Following the United Kingdom’s formal departure from the European Union three years ago, London has prioritized deepening trade and defense ties in the Indo-Pacific, where it wants to be a leading Western actor.

Focused ever more on its own cost-of-living crisis and on providing military and humanitarian support to Ukraine against Russia’s invasion, however, Britain is arguably overstretching itself.

Nonetheless, Washington’s continuing quest for allies to help implement its containment strategy against China in the Indo-Pacific has made London, despite its limited resources, a partner of Washington’s vision.

In a meeting between Anthony Blinken and UK Foreign Secretary James Cleverly on January 17, the two countries’ close cooperation on China was once again raised. Blinken welcomed the UK “deepening its engagement in the Indo-Pacific,” while lauding agreements to increase London and Washington’s “close consultation” on various regional issues, including “maintaining peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait.”

As per its 2021 Integrated Review, London has sought to enhance its trading relations with various countries in the Indo-Pacific. While pushing the idea of “British leadership,” the Review also expressed London’s wish to become the most integrated European partner in the Indo-Pacific by 2030.

While seeking trade with the region is important for Britain — especially after Brexit — China’s rise has introduced another dynamic to the UK’s approach to the region. The Review depicted Beijing as a threat to British security and interests. And, as the Review described the United States as the UK’s most important strategic ally and partner in the region, it indicated an endorsement of Washington’s posture there.

“Both [the UK and the U.S.] have highlighted a level of existential threat [from China] in the battle for the future of democracy and the liberal world order,” according to Sophia Gaston, the director of the British Foreign Policy Group, a London-based non-partisan think tank. She noted that the language used about China in the UK’s Integrated Review largely echoes that of the Biden administration.

Both governments, she added, have a “shared desire to challenge China through forums outside the bilateral relationship, building up capacity in the Western alliance and forging new alliances with liberal nations with a similar interest in China’s rise.”

Blinken and Cleverly’s discussions came a week after Japan and Britain signed a Reciprocal Access Agreement allowing mutual military deployment in each other’s countries and increasing the number of joint exercises in which they engage. Prime Minister Rishi Sunak said the deal, which was first agreed in principle under Boris Johnson’s premiership in May 2022, “cements our commitment to the Indo-Pacific.”

While Tokyo welcomed Britain’s deepening engagement in the Indo-Pacific, with Prime Minister Fumio Kishida arguing that “security in Europe and the Indo-Pacific region are inseparable,” Japan has encouraged the UK’s expansion in the region within Washington’s strategic framework.

London and Tokyo have been working for some time on defense cooperation. In August and September 2021, the UK deployed a new Royal Navy flagship to Japan where it conducted joint exercises with Japanese, U.S., and Dutch navies. Since then, London has also participated in various joint naval patrols, including most recently a U.S.-led exercise in November 2022 with Japan, Canada, and Australia.

London also deployed two permanent vessels in the Pacific following concerns between Japan and the UK about China’s military buildup around the Taiwan Strait. The ships are also near the disputed Senkaku islands that are administered by Tokyo but claimed by China, which refers to them as the Diaoyu Islands.

Yet, while Britain’s Conservative government has aligned itself with Washington’s military strategy in the region, it is also concerned about maintaining its important economic relations with Beijing, an ambivalence that sometimes rises to the surface, notably in parliamentary debates.

Boris Johnson, who led Britain’s tilt to the Indo-Pacific, also presented himself as a “Sinophile,” who welcomed trade with Beijing. Yet, during Johnson’s tenure, his government pledged to remove all Huawei equipment from 5G networks in the UK by 2027, largely as a result of strong pressure from Washington which waged an international campaign to persuade nations that Huawei’s networks could be used by Beijing for espionage.

Under Johnson, Britain also joined the AUKUS defense cooperation pact with the United States and Australia in September 2021, thus further consolidating Britain’s participation in Washington’s containment strategy. Even more dramatically, Johnson’s foreign secretary who later succeeded him briefly as prime minister, Liz Truss, demanded that Britain follow Washington’s lead in curbing certain kinds of trade with China and later urged Western states to boost Taiwan’s defensive capabilities to deter a Chinese invasion.

Sunak, who succeeded Truss, has since announced the development of a new fighter jet called Tempest which will be co-produced by Japan and Italy and begin flying in 2035.

Sunak has said that what David Cameron once described as the “golden era” of UK-China relations is now over. But he has also called for “robust pragmatism” in dealing with China, suggesting that he is juggling pressure for a harder line on Beijing and Beijing’s possible importance in overcoming Britain’s worsening economic situation. After all, China is the largest source of imports to the UK, and these economic ties have only become more critical after Britain’s withdrawal from the EU single market.

