For some years now, observers of military and security affairs have levied rightful criticism at America’s growing string of military failures abroad. We don’t win wars anymore. We don’t prevent wars. We can’t end wars.

At the heart of these repeated operational failures, many think, are deeply embedded intellectual failings that reflect inexcusably underdeveloped strategic understanding on the part of America’s current generation of generals and admirals.

At least since the 2018 National Defense Strategy (NDS) document appeared, such criticism has led to accusations that the U.S. military’s Professional Military Education (PME) system, especially the senior, “war college” level of that system, is to blame. The 2018 NDS, then-Secretary of Defense James Mattis’s homage to his own thinking, made this unsubstantiated assertion:

PME has stagnated, focused more on the accomplishment of mandatory credit at the expense of lethality and ingenuity. We will emphasize intellectual leadership and military professionalism in the art and science of warfighting, deepening our knowledge of history while embracing new technology and techniques to counter competitors. PME will emphasize independence of action in warfighting concepts. . . .

Regrettably, such uninformed accusations fail to recognize that the real culprit in producing a generation of intellectually challenged senior military leaders isn’t the military’s professional schooling system. It is military culture itself, the selfsame culture in which and by which Mattis — and others like him — have been indoctrinated. More about that momentarily.

It is especially ironic that a tactically minded soldier like Mattis would levy such ill-founded claims about "strategic thinking" against PME. His familiarity with PME was limited to being a student in the junior Marine Amphibious Warfare School, the mid-level Marine Command and Staff College, and the senior National War College. He was never an instructor or administrator at any military school. It is also a reflection of his tactical military hard-wiring that he would associate intellect and education with “lethality” and “warfighting,” two chest-thumping rhetorical labels totally antithetical to the development of the mind.

Mattis’s anti-PME bias led, at his direction, to the 2019 creation of the Secretary of Defense Strategic Thinkers Program (STP), a master’s degree-granting enterprise conducted under contract to DoD by the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies. The thinking behind this, obviously, was that rather than seeking to enhance and elevate the quality of the existing educational programs of the military’s schools by reorganizing, reformulating parochial guidance, or improving instructor, student, and managerial quality, it is preferable to just farm things out to a name-brand civilian institution and take credit for establishing a gimmicky new program ostensibly best positioned to produce bona fide “strategic thinkers.”

The most recent treatment of the subject, a commentary by retired Air Force Brigadier General Paula Thornhill, an associate professor in the Hopkins program (as well as a former dean at the National War College), keeps alive the only thinly veiled criticism of PME. The supposed superiority of the STP, she suggests, lies in its use of small, tutorial-style seminars, wargames, staff rides, and civilian-based public policy instruction — as if these aren’t methods employed by PME institutions already.

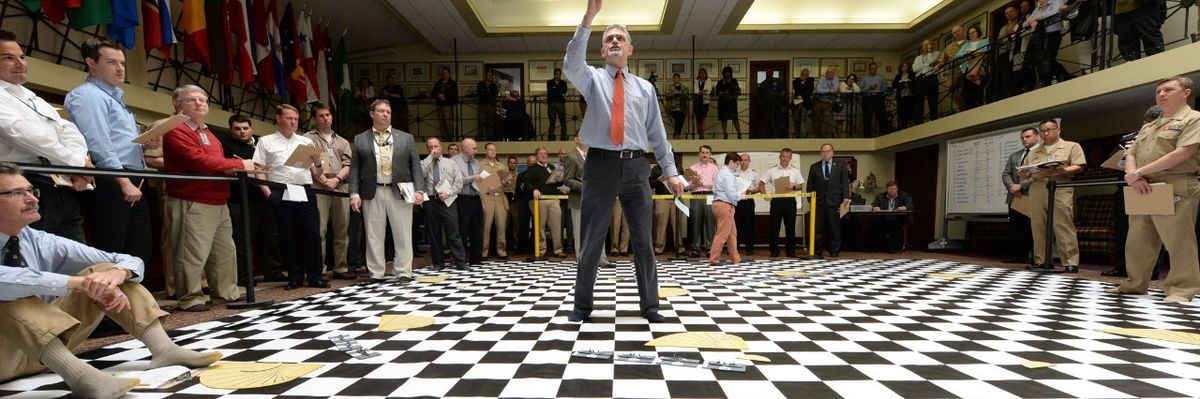

Her abbreviated description of the STP prompts a number of questions for those who know anything about strategic education: Do these tutorial-style seminars rely on didactic lectures and passive learning, or on Socratic dialogue that some say is the singularly necessary precondition for developing strategic thinking? Is there more sophisticated, more realistic wargaming expertise in a civilian institution that is somehow superior to the wargames and exercises employed at PME institutions? And do such wargames actually test the intellectual mettle of participants more than, say, serious Socratic questioning and dialogue? Can staff rides – over battlefields like Gettysburg, the Somme, Normandy, Inchon, or Khe Sanh, for example – actually develop strategic deliberation and insight, or are they little more than militarily-oriented terrain walks?

