Instead of redeploying American military forces to Somalia in support of the Somali National Army’s war against al-Shabab, the Biden administration should rely on diplomacy to help resolve the conflict.

This may not be a message the administration wishes to hear, but locally-led diplomacy that includes al-Shabab, leaders of rival clans and sub-clans, and Gulf Arab countries, offers the best hope for achieving a measure of stability in a country that has been fractured by more than 30 years of warfare, lawlessness, and state failure. Stability in Somalia requires that all political actors convene, including al-Shabab, in an effort to negotiate a new set of rules, behaviors, and norms for politics and the use of violence. Due to its narrow focus on military outcomes, American policy makers have failed to understand the extent to which local identity and clan politics contribute to violence and instability in Somalia.

To facilitate this, the Biden administration will need to roll back restrictions on engaging with al-Shabab, which has been listed as a Foreign Terrorist Organization since 2008. And Biden’s State and Defense Departments will have to work with Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Qatar to push local political leaders to talk to one another and to al-Shabab.

Since 2007, Washington has focused on managing the conflict in Somalia by “mowing the grass,” a strategy adopted from Israel that is focused on debilitating al-Shabab’s military capacity with no ambition or prospect of achieving an ultimate resolution of the conflict. But this approach has never worked; it has only made Somalia more violent and unstable.

In the 20 years that followed the October 1993 Battle for Mogadishu, the United States kept out of direct conflict in Somalia. Instead, it supported various Mogadishu-based warlords and Ethiopian and African Union conflict stabilization efforts, primarily through AMISOM, the African Union Mission in Somalia. But by 2007, Washington was deploying small numbers of special forces to Somalia in support of AMISOM. And in 2011, U.S. warplanes and drones began conducting airstrikes against suspected al-Shabab forces and leaders.

In March 2017, President Trump expanded ground operations and loosened the rules of engagement for U.S. forces operating in Somalia — rules that were designed to protect civilians. As a result, the number of American airstrikes tripled over the next three years during which the U.S. military conducted 151 airstrikes and seven ground operations (compared to 58 airstrikes from 2015 to 2017). It also trained and supported an elite Somali military unit, the Danab (“Lightning”) Brigade.

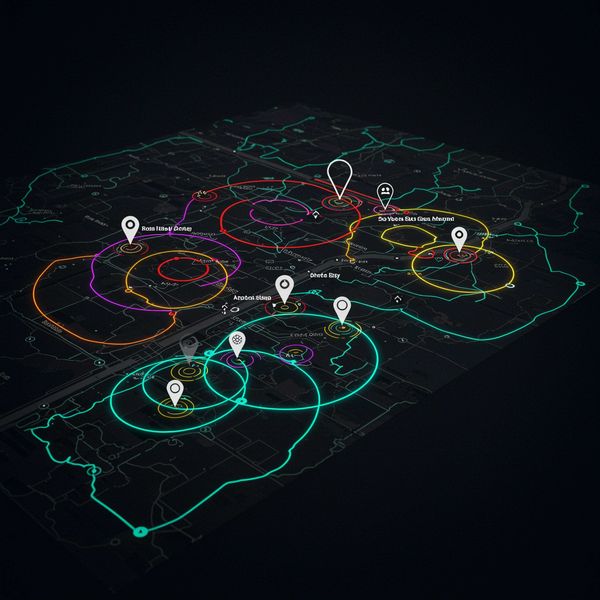

But American military investments failed to produce results. As the U.S. military footprint in Somalia grew, so did violence. Data from ACLED (the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project) demonstrate that since 2007, violence throughout the country increased year after year. The number of battles and incidents of violence nearly doubled between January 2017 and December 2020, the period covering the most intense U.S. military activity in Somalia.

And, despite U.S. training and support, the Danab brigade has generally been unable to hold the towns it has cleared from al-Shabab forces. Worse, the unit has been credibly accused of killing civilians and making arbitrary arrests. The United States formally reviewed its support for the unit after it was found to have taken part in a battle against a former regional ally. The fight was linked to a festering dispute over the ally’s political representation in local, state, and national government.

