Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, is 83 years old. And while he has lived long enough to see the 44th anniversary of the Iranian Revolution, the struggle to succeed him cannot be far off. Indeed, it has already begun. All the key parties, not least of which is the radical clerical establishment, are now maneuvering to back their favorite candidates and to define the political or religious criteria for a new rahbar, or supreme leader. The contest has become especially heated against the backdrop of a popular revolt that began in September 2022, when Iran’s “morality police” beat a young woman to death after arresting her for failing to wear “properly Islamic” dress. Although the regime has managed to quell the protests, the emergence of a very public debate over the hijab, the wearing of which the Iranian regime has long made mandatory for women, has become inextricably bound to the succession struggle. All the contestants are now using this debate to signal their stance on how the Islamic Republic might be reinvented and what role the leader should play in this process.

The trickiest dimension of this challenge concerns the very role of Islam in the Islamic Republic. Who is the ultimate authority when it comes to defining this role: the leader, the semi-official clerical establishment, or perhaps the people, via the closely controlled electoral system? The regime’s unrelenting brutality has put these questions front and center. Indeed, the security forces’ assault on young people, including children, has prompted condemnation from some of Iran’s leading clerics. These critiques suggest that the Council of Experts—which is technically responsible for choosing a new leader when the time arrives—will not have an easy time corralling some clerics who, with good reason, might attribute their increasing isolation from Iran’s younger generation to the repressive legacy bequeathed by Khamenei himself. Several of these clerics, not to mention some veteran conservative politicians, are pushing back against the idea that the state should be using force to elicit “proper” Islamic social behavior.

Iran’s radical clerics are resisting these calls to distance mosque and state. But because they are widely despised, these clerics—and Khamenei himself—are now more reliant than ever before on the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and other security forces. If Khamenei’s successor follows in this path, the array of competing institutions that once provided a contested but still important bridge between the regime and the wider populace will be denuded of any power or authority. Thus the unfolding succession struggle could set the stage for the emergence of a fully militarized regime whose reliance on brute force will provide neither stability nor security.

The Leader and the Clerics

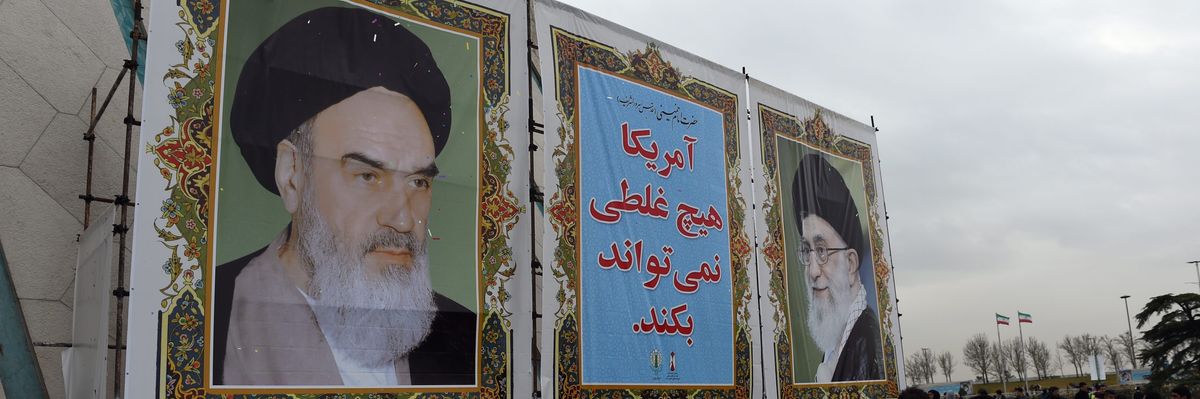

Although reinventing the system may be harder today than ever before, Iran’s leaders have been tussling over the ideological and institutional parameters of the Islamic Republic system for more than four decades. Some of these struggles have produced significant shifts in the rules of the political game. For example, the succession contest waged in the months prior to former Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s death in June 1989 precipitated several changes. These included a revision of the constitution that allowed his successor to become the rahbar even though Khamenei had not yet earned the lofty religious position of “marja-i taqlid,” or “source of emulation.” In effect, Khamenei presided over a quasi separation of mosque and state, with himself as the final arbiter of the political system whose authority, as the country’s constitution states, rests first and foremost on his “political perspicacity.”

