In February of 1913, the editors of the Standard issued a stark warning to their readers: Great Britain was being besieged by mysterious flying objects, and it was well past time to do something.

“There is not the smallest doubt but that this country at the present moment is the object of a systematic aerial reconnaissance carried out at night,” they wrote. The culprit? “There is only one answer to that question [...] Germany alone possesses aircraft capable of doing what is being done by the airships that have been seen over England.”

The journalists, like many of their compatriots, were caught up in the Phantom Airship Panic of 1913. Over the course of several months, thousands of Britons claimed to have seen Zeppelins flying overhead, stoking fears that Germany was surveilling the British Isles — and perhaps even threatening to strike them from above.

The episode may sound familiar. Today, the United States is in the throes of its own panic, which started when an apparent Chinese spy balloon flew over the country earlier this month. Politicians and journalists quickly seized on the story, with some speculating that the balloon could be far more than a surveillance threat. “How do we know the next balloon isn't loaded up with bioweapons?” asked Jesse Waters of Fox News.

The Balloon Panic of 2023 continues to drag on, with reports of new flying objects being spotted — and shot down — for three consecutive days last week. In hopes of finding some lessons for our current crisis, RS spoke over email with historian Brett Holman, author of a 2016 journal article entitled “The Phantom Airship Panic of 1913: Imagining Aerial Warfare in Britain before the Great War.”

The following conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

RS: To start off, can you summarize the Phantom Airship Panic of 1913? Do we know what they were actually seeing?

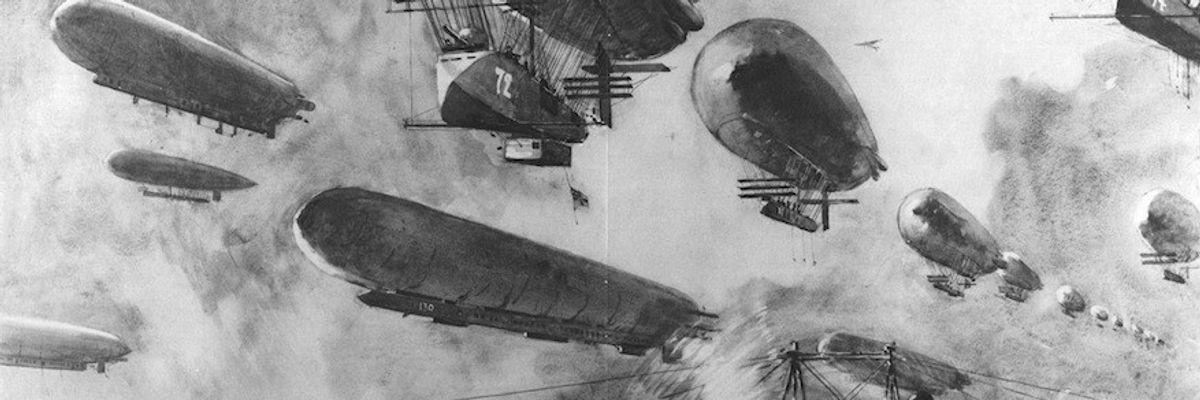

Holman: For several months in early 1913, thousands of people right across the breadth of the United Kingdom reported seeing hundreds of airships in the skies above where there shouldn’t have been any. This was still very early in the era of flight, and aircraft were still quite rare. Airships were rarer still; the British military, for example, only possessed three small airships, with only a couple in private hands.

The obvious explanation seemed to be that the airships were German Zeppelins, since these were by far the most advanced airships in existence, enormous machines capable of flying hundreds of miles from their bases and back. And, of course, from 1915 Zeppelins did bomb London and other British cities. But Germany denied responsibility for the phantom airships, and no records have ever been found to support the idea that Zeppelins carried out such overflights in peacetime, especially on such a massive scale. We can’t be sure what it was that people were actually seeing, but hoaxes, searchlights, geese, and the planet Venus were all put forward as alternative explanations at the time.

What drove popular British fears about the phantom dirigibles?

Holman: One factor was a longstanding concern about German intentions towards Britain. Rivalry between the two empires had been increasing since the turn of the century, most famously in terms of battleship construction, which some in Britain feared was aimed at overturning the Royal Navy’s dominance of the seas and possibly opening the country to German invasion. Some people assumed that Germany was hostile to Britain, and so it was easy to believe that it might send aerial spies over the North Sea.

The other factor was the coming of flight. This was widely predicted to be a new factor in warfare, but nobody knew how it might change the balance of power, especially at sea. From the British point of view, the German navy seemed to be putting a lot of effort into its Zeppelin fleet, which could be used to spy on British warships and dockyards, or even to bomb them at the outbreak of war. A lot of the discussion in the British press about the phantom airships centred on the idea that they were German preparations for a future war, testing out the feasibility of making long distance flights over Britain at night or perhaps spying on British fortifications from above, identifying potential targets for bombing or sabotage. Britain’s air force was very small and it had no large, long-range airships, so suddenly it seemed like the nation might be vulnerable from the air.

