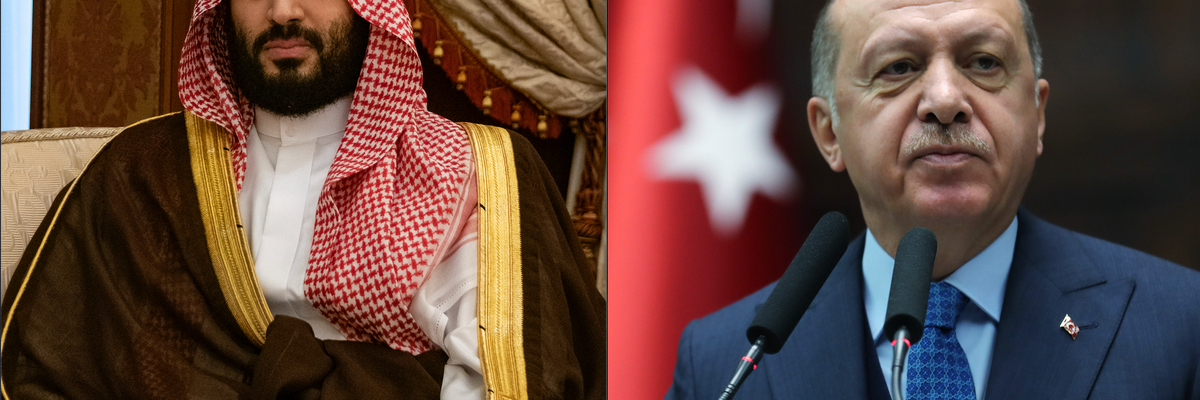

Reports that Saudi Arabian Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman may be planning to visit Turkey as part of an international trip in June, one of his first outside the Gulf region since the 2018 killing of Jamal Khashoggi, have added to the sense of rapprochement in bilateral relations between Riyadh and Ankara. A decade of increasingly confrontational policies that pitted Saudi and Turkish leaders against each other across a range of issues appears to have given way to a period of greater pragmatism in inter-regional relations. In part, this is consistent with, and part of, a broader regionwide de-escalation of tension that has been underway since 2020. For officials in Riyadh—as well as in Ankara and elsewhere in the region—domestic issues are being accorded greater weight than foreign policy ones in the era of COVID-19 and as Vision 2030 begins to come into focus for the kingdom’s millennial leadership.

Removing the Impact of the Irksome Assassination

After initially falling behind the improvement in relations between Turkey and the United Arab Emirates, developments in April 2022 indicated that Saudi and Turkish leaders have decided, at least for the time being, to move beyond the contentious issues that had defined the previous era in bilateral ties. From the Saudi side, the key to unlocking the problems of the past was the April 7 decision by a panel of judges in Istanbul to approve a request by Saudi authorities to transfer the trial (in absentia) of 26 Saudi suspects in Khashoggi’s murder to the Kingdom. Media reports at the time had suggested that officials in Riyadh had made the closing of the Khashoggi file a condition of any improvement in relations with Turkey. A separate article on US-Saudi relations in the Wall Street Journal which claimed that Mohammed bin Salman had lost his temper after National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan raised Khashoggi during a meeting in September 2021 indicated that journalist’s affair remained an extremely raw issue for the crown prince.

Tensions between Saudi Arabia and Turkey therefore were more personal than those between the UAE (and especially Abu Dhabi) and Turkey, which were more ideological in nature, and had more to do with the two countries’ leadership’s different perspectives on political Islam and the Muslim Brotherhood. Some in Ankara accused the UAE of involvement in the failed coup attempt against President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in July 2016, and the ideological dispute between Ankara and Abu Dhabi then took a military dimension in 2019-20 when the two supported rival groups battling each other for control of Libya. Turkey’s intervention in support of the internationally recognized government in Tripoli was seen as a critical factor in thwarting the UAE, Egypt, and Russia-backed warlord Khalifa Haftar’s attempt to seize the capital.

Although Saudi authorities designated the Muslim Brotherhood a terrorist organization in March 2014, the Saudi move was more concerned with putting pressure on Qatar in that year’s iteration of the Gulf states’ diplomatic rift, as it came the day after Saudi Arabia (together with the UAE and Bahrain) had withdrawn their ambassadors from Doha. The UAE followed suit eight months later and Abu Dhabi actively lobbied foreign governments, including David Cameron’s in the United Kingdom, to adopt harder-line positions on the Brotherhood. Evidence from Yemen—where Saudi authorities were willing to work with Islamist and Muslim Brotherhood-linked groups on the ground—suggests that, on this issue, Riyadh had a more flexible, even pragmatic, approach than the UAE’s rigid position in the 2010s.

While Saudi Arabia joined with the UAE in blockading Qatar in June 2017, and in demanding the ending of military cooperation between Turkey and Qatar as one of thirteen conditions for resolving the dispute, it is generally accepted that the break with Doha originated more in Abu Dhabi than in Riyadh. It was the horrific circumstances of the murder of Jamal Khashoggi in the Saudi Consulate in Istanbul, in October 2018, and the stream of allegations from the subsequent Turkish investigation, that created the deep friction in the relationship between Riyadh and Ankara, in part as neither President Erdoğan nor Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, headstrong characters both, seemed willing to act to heal the rift. A 2018 visit to Turkey by Prince Khalid al-Faisal Al Saud, the respected Governor of Mecca, at King Salman’s behest, was unable to repair the fracture in ties that had opened as a result of the Khashoggi killing.