Khamenei used his enhanced political power to expand the financial and institutional reach of the Office of the Supreme Leader, thus securing his position as the ultimate political arbiter. But if this dynamic worked to his favor, it also prompted inconvenient questions about his religious authority, especially when his actions provoked consternation in some leading seminaries. Indeed, such concerns emerged in 2009, when the regime used an iron fist against tens of thousands of demonstrators who had taken to the streets of Tehran to protest what they claimed was widespread fraud in that year’s presidential election. Shocked by this violence, not only did some veteran clerics question the validity of the electoral results, but as subsequent research has shown, some even went so far as to suggest that the regime’s brutality contravened Islamic law.

The turmoil of 2009 turned out to be a dress rehearsal for the far more extensive battle between state and populace that has been unfolding since September 2022. But what sets this current struggle apart is not only its greater duration and national scope. What gives it enormous political and symbolic meaning is the fact that protests against the enforcement of “Islamic” dress codes echo a fundamental debate regarding what it means to have an “Islamic Republic.”

Khamenei’s Rhetorical Game Falls Short

This debate is hardly a theocratic or theoretical matter. On the contrary, it is deeply political because the Iranian Constitution gives the supreme leader ample power to define (or redefine) the system’s political rule book. It is precisely the uncertainty of what a new leader might say and do that is driving a strikingly open discussion regarding the succession issue. The chance to test the political waters, as it were, has in fact never been better; with the issue of the hijab now front and center, rival parties in the succession game are using the controversy to make a wider case for the particular kind of Islamic system that they favor, and the candidate they want to realize that vision.

Khamenei set the tone for this debate when, in early January, he argued that “hijab is an inviolable Sharia necessity,” yet also stated that “those who do not fully observe the hijab should not be accused of irreligion.” And his cautioning of his supporters to “avoid excluding those with poor hijab from Islamic and revolutionary circles” seemed to signal his concern that the unbridled campaign by the country’s morality police would inadvertently widen the circle of opposition to the regime and to Khamenei himself. But even though he projected these concerns, it is difficult to believe that Khamenei—who many protestors openly condemned during the fall 2022 demonstrations—seriously thinks that he can or should dissociate himself from the actions of his hardline allies. On the contrary, his January appointment of General Ahmad Reza Radan—a veteran security actor who presided over the 2009 crackdown in Tehran and who has been a zealous advocate of “Islamic” dress codes—as Chief of Police suggests that Khamenei is determined to fully embrace hardliners in the security apparatus and among the clergy, who are, after all, his natural allies.

Hardline Clerics Plant Their Flag

This embrace comes against the background of the unusually public discussion regarding the rahbar succession issue that surfaced in Iran’s semi-official media in early fall. This politically sensitive discussion has apparently spooked the Council of Experts. Council Spokesperson Ahmad Khatami insisted that the various names that had been floated were only rumors, and held that it was the exclusive task of the council to address the issue of succession. Its deliberations, he suggested, would be limited to a smaller group from within the 60 plus members of the council itself. Fellow council member Mohsen Araki backed this claim, while another colleague argued that although it is not the task of the council to select the leader, it is still its job to “determine the criteria for choosing the next leader.”

For these hardline clerics, the most important of these criteria is not religious training or status; rather, it is a readiness to use whatever means necessary to crush all opposition. Joined by other clerics, Araki underscored this cold-blooded political message in December when he asserted that protesters were guilty of “corruption on earth” and were engaged in moharebeh (waging war against God), and on that basis should be executed. These clerics thus used the protests to draw a line in the sand that no one could ignore. Even if Khamenei wanted to foster conciliation (which is unlikely), his interest lies in sustaining his alliance with these hardliner clerics because in doing so he is not only establishing the ideological bottom line for the next rahbar, but is also defending a ruling institution that has enormous financial and coercive resources that hardliners are determined to protect.

Dissension in the Ranks

Yet even as they maneuver to protect the Office of the Supreme Leader, Khamenei’s allies have not been able to silence criticisms of the regime’s violence that have wider implications for the succession question. This debate has been spearheaded by several prominent clerics, including Ayatollah Mohammad Ali Ayazi. He argues that the regime has misused the concept of “moharebeh” in ways that run contrary to Islamic jurisprudence. In effect, Ayazi has accused the regime of manipulating Islamic law to justify the unlawful killing of its opponents. Other religious leaders, including Ayatollah Morteza Moqtadaie—a former prosecutor general who backed the 2009 crackdown—have mirrored this critique. And because Moqtadaie is also a member of the Council of Experts, his words suggest dissension within the ranks of the council itself. That this dissension is coming from clerics whose hardline credentials are beyond reproach could give their criticisms political and moral weight.