RS: You note in your article that some journalists and politicians tried to harness the panic around the phantom airships to increase support for a greater military build-up. One newspaper editor even wrote that "without being thoroughly scared, the great British public will not bring pressure to bear on the Treasury" to expand airplane and airship manufacturing. Generally speaking, how did journalists and politicians approach the panic?

Holman: The British press before the First World War was politically quite divided, with most supporting one of the major parties, the governing Liberal party or the opposition Conservatives. The Conservative press largely fanned the panic, looking for evidence of German involvement, pointing to reports of Zeppelin construction and flights, scoffing at denials from Berlin. Even when they were sceptical of the existence of the phantom airships themselves, they could still point to the keen German interest in building up an air force and contrast that with the apparent lack of progress in building up British military aviation. In other words, the phantom airships were a useful stick with which to beat the Liberal government. (The quote by the editor reflects the experience of the 1909 dreadnought panic, when the government was essentially forced by press hysteria to build eight battleships, a template which was more or less openly followed by some Conservative newspapers in 1913.)

Liberal newspapers, of course, were more likely to defend the government, urge caution in blaming Germany, and to scoff at the phantom airships generally, linking them to Germanophobia or spy hysteria. Liberal newspapers often suggested that the phantom airships were in fact secret British military or civilian projects. In other words, the phantom airships were nothing to worry about.

RS: How did the panic end?

Holman: The panic eventually collapsed under the weight of its own absurdity. There were just too many sightings, at too many places, widely separated in distance but close together in time, that it became impossible to believe that even the German Zeppelin fleet could be responsible for any but a tiny fraction of them. And if some of the sightings weren’t real, maybe none of them were. All of a sudden, the press lost interest in the phantom airships. Some sightings were still being made, but even the most persistent promoters of the panic had moved.

RS: As you've likely seen, the United States has recently been in the grips of its own panic over a series of balloons and other unidentified aircraft that the American military has shot down in recent days. Speculation around the nature of the balloons has been rampant, with some politicians claiming that President Joe Biden's slow response is a sign that he is weak on China. Rumors of alien involvement have also grown so popular that the White House had to state that there is "no indication of aliens or extraterrestrial activity with these recent takedowns." How does this moment compare to the 1913 panic?

Holman: There are some big differences. The balloons shot down by the US military in 2023 are in fact real, unlike the phantom airships. At least one of them was acknowledged by the Chinese government, though claimed to be civilian and harmless; in 1913 the German government, credibly, denied all knowledge of the phantom airships. Finally, the phantom airships were a mass phenomenon, seen and reported by ordinary people; the spy balloons are tracked on radar and seen only by military pilots. As far as I know, there hasn’t been a spate of people reporting phantom balloons this time around.

Airships, especially Zeppelins, were highly advanced technology in 1913 – so advanced that Britain, the closest thing to a superpower that then existed, could not build a credible airship fleet of its own. In 2023, as many commentators have noted, balloons are hardly cutting edge; in fact, they are the oldest form of human flight, 240 years old this year. And for surveillance they seem completely outclassed by satellites. There are some advantages balloons possess in terms of loiter ability, and they are more steerable than they used to be, especially at stratospheric heights. But I don’t think it can be argued that anxiety about balloon espionage has been building over the last few years. If anything, I would have expected a drone panic instead.

But there are some common features. There is the panic over a foreign threat being whipped up by the press. This taps into existing anxieties of unforeseen dangers which can upset the status quo, perhaps particularly worrying for a dominant power like Britain before the First World War or the United States today. In domestic political terms, these panics are useful for those who want to argue for defensive and offensive action, but also, and maybe mostly, who want to attack the government of the day.

Stepping back a little, it seems like the particular form of the panic doesn’t matter too much, whether it’s airships or balloons. It’s the sky itself which is the threat vector. It’s above us at all times. We can’t escape it, we can’t keep it away. And that’s usually not a problem. But it’s always there as a potential way for enemies to reach us, and when we are anxious about outsiders the sky can become a screen to project those anxieties onto.

RS: Notably, Chinese balloons have also been spotted over Latin America and the Middle East, according to the U.S., but reactions in those regions have been much less emphatic. What is behind this split reaction in your view?

Holman: This is a good place to point out that Britain wasn’t the only country where mysterious things were seen in the sky in the early years of flight. There were particularly intense waves of sightings in the United States in 1896 and 1897, Australia and New Zealand in 1909 and 1918, Canada and the United States (and Britain again) in the early years of the First World War, Scandinavia in the 1930s, Europe in 1946. What’s interesting about this is that what people saw tracked the latest aeronautical technology (airships, then aeroplanes, then rockets) and that they weren’t always seen as something threatening. The scattered mystery airships seen in Australia in 1909 were sometimes thought to be, rather optimistically, evidence that Australian inventors were going to put the nation at the forefront of the aerial age. But in 1918, the mystery aeroplane sightings that swept south-eastern Australia were interpreted almost universally as being flown by German spies. That clearly reflects a big change in the international situation, from peace to war. So the split reaction to mystery aircraft, then as now, comes down to how threatened people in those countries feel by foreign powers; and, for that matter, whether they think they have more important things to worry about.