The STP is, by design, an elitist program: you apply, you compete, and you’re either selected or not, presumably on the basis of merit. PME schools, on the other hand, are populist institutions whose students are involuntarily selected by their parent services and organizations based on past performance and future potential in operational assignments, not on academic achievement or intellectual acumen. It is a normal distribution of generally high-performing operational types who lay no claim to academic or intellectual superiority.

So how, if at all, can we compare these two avenues for producing strategic thinkers?

Faculty. There is literally nothing to distinguish STP and PME faculties from one another. As with any educational or training undertaking, faculty expertise and quality is a crapshoot, a random walk through teacherdom. In all cases, regardless of locale, students may end up with either exceptional or mediocre, narrow- or broad-gauged, visionary or myopic faculty, depending on how the pedagogical stars align.

Curricula. Curricula for any programs that claim to produce strategic thinkers don’t lend themselves to ready comparison, not least because there is no template that prescribes what constitutes or best contributes to strategic thinking.

The foundational principle that underlies all leadership development programs is that leadership isn’t strictly innate; it can be learned and acquired. And, because strategic leadership is fundamentally an intellectual rather than a behavioral enterprise, strategic thinking therefore can also be developed.

What is too rarely recognized, much less articulated, is that strategic thinking is qualitatively distinct from garden-variety thinking, regardless of domain or context, be it political, bureaucratic, ideological, legalistic, or scientific. It transcends military thinking, which by nature is narrowly tactical and operational, and the conduct of war (arguably the result of non-strategic thinking). Its focus is on the future, on the holistic big picture, on the nth-order consequences of action or inaction, on underlying causes rather than the symptoms of the moment.

What remains unanswered if not unanswerable is what disciplines and what subjects are essential or even best suited to the development of strategic thinking: military affairs? history? political science? international relations? philosophy? geography? law? economics? demographics? What about art, music, literature, or religion? Civil-military relations? Ethics? Political institutions and processes? Organizational theory? Forecasting? Regional and cultural studies? There is no right answer.

Students. Ultimately, it is the quality of students — the experience, expertise, values, attitudes, and intellectual wherewithal they bring to these programs — that matters most. Students are both the random raw material that feeds into the educational enterprise and the marginally less random finished product that comes out at the other end.

Thus, in the final analysis, it is the culture that surrounds and shapes these individuals — before, during, and after their educational interlude — that ought to be of central concern in judging their present and future performance as strategic thinkers.

The culture those in uniform inhabit is with them forever, from the beginning to the end of their professional careers. Their educational involvement is but a brief interlude that may be influential in some modest measure at a particular point in time, but it certainly isn’t – and shouldn’t be thought of as – determinative.

By the time military officers — lieutenant colonels and colonels, or the Navy equivalent — are eligible for senior PME, they have at least 15 years of professional experience in operational assignments under their belt. Following their abbreviated academic experience, it will be another ten years before a small percentage of them reach senior rank. All that time, their culture is with them and within them. They are fully socialized in a hierarchical, authoritarian institution that preaches, extols the virtues of, and lays singular claim to the practice of leadership, but in reality nurtures and rewards dutiful followership.

It is a culture that sanctifies command and, accordingly, demands unquestioning obedience to rank- and position-based authority, discourages dissent, forbids disobedience to orders and even expectations, expressed or implied, and underplays the importance of consensus building. Action (getting things done) always takes precedence over reflection (thinking things through); and implementation (carrying out the direction of others) trumps origination (generating new ideas), meaning that critical and creative thinking are undervalued and frequently go unrewarded.

Reactive crisis management, rather than proactive crisis prevention, is the operative norm. Secrecy (withholding privileged information) invariably overrides transparency (exposing or sharing information). Training (applied, job-related skill development) regularly takes priority over education (general intellectual development). Writing, as both reflection of and stimulus to sound thinking, almost always takes the form of formulaic, strictly formatted decision memos and point papers, rather than expository expression.

And, finally, PME institutions themselves, which are both educational institutions and military organizations, consistently opt for the latter over the former as their reason for being and the source of their legitimacy. All of these facets of military culture have a pronounced, inhibiting effect on the quality of thinking of those in uniform.

Henceforth, if we are to confront our strategic failings abroad by acknowledging the intellectual limitations of today’s generals and admirals, it is imperative that we accurately diagnose the source of those limitations, avoid uninformed and shallow accusations, and place blame where it properly belongs: on military culture itself.