Something about the subject of U.S. relations with Israel can lead even the most eminent scholars and thinkers to abandon temporarily the skill, insight, and respect for evidence that justifiably earned them their reputations.

Sometimes the trigger for the abandonment is any questioning of the extraordinary form that the U.S. relationship with Israel has taken. Another trigger, which tends to elicit an even more vehement response, is any suggestion that the nature of that relationship results even partly from the work of an Israel lobby within the United States. The precise motivations for the abandonment undoubtedly vary from one individual to another, but it can happen to the best of them.

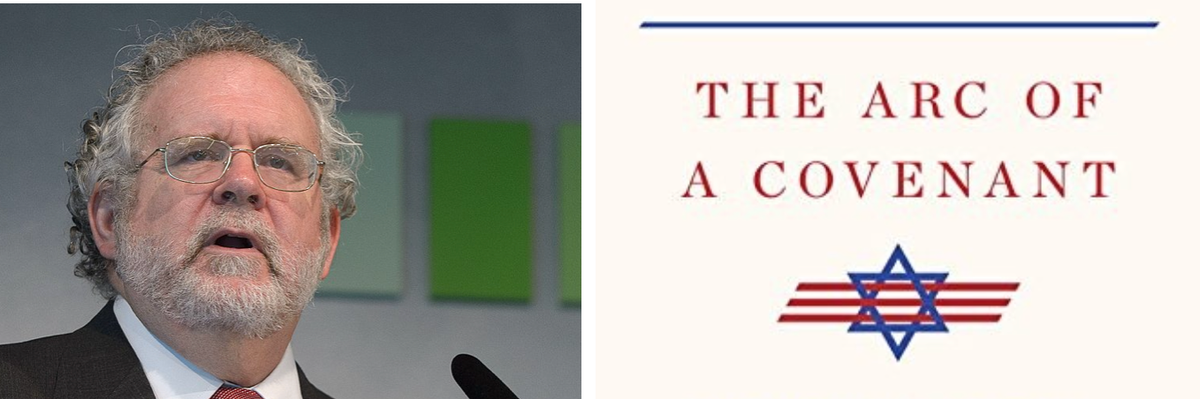

It has happened to Walter Russell Mead, who previously distinguished himself with insightful scholarship about the social and intellectual roots of American political thought and American attitudes toward the outside world. His earlier book “Special Providence,” which analyzes competing traditions in American foreign policy, is deservedly considered a classic. In “The Arc of a Covenant: The United States, Israel, and the Fate of the Jewish People,” Mead’s considerable erudition is still on display. The book contains much rich scholarship on topics that go far — often very far — from the subject that the title promises, ranging from international politics among pre-World War I empires to Cold War strategizing within the United States.

But before he gets to any of that, he states in a couple of introductory chapters his main purpose, which is to discredit the idea that U.S. policy toward Israel has had anything whatever to do with an Israel lobby. He also states another aim, which is a distinct issue from the first one even though Mead constantly conflates the two: to deny that U.S. policy toward Israel is the result of Jewish influence. Mead, the Wall Street Journal’s “Global View” columnist and a Distinguished Fellow at the neoconservative Hudson Institute, writes that he was tempted to subtitle the book “Don’t Blame Israel on the Jews,” which he should have done, because that subtitle would have characterized his mission and message more accurately than the subtitle that was chosen.

Mead’s conflation of those two things is embodied in a supposed school of thought that he posits near the beginning of the book, becomes his bête noire for the rest of the volume, and that he labels “Vulcanism.” (The label comes from one of the many digressions in the book, about a postulated Planet Vulcan that some past astronomers mistakenly believed must exist because of observed perturbations in the orbit of Mercury.) Vulcanists, according to Mead, believe that the insidious political influence of Jews must be responsible for U.S. policy toward Israel because no alternative explanation can account for the shape that policy has taken.

It is hard to identify, however, anyone participating in serious foreign policy discourse in the United States who fits that description. Although American politicians considering policy toward Israel during that state’s early years might have thought primarily about the “Jewish vote,” those days are long gone. The American religious group that is both more numerous than Jews and much more enthusiastic in pushing policies that defer to Israel is Christian evangelicals. That strong pattern comes through in opinion polls. It also appears in politicians’ statements when they are candid about their political motivations — as Donald Trump was when, among the many unilateral gifts he bestowed on Israel, he moved the U.S. Embassy to Jerusalem. “That’s for the evangelicals,” Trump declared.

