There’s a line in the classic 1962 film Lawrence of Arabia where the Arabian prince Faisal, played by Alec Guinness, tells British officer T.E. Lawrence (Peter O’Toole), “The British have a love of desolate places…I think they hunger for Arabia.”

The exchange comes to mind while thinking about “The Great Game,” a historical account written by the late journalist and author Peter Hopkirk chronicling the 19th century rivalry between the British and Russian empires over influence in Central Asia and the surrounding region. It was a contest for new markets, territories, and prestige, whose dramas unfolded as far west as Crimea, to Japan in the east.

For Britain, the chief aim of the game was to protect its colonial jewel in India. For Tsarist Russia, it was the expansion of its imperial reach to match its European rivals, stretching mostly into the Caucasus, Central Asia, and the Chinese borderland.

It was a story greater than fiction, filled with political intrigue, espionage, warfare, and treachery that would make the gangsters of Hollywood movies blush. Hopkirk, a long-time correspondent for The Times of London who developed a fascination for Central Asia as a youth (having read Rudyard Kipling’s novel Kim), tells the tale with the skill of a novelist. His cast of characters includes soldiers and spies, diplomats and politicians, emperors and monarchs, and the kings and khans of greater Asia.

It’s a book published more than 30 years ago, about events more than a century ago, but whose echoes are heard in today’s headlines as old imperial rivalries renew themselves in Ukraine and elsewhere. The Great Game continues in new forms, as the U.S. replaces Britain and Russia reasserts faded ambitions in neighboring lands. Once again, East and West battle for influence on the international stage, the price borne by the peoples of smaller nations. Today it’s Ukrainians, in the days of the Great Game it was Afghans and what are today’s Uzbeks and Tajiks, Turkmen, Georgians, and more.

After a prologue introducing the origins of “the Great Game” (and the phrase itself, coined by Captain Arthur Conolly — later popularized by Kipling), Hopkirk traces Russian security concerns back to the 13th century Mongol invasion of then-Muscovite Russia. Hopkirk’s main story begins with an anecdote about Tsar Peter the Great on his deathbed. In a possibly apochryphal remark, he laid out Russia’s destiny for world domination, from Constantinople to India, and possibly beyond. It’s an entertaining tale, reports of which managed to reach ears in London, stirring paranoia within the British government and a determination to contain Russian expansion in all directions, and particularly toward India.

The desire to protect British interests in India from Russian encroachment would especially trouble neighboring Afghanistan. The British saw the kingdom as a buffer state between India and the Russians and sought to make it at least a neutral neighbor, if not gain outright control.

Hopkirk largely organizes his account chronologically, each chapter telling a story in succession as in an epic 19th century novel or a mini-series, fitting into an overarching narrative. He dates the beginning of the game to the Napoleonic wars and the French emperor’s flirtation with an Indian invasion. This threat, combined with Russian moves southwards into the Caucasus and nearby khanates, stoked the fears of British officials in Calcutta and London. They viewed the region as a strategic gateway into northern India by various mountain passes and overland routes through which armies and equipment could move in an invasion.

As Hopkirk points out, given the difficulties of navigating these mountainous entries into India via Afghanistan or China, the threat of a Russian incursion was greatly exaggerated. It was effectively a red herring to distract the British, while the Russians pursued interests westwards on Ottoman turf. Nevertheless, British diplomatic and military maneuvers were undertaken to gain influence over neighboring powers, such as the Ottoman sultans or the shahs of Persia as safeguards.

Hopkirk also emphasizes the two camps of strategic thinking that emerged within Whitehall to contain the Russians — the “forward” school and the “masterly inactivity” school. The first favored aggression, like later invasions of Afghanistan. The second advocated restraint, opting for diplomacy and covert operations to protect British interests. Agents were dispatched to map the uncharted lands of Central Asia and make overtures to the rulers of ancient cities, including Merv, Khiva, and Bokhara, names that had largely faded from European memory since the days of the old Silk Road.

One of these Great Game “players” included British officer Alexander Burnes, who achieved celebrity status after adventures trekking across the mountains and deserts between India and Persia, gaining the ear of rulers from Lahore to Bokhara. “Bokhara Burnes,” as he became known, reached his ultimate fate in Kabul, Afghanistan.

“There were peaches, plums, apricots, pears, apples, quinces, cherries, walnuts, mulberries, pomegranates, and vines, all growing in one garden,” he wrote after first visiting the city in 1832. His mission was to forge an alliance with the ruling Afghan emir Dost Mohammed, a dangerous one considering the country’s fractured tribal politics and tense relations with pro-British neighbors. Russian eyes also monitored events in Kabul in hopes of establishing relations with Dost Mohammed when it suited both.