Before leaving office in January 2021, Trump withdrew U.S. forces from Somalia and instead had them “commute” to Somalia from bases in Kenya. In early 2022, however, al-Shabab ramped up attacks throughout the country with the goal of undermining the presidential election. The increased violence, AFRICOM’s suspicion that al-Shabab had the capacity to attack Americans outside of Somalia, and the inefficiency and cost of ferrying American troops in and out of the country persuaded the Biden administration to redeploy about 450 American special forces troops to Somalia in June this year as part of the latest phase of mowing the grass.

Al-Shabab was born in 2007. It grew out of the collapse of the Islamic Courts Union (ICU), a group that emerged from the Somali civil war in control of large swaths of southern Somalia between 2004 and 2006. Al-Shabab’s members included the most hardline ICU fighters, as well as recruits from different Somali clans and regions and some foreign al-Qaida-linked fighters. Its brutality and al-Qaida links led the Bush administration to list it as a Foreign Terrorist Organization as part of the Global War on Terror in 2008. The group swore allegiance to al-Qaida in 2012.

The organization’s diverse membership is not a new phenomenon. For decades, national rebel groups in Somalia have formed through inclusive elite bargains, collaboration, and coalition-building between militant groups, clans, the business sector, and elements of the national government. The groups that ejected long-time U.S.-backed dictator Mohamed Said Barre from power in 1990, as well as the ICU a generation later, were amalgams of various forces, including business interests, religious militants, and clan and sub-clan leaders. Al-Shabab replicated this structure with deadly effectiveness.

In interviews I conducted with security experts in Mogadishu in 2017, participants told me that many militants in Somalia were nationalists above all, determined to fight foreign intervention in their country. This buttresses a growing body of research indicating that al-Shabab shifted its focus away from international terrorism towards local issues. Al-Shabab’s early rejection of Somali clan identities, national borders, and Sufi traditions in favor of transnational militant Islamist ideology created tension with Somalia’s large Sufi community. This undermined support for the organization. So the group turned away from foreign fighters in 2013. Even with its internal focus, the group has conducted several large attacks outside of Somalia in last decade, most recently in Ethiopia.

Despite its record of brutality, al-Shabab, locally, has proven adept at providing food aid during drought, administering justice and resolving local disputes, criticizing Mogadishu government’s governance record, and providing public safety.

Interviews with mid-ranking al-Shabab leaders reveal that their members are open to dialogue with the Mogadishu government. Its conditions for negotiations include the withdrawal of all foreign forces from Somalia, amnesty for group members, adopting Sharia law, and creating a new inclusive government consisting of all Somali political actors.

While several of al-Shabab’s conditions for peace negotiations are nonstarters, members’ openness to dialogue on forming a new and inclusive government is a valuable launching point. An effective method for achieving stability in fragile and violence-affected countries is to facilitate maximally inclusive elite bargains and political deals. Stabilization and peacebuilding efforts need to include as wide an array of local political leaders and formal and informal power brokers as possible.

For peace talks to begin, Washington will have to reconsider its role in the conflict. At a minimum, it will need to remove al-Shabab from its terrorism list and pull back its military forces. The African Union Transition Mission in Somalia and other foreign forces will have to follow suit. Washington will likely have to deemphasize its role in peacebuilding as well. According to al-Shabab members, Qatar and Saudi Arabia could serve as peace talk facilitators. The United Arab Emirates will have to be included in peace talks as well because of its local influence. Kenya and Ethiopia, whose militaries have fought in Somalia and been subjected to al-Shabab violence, will need to be included because Somali security directly impacts them. Regardless, peacebuilding will be a multilateral affair, modelled potentially on American-Taliban talks.

Mowing the grass in Somalia has made the country more violent and unstable. Instead of trying to contain or eliminate al-Shabab with military might, Washington should rely on inclusive diplomacy to resolve the conflict. This may be an unappealing option for Washington because of al-Shabab’s history of violence. But this approach could get the Biden administration what it says it wants — a less violent Somalia and a more peaceful East African region.