Mead documents at length this pattern and the developments in American Christian evangelism that have surrounded it, but that does not stop him from continuing to equate the concept of an Israel lobby with a belief in pernicious Jewish influence, making Vulcanism a straw man. One purpose this serves is the purpose that any straw man serves, which is to posit something that is easily disproven. And Mead’s conflation wrongly suggests that, if the belief about heavy Jewish influence is so obviously mistaken, then the whole idea of an Israel lobby must be mistaken too. Another purpose is to give Mead the opportunity to play the antisemitism card against anyone who speaks of an Israel lobby. He usually plays it more subtly and indirectly than many others do, but play it he does.

Notwithstanding how determined Mead is to knock down any idea that an Israel lobby exists and has exerted significant influence on U.S. policy toward Israel, he does not identify his target — people who have written or spoken about this subject — let alone address what they have actually said. For example, John Mearsheimer and Stephen Walt’s taboo-breaking 2007 book on the topic is still probably the most comprehensive scholarly treatment of the subject, but Mead never mentions it — not even in a citation buried in an endnote. Nor does he mention more recent analyses. The one place he identifies and quotes specific contemporary people who appear to match his description of Vulcanists is in the final few pages of the book, and those people are from the loony-bin fringe: right-wing conspiracy theorist Alex Jones and alt-right activist Kyle Chapman.

On the same early page in which Mead acknowledges the importance of engaging opposing ideas, he announces that he will not be doing that. “To engage with every form of Vulcan Theory,” he says, would make for a longer, duller, and less interesting book. But he does not engage with any form of the discourse that addresses the Israel lobby, other than the blatantly antisemitic output of extremists such as Jones and Chapman.

This huge gap — of paying no attention to the content of scholarship and commentary that is Mead’s principal target — underscores another aspect of his Vulcanist straw man, who, in Mead’s description, believes that a Jewish-directed lobby is the sole explanation for why U.S. policy toward Israel looks like it does. No serious commentator believes that.

The dependent variable to be explained is an extraordinary U.S.-Israeli relationship that not only leaves ample room for multiple explanations but demands attention to multiple factors that collectively have pushed U.S. policy in the same direction.

Mead’s book thoroughly describes some of those factors, especially aspects of American history and society that have predisposed many Americans to have a positive attitude toward Israel. This part of his analysis is valid and well-grounded, but it does not follow — although this is what Mead evidently would like the reader to believe — that, given the influence of those historical and social factors, it cannot be true that there exists a lobby that also is exerting influence.

I have written about some of the same factors that Mead has, including a popular perspective dating back to colonial times in which many Americans viewed their nation as the “new Israel,” feeding a sense of commonality first with the Israelites of the Old Testament and later with modern Israel. I did so in a book about how Americans’ national experience has shaped many of their attitudes toward the outside world and with it some aspects of U.S. foreign policy. As a social scientist, I always would like to claim that I have explained most of the variance in a phenomenon, but I never suggested that my explanations about the effects of history and national experience somehow invalidated observations about other factors that also have helped to shape current American attitudes or U.S. policies.

Extraordinary phenomena require explanations that may not be individually extraordinary but, more often, involve a combination of factors that together create the conditions for a perfect storm. The U.S.-Israeli relationship is an extraordinary phenomenon, outside the norm for bilateral relations between sovereign states. It includes, among other extraordinary features: U.S. aid that has totaled more than $150 billion, given in an unending stream to a state that is now among the wealthiest in the world; diplomatic cover for Israel’s treatment of Palestinians, which has brought the United States only isolation and resentment; and gifts to the Israeli government that bring the United States (as distinct from the American politicians that have bestowed them) nothing positive in return. No single cause brought the United States to this extreme state of affairs. It required the collective influence of several factors, including the historically based predispositions about which both Mead and I have written and the work of a powerful lobby.

Mead contends that sound strategic reasons have argued for a U.S. partnership with Israel, but none of the examples he cites argues for the extraordinary nature that the U.S.-Israeli relationship has assumed. What strategic benefits are to be had could be had through a normal, businesslike relationship.