Still, it is far from clear that this discord will ultimately shape the simmering succession struggle. The key challenge for the decision makers who are now engaged in this contentious process is not to impose what will ultimately be a fake consensus among rival clerics. Rather, it is to find a new leader who can guarantee regime survival, but in ways that might reconstitute a modicum of practical legitimacy for Iran’s rulers. Beyond balancing these potentially conflicting priorities, any serious contender to the position of rahbar must also secure the backing of the IRGC. In the coming months its commanders will exercise enormous influence over the inner circle of clerics who are ostensibly running the rahbar search.

Rahbar Succession Games

So far, two names for potential successors have repeatedly surfaced: Mojtaba Khamenei (Ali Khamenei’s son) and President Ebrahim Raisi. Both are long-standing members of an ideologically zealous hardline elite whose world view crystalized during Iran’s 8-year war with Iraq. Beyond their shared commitment to defending the Islamic Republic at home and abroad, both are clerics who have repeatedly advocated the repression of all dissent. Indeed, Mojtaba Khamenei backed the 2009 crackdown and was in fact accused by many reformists of playing a key role in rigging the presidential election on behalf of then President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and his powerful ally at the time, Supreme Leader Khamenei. Still, he brings liabilities that could also undermine his candidacy. The greatest of these is his own father since the idea of a kind of royal dynasty runs counter to the populist concept of Islamic rule that Khomeini and Khamenei both advocated. The very possibility of Mojtaba Khamenei following in his father’s footsteps would probably spark resistance from within the IRGC and from high-ranking clerics, many of whom apparently believe that he lacks the minimal religious qualifications to be the rahbar. Moreover, while skilled in the dark arts of repression, he lacks the political experience, talents, and even the nuance of his father.

By contrast, while Raisi’s religious credentials may not be vastly superior to those of Mojtaba Khamenei, he has one crucial advantage: he spent his career rising through the ranks of the judicial system. This path led him to join the Popular Front of Islamic Revolution Forces political organization in 2016, only to lose his challenge to then incumbent President Hassan Rouhani during the 2017 presidential election. Buoyed by the declining fortunes of the Reformists and by his close alliance with Khamenei, Raisi then took the presidency in 2021. This insider’s political experience is surely attractive to other forces such as the radical clerics, and of course the IRGC. Indeed, having Raisi at the helm might give the IRGC the influence it craves, without exposing it to the risks that it might otherwise suffer if one of its own security members were to secure the position of rahbar (a very unlikely scenario in any case). Having Raisi as the next supreme leader could thus be a win for both parties.

A Securitized System?

While this discussion unfolds, a more elemental question is looming: will the position of the rahbar still matter in a system that is being stripped of the very imperfect mechanisms of elite contestation and limited—but real—electoral competition that once provided a bridge between state and society? A securitized system that is emptied of institutional channels for managing elite and mass conflict will provide neither real security nor stability.

The destabilizing effects of hardliners’ drive for total control has prompted some veteran leaders to begin a process of consultations across the ideological and political divide. One of the leaders of this effort is Iran’s Speaker of Parliament Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf. It may seem paradoxical that a man who has spent his career as a powerful figure in the security apparatus is now making a case for backing away from the abyss of unbridled autocracy. But as his own statements suggest, what Ghalibaf seems to fear most is that the violent repression of protests in the name of an extreme position on issues such as the country’s dress code will further polarize society, thus playing into the hands of those he has labeled “the enemies” of the system. This concern reflects the culturally conservative pragmatism of a diverse group of veteran leaders who are now calling for “reforms.” While Ghalibaf and has allies have avoided defining such reforms more clearly, their efforts suggest that as the succession struggle moves from a simmer to a full boil, they are trying to find a way back to some kind of politics.

Hardliners are firmly pushing back against these efforts. At the same time, however, the succession struggle might not provide the clarity they seek. For if the Council of Experts fails to reach agreement, the constitution stipulates that it can create a temporary “leadership council” of religious figures who will rule until a single candidate is chosen. If this kind of collective ruling system—with all of the uncertainties it entails—lasts for weeks or months, it could prompt the IRGC to impose its favored candidate. Such a move would highlight the failure of Iran’s leaders to find a workable formula for saving the Islamic Republic from lurching toward its own form of despotism.

This article has been republished with permission from Arab Center Washington DC.