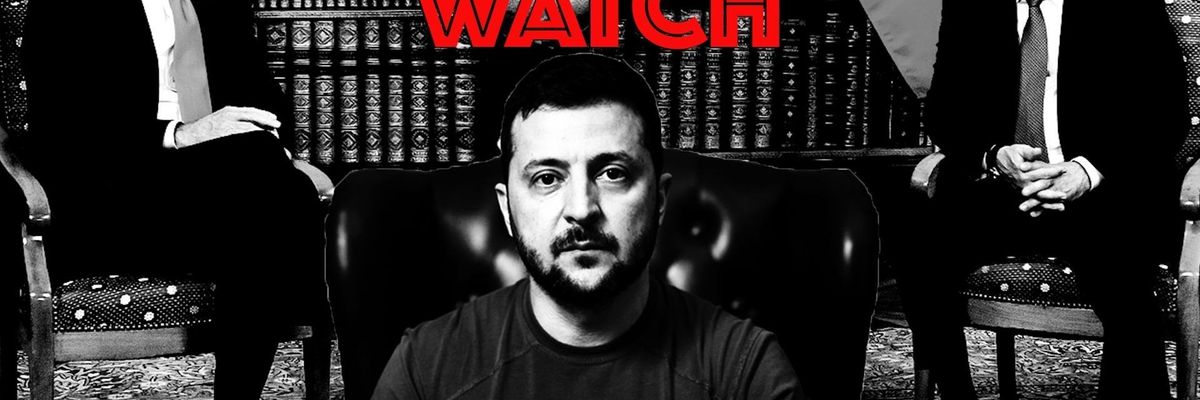

“I wouldn’t say, ‘You [referring to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky] do this or we’re going to turn off the spigot.’ But you sit down and you have a searching conversation about where the war is going and what’s in the best interest of Ukraine, and you see what comes out of that discussion.”

On Thursday, the New York Times released a podcast titled “Is it Time to Negotiate with Putin?,” which seeks to answer similar questions, and comes to the conclusion that the war will not end with a decisive victory for either side.

“We’ve sort of moved well out of the kind of the fairy tale stage of this conflict,” said New York Times opinion columnist Lydia Polgreen, who added that it was time for a new frame for discussions. She also noted that there were other countries with an interest in this war, and their views may contrast with those in Washington and Kyiv. “You have a lot of different power centers, or emerging or aspiring power centers in the world seeing this conflict through lots of different lenses, you know, and jockeying for their own interests,” she said. “And this kind of no negotiation at all position that the Ukrainians have is, I think, increasingly running up against this multiplicity of interests that are pressing on lots of different pressure points around the globe.”

Part of what seems to be animating these assessments is the realization that Kyiv’s counteroffensive will not end in an overwhelming win, and that, as a result, the alternative is a protracted war in Ukraine.

In mid-August, Politico’s NatSec daily newsletter reported that a growing number of U.S. officials are wondering whether Gen. Mark Milley, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, was right when he called for the beginning of negotiations with Russia last November, when Ukraine had clear momentum on the battlefield.

“Most people now recognize that Plan A isn’t working. But that doesn’t mean they’re prepared to discuss Plan B,” Charap says in the New Yorker story. For him, what that Plan B should be is clear: “It would be a diplomatic strategy.”

In other diplomatic news related to the war in Ukraine:

—For the second time since Russia left the Black Sea grain deal in July, a ship safely left Ukraine through a temporary humanitarian corridor. The ship, which departed from the port of Odessa last weekend, was carrying steel bound for Africa. Meanwhile, the Turkish and Russian foreign ministers met on Thursday to discuss possibilities for reviving the deal, but the talks ended without any meaningful progress according to the New York Times.

The meeting was reportedly a preparatory meeting for a future summit between the two countries’ leaders, though a date has not yet been set. The Times says that the discussion was centered around “a plan that [Moscow] casts as an alternative to the deal, one that appears aimed at helping its own exports. (...) In its proposal, Russia says it envisions sending one million tons of grain to Turkey — at a price subsidized by Qatar — that would then be transported to countries that need it.”

—The Wall Street Journal reports that “The Biden administration and its European allies are laying plans for long-term military assistance to Ukraine to ensure Russia won’t be able to win on the battlefield and persuade the Kremlin that Western support for Kyiv won’t waver.” According to the report, Western officials are seeking ways to make pledges for Ukraine’s defense more permanent in case Donald Trump or another candidate who is skeptical of sending more aid is elected president of the United States in 2024.

—The Quincy Institute’s Anatol Lieven wrote in the Guardian this week about Russian public opinion over the war in Ukraine and the prospect of future negotiations. “From conversations I’ve had, it appears that a large majority of elite and ordinary Russians would accept a ceasefire along the present battle lines and would not mount any challenge if Putin proposed or agreed to such a ceasefire and presented it as a sufficient Russian victory,” Lieven writes. “The general elite aversion to pursuing total victory in Ukraine is however not the same thing as a willingness to accept Russian defeat – which is all that the Ukrainian and US governments are presently offering. Nobody with whom I have spoken within the Moscow elite, and very few indeed in the wider population, has said that Russia should surrender Crimea and the eastern Donbas.”

U.S. State Department news:

The State Department did not hold its regular press briefing this week.