“While China's economic model has directly challenged U.S. industry, Britain had de-industrialised long ago and its services economy has, if anything, benefited from China's rise,” David Lawrence, Research Fellow at Chatham House, told Responsible Statecraft.

Despite these differing economic priorities, “Britain’s interest in the Pacific is primarily related to safeguarding the U.S.-led world order and strengthening its post-Brexit relationships in the region,” he added. “However, the UK does not have anywhere near the resources of the U.S. to commit to the region.”

Of course, there is also the issue of Hong Kong, which remains a sore point in relations between Britain and China. As Beijing has eliminated the former British colony’s autonomy and cracked down on dissidents and the pro-democracy movement there in recent years, bilateral relations have been negatively affected.

Despite the importance of Britain’s retention of trade ties with China and the region, London has, for all practical purposes, aligned its regional policy with Washington. With a Royal Navy that has been shrinking for several decades and its already large commitments to Ukraine, the UK is limited in its ability to play a more independent role.

As a November report by Chatham House noted, European states, including the UK, have little choice over whether to align closely with Washington in the Indo-Pacific despite their individual ambitions for the region.

And given domestic pressure to focus on the UK’s economic woes, internal debates over how much Britain can commit to the Indo-Pacific, whether it should prioritize trade over its military alliances, and how it should ultimately engage with China will likely continue, particularly ahead of an anticipated update to the Integrated Review.

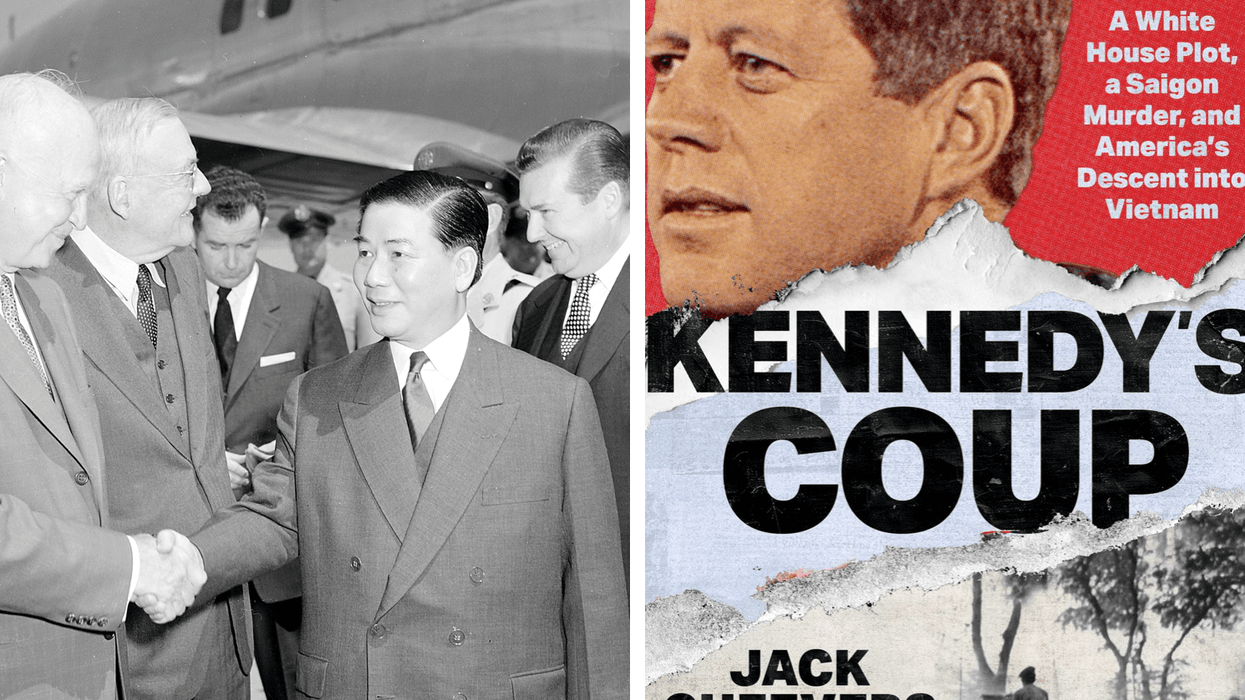

President John F. Kennedy and Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. in 1961. (Robert Knudsen/White House Photo)

President John F. Kennedy and Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. in 1961. (Robert Knudsen/White House Photo)