For example, Mead identifies as one supposed benefit counterterrorist cooperation with Israel, including exchange of information about terrorist groups of common concern. But whatever Israel is doing along these lines, it has its own reasons for doing, special relationship or no special relationship. This is one form of cooperation in which states do not even need to be allies to have good reason to cooperate, as long as the terrorist groups involved are of concern to each side. When I was a counterterrorist officer in the U.S. government, I was involved in counterterrorist cooperation, including exchanges of information, with some states that were not allies and on most issues were even considered adversaries of the United States.

Moreover, the extremely close association of the United States with Israel has led many Middle Eastern terrorists and other radicals — as General David Petraeus, among others, has observed — to apply to the United States the hatred they have for Israel because of its treatment of the Palestinians. Given this factor, the close association is almost certainly a net negative for the United States as far as counterterrorism is concerned.

Mead dusts off some familiar but vacuous talking points (dare we call them tropes?) that others have voiced in trying to deny the existence of a powerful Israel lobby. One is to say that any such lobby can’t be very powerful because one can cite examples when U.S. policy did not go Israel’s way. That’s like saying that because the Los Angeles Dodgers do not win all their games, it can’t be true that they are one of the strongest teams in baseball.

Adding to this, Mead pooh-poohs the idea of lobbies in general, asserting that if a lobby is successful, it’s only because there already was strong popular support for the position it is advancing. Of course, any lobby seeks to build on pre-existing public sentiment, but the whole purpose of a lobby is to go beyond whatever policy such sentiment would naturally produce on its own. An instructive comparison is with the gun lobby. Many Americans really love their guns and probably would love them even if the National Rifle Association did not tell them they should. But the gun lobby, led by the NRA, needs to be a big part of any explanation for the repeated failure to enact even those gun control measures that polls consistently show most Americans favor.

When, in the midst of Mead’s historical narratives, one comes across a clear instance of domestic politics rather than sound foreign policy strategy leading to a decision to Israel’s liking, Mead does not confront such a data point directly. His technique instead is to say something like, “sure, that’s how the Vulcanists would interpret it, but it’s not that simple, and you have to understand the broader context.” He then embarks on a discussion of context that goes on at such length that by the time he finishes, most readers would have forgotten details about the original data point.

A prime example is President Harry Truman’s decision in 1948 to quickly recognize the self-declared State of Israel, notwithstanding the strife that already was afflicting Palestine. Truman himself characterized the political situation he faced around this time when he told a delegation of Middle Eastern representatives to the United States, “I’m sorry gentlemen, but I have to answer to hundreds of thousands who are anxious for the success of Zionism; I do not have hundreds of thousands of Arabs among my constituents.” The president’s decision came after a showdown meeting in May 1948 in which Truman’s political adviser Clark Clifford, using talking points he prepared in consultation with Zionist advocates, argued for recognition against the strong opposition of Truman’s national security advisers, led by Secretary of State George C. Marshall.

When Mead, after 90 pages about the post-war order that Truman was trying to build internationally as well as the domestic issues of the day, finally circles back to that May 1948 meeting, he tries to argue that Clifford was not advocating a “narrow political strategy” but instead a strategy that would enable Truman to regain support he had lost when he earlier had shown signs of considering a different policy for Palestine, and, with that support, to be able to “sustain exactly the foreign policy” that Marshall and his colleagues considered essential. Translation: Truman took a position that would give him domestic political support, which would help him win re-election, which would enable him to keep setting policy both foreign and domestic. In short, partisan politics was at work.

Besides, the idea that the direction of postwar U.S. foreign policy depended on Truman’s political support and re-election is not valid when one considers even more of the context than Mead does. The chief elements of U.S. foreign policy in the early Cold War years enjoyed bipartisan support that would be unheard of today, with Senator Arthur Vandenberg, the dominant Republican voice on foreign policy, working in close partnership with Truman on matters such as the Marshall Plan and the creation of NATO. If Thomas Dewey — whom the isolationist Taft wing of Republican Party criticized for his “me too” approach to foreign policy under Roosevelt and Truman — had defeated Truman in the 1948 presidential election, it is unlikely those elements would have changed appreciably.