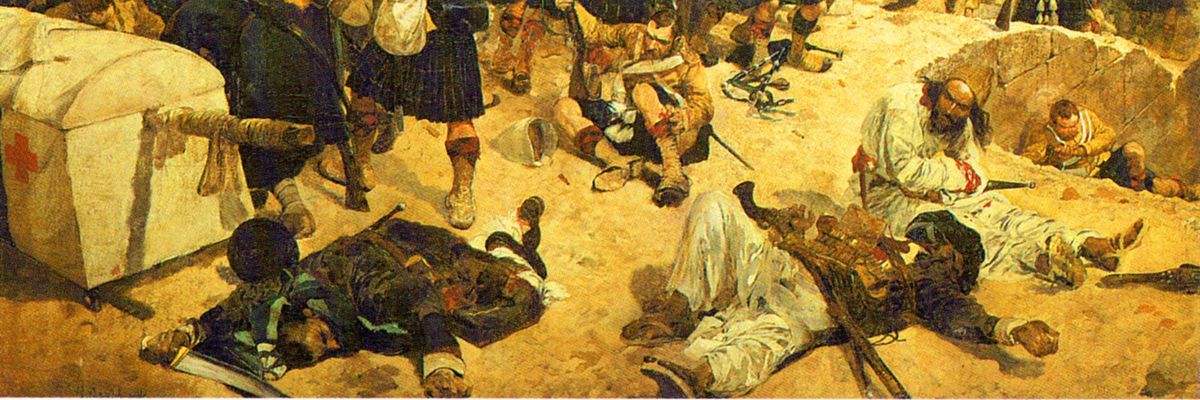

All this eventually drove Burnes and the British to intervene more deeply in Afghanistan. Dost Mohammed, who had befriended the charismatic Burnes, was forced into exile, and the feuding Afghan tribes rose up against Britain’s newly installed puppet ruler. A British invasion followed, and Burnes was brutally killed in a climactic clash as Afghan rebels stormed the capital fortress and his nearby lodging.

The fate of “Bokhara Burnes” would be that of many Great Game players and marked a symbolic failure of the first Anglo-Afghan war (1839-1842). Two more British invasions followed and failed against the fiercely independent Afghans.

There were leading men on the Russian side as well. Captain Nikolai Muraviev undertook a mission in 1819 to establish commercial ties with the Khanate of Khiva. Muraviev had distinguished himself earlier as a 17-year-old ensign during the Napoleonic Wars and later undertook secret missions in Persia disguised as a Muslim pilgrim. After a dangerous journey across the Karakum desert, he arrived in Khiva where he waited in suspense before entering the Khan’s presence in a scene of delightful drama.

Seated on a Persian rug, the reputed tyrant commands his visitor to “speak now” after a momentary quiet. Muraviev then laid out the Tsar’s wish for friendly relations with the Khan, a proposition met with suspicion after the failed Russian invasion of Khiva a century earlier. Muraviev also witnessed Russian slaves in Khivan captivity. Moved by their plight, the officer sensed a potential pretext for a Russian intervention to rescue the captives, with the ultimate aim of seizing the Khanate.

It’s a strategic pattern repeated throughout Central Asia as the Russian Empire expanded. Other personalities of the era included Russian General Kaufman, the “Lion of Tashkent” who oversaw much of the extension of the Tsarist domain throughout the Caucasus and neighboring region as khanate after khanate was overrun.

There were those who matched wits with the British and Russian giants, such as the cunning Yakub Beg, who carved out his own corner of what was then “Chinese Turkestan” on the western borders of today’s China.

What emerges from these distant battlefields are the echoes of history, as seen in the present Ukraine conflict. Largely a covert struggle, the Great Game’s crises were usually resolved through backroom deals between London and St. Petersburg. A notable exception was the Crimean War of 1853, as Britain and its European allies tried to block Russian encroachment westwards. 21st-century Crimea reemerged as a flashpoint between Russia and the West, reminding us that history likes to rhyme.

A treaty in 1907 formally “ended” the Great Game between Britain and Russia, as a new imperial rival emerged in unified Germany. The game’s successors in the 20th century were the United States and Soviet Union, on an even greater stage spanning multiple continents, with greater stakes as the clouds of nuclear war loomed overhead. Like their British predecessors, both attempted to conquer Afghanistan and failed. The Afghans learned in those centuries and ours, as did many others, what the meaning of “friendship” with these imperial powers was.

The players of the Great Game were daringly ambitious, if not foolhardy. They remained largely anonymous, without a monument to their name, as Hopkirk concludes: “Today they live on only in unread memoirs, the occasional place name, and in the yellowing intelligence reports of that long-forgotten adventure.”