With this and other episodes, Mead resists acknowledging that there is such a thing as the national interest, which is upheld by apolitical public servants such as Marshall — and which can be damaged by decisions driven by domestic politics. In an introductory chapter he disses the whole concept of a national interest, the same way he dissed the concept of a lobby. He tries to demean Marshall and the national security professionals at the time of the 1948 decision as being naïve about the importance of political support and mistaken about the outcome of fighting between Jews and Arabs in Palestine.

In fact, those officials were remarkably prescient about the major and especially long-term consequences of what happened in Palestine then and about the implications of the recognition decision for U.S. interests. The Near East Bureau at the State Department accurately predicted the severe refugee problem that resulted and the large-scale reliance of the Jewish state on U.S. assistance. Intelligence assessments at the time correctly anticipated the damage to U.S. interests in the Muslim world, as well as the future Israeli expansionism that has defined the Israeli-Palestinian conflict of today.

In a book of some 600 pages that is filled with digressions and detail — ranging from the choreography of Theodor Herzl’s meetings with Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1898 to the lighting system in the White House during Benjamin Harrison’s presidency — neither the author nor the publisher can cite lack of space as an excuse for its omissions. And in a book dedicated to knocking down any idea of an Israel lobby influencing U.S. policy, the omissions are enormous. Besides ignoring the scholarship on this subject, there is almost no attention to the ample direct evidence of the lobby at work.

Take as one example the role of the late casino magnate and megadonor Sheldon Adelson, who receives only a single half-sentence mention in Mead’s book. Adelson and his wife were the biggest individual donors to Trump’s campaigns in both 2016 and 2020. Although evangelical Christians were still Trump’s main base of support and reason for his policies toward Israel, it would be hard to overstate Adelson’s role in influencing policy, at least as far as the Republican side of the political spectrum is concerned. That role became so large that a rite of passage for Republican presidential aspirants was the “Sheldon primary” — a trip to Las Vegas to seek Adelson’s favor. And Adelson’s overwhelming policy concern was anything involving Israel, which he made clear was the nation he loved the most.

Nor does Mead give any attention to the role of other “pro-Israel” money in American politics. Nor to the proud boasts by core members of the lobby itself about its influence with American politicians. Nor to the direct testimony of members of Congress — which I have heard in off-the-record conversations in the privacy of their offices, and admittedly would be difficult for any book to document — about the power of the lobby.

Regardless of the specific mix of factors — popular sentiment, the work of lobbies, and other influences — that underlay what the U.S. relationship with Israel has become, the important policy question is how that relationship hurts or helps U.S. interests. Here Mead does identify one of his targets, which he labels “realist restrainers.” And to his credit, for the most part he fairly and accurately summarizes what that school of thought represents, with a reference to Andrew Bacevich, president of the pro-restraint Quincy Institute. Realist restrainers see overextension and overcommitment by the United States as causing more problems in the Middle East than it solves, viewing the relationship with Israel in its present form as one aspect of the overcommitment that could usefully be pared back.

But after stating the restrainers’ position, Mead does not directly engage it (other than with an attempt at a theoretical argument that clumsily confuses the descriptive and prescriptive aspects of realism) or offer reasons why the reader should not be persuaded by a policy recommendation that obviously is not one that Mead prefers. Instead, he indulges once again in his fixation with bashing the concept of an Israel lobby and attempting to associate any mention of the lobby with prejudice against Jews. He acknowledges that the realist restrainers’ position “does not necessarily lead to Vulcanism” but insists that many restrainers have found “compelling reasons” to subscribe to the “Israel lobby thesis,” which has “electrified antisemites around the world.”

Mead does not want American Jews to be blamed for whatever Israel does, and he certainly is right that such an attribution of blame would be unwarranted. But he does not seem to have any compunction about blaming Americans who talk about the Israel lobby for whatever antisemitism exists. And this attribution of blame is just as unwarranted as the other one.

“The Arc of a Covenant” can be appreciated for well-written history on the topics that Mead has chosen to address. But don’t take it as a comprehensive analysis of the causes of the U.S.-Israel relationship, which the book definitely isn’t. And be careful not to stumble on the “Vulcanism” parts, which come across as crude polemics unworthy of the historian who wrote the rest of the book.