Persistent reports of an unofficial and informal Saudi boycott of Turkish products, given credence by a plunge in the value and quantity of Turkish exports to the Kingdom between 2019 and 2021, drew attention to the breakdown in relations in the post-Khashoggi standoff. The animosity extended to Saudi media outlets and commentators urging their compatriots not to vacation in Turkey in an atmosphere of hyper-partisan and increasingly nationalistic public support for Mohammed bin Salman. This occurred against the backdrop of an unprecedented accumulation of political power and decision-making authority by the crown prince. As a result, the association of Mohammed bin Salman with the Khashoggi fallout, implied by President Erdoğan when he blamed ‘the highest levels’ of the Saudi government but pointedly stated that this did not implicate King Salman, had an inordinate impact on the conduct of state policy so long as the issue was ‘live’ and unresolved.

What, then, has changed to improve bilateral ties between Saudi Arabia and Turkey to the extent that Mohammed bin Salman and Erdoğan publicly embraced during the latter’s April 28 visit to Jeddah, his first in more than a decade to the Kingdom? A separate essay by colleague Mustafa Gurbuz examines the Turkish side of the equation, but the remainder of this explores what motivated the Saudi leadership to add Turkey to the list of regional relationships that have improved in the past two years. To be sure, the shift in the Turkish stance over Khashoggi, to the outrage of human rights advocates and the friends and family of the murdered columnist, was pivotal, but other contextual factors are important as well.

Impactful Changes in Saudi Policies

Several issues underlie the broader spirit of reconciliation that has characterized regional dynamics since 2020. One is that COVID-19 has hit each country in the region (and the world) and focused policymakers’ attention far more onto the domestic arena, both in charting public health responses to the pandemic and in navigating the uncertain transition into the post-pandemic landscape. Another is that the defeat of Donald Trump in the 2020 US presidential election signaled an end to the period of unconventional and raw power politics that had dominated the previous four years, at least until 2024. A third was that, in Riyadh as in Abu Dhabi, signs of vulnerability had punctured the muscular assertiveness that had marked Saudi and Emirati regional policymaking between 2015 and 2018.

For Abu Dhabi, it was the limits of its ability to transform the projection of military power into political gain in Libya and, to a lesser extent, Yemen, but for the Saudi leadership it was the September 2019 missile and drone attacks on oil facilities in Abqaiq and al-Khurais, as well as the lack of an American response, that underscored the need to change course and de-escalate tensions in the region. Within weeks of the Abqaiq attack, Saudi officials reached out to Iranian counterparts via intermediaries in Iraq, and Emirati officials engaged directly with Iranian officials in July 2020 after a spate of incidents involving shipping off the UAE coastline. For all the close coordination in Saudi-Emirati regional policies, it was instructive that each pursued their own separate pathway of dialogue (and de-escalation) with Iran, just as they have also done with Turkey. This is an indicator that individual leaders are prioritizing their own pursuit of national interests over and above any conception of the informal regional blocs that were seen by many to pit Saudi Arabia and the UAE against Turkey and Qatar in the late 2010s.

Mohammed bin Salman has followed two distinct yet not unrelated approaches to regional and domestic policy since 2020 and both may become clear as relations with Turkey evolve. To external audiences, the crown prince has presented himself as a figure of regional importance and sought to craft an image of a statesman who is far removed from the reputation for acting recklessly that he gained after 2015. This was evident in the way the crown prince was front and center at the ‘reconciliation’ summit at Al-Ula, Saudi Arabia in January 2021 which ended the three-and-a-half-year rift with Qatar, as well as in Mohammed bin Salman’s tour of other Gulf capitals in December 2021, ahead of the next Gulf Cooperation Council summit. Since then, events have further strengthened the Saudi hand, with surging oil prices and revenues resulting from the dislocation of the Russia-Ukraine war adding to the sense in Riyadh that the kingdom has leverage over regional and international partners, such as the Biden Administration.

At the same time, there has been an emphasis on focusing internally on Saudi domestic policy as the worst of the pandemic passes and as Mohammed bin Salman moves inexorably closer to succeeding his father. King Salman looked extremely frail as he was discharged from the King Faisal Special Hospital in Jeddah on May 15 after an eight-day stay for a colonoscopy, and it was notable that the crown prince waited until after his discharge before he flew to Abu Dhabi to offer condolences to Mohammed bin Zayed on the death of his brother, President Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan. Separately, in a post-pandemic environment and as the visionary year of 2030 draws ever closer, Mohammed bin Salman will face greater urgency in delivering tangible economic progress that meets the expectations that Vision 2030 will transform Saudi Arabia and the lives and prospects of Saudi citizens.

If one aspect of pandemic-era policy has been growing competition with the UAE in regional markets, another is the salience of revitalizing those areas of the Saudi economy, such as travel, tourism, hospitality, and entertainment, that have been hit hard by COVID-19, yet which have been prioritized for development by Mohammed bin Salman and his economic and policy advisors. In this context, it makes little sense for one of the region’s largest markets to be shut out for political reasons, just as access to Turkey could, in the other direction, be a significant boost for business for Saudi conglomerates. And yet, it is the defense sector, and defense industry cooperation, which looks set to be an early priority for Saudi officials as relations with Turkey revive.

Two Saudi entities already have an agreement with Vestel Savunma to co-produce the Karayel-SU unmanned combat aerial vehicle in the Kingdom, with reports indicating that the drones have been deployed operationally by the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen. The next step in any defense-led relationship may be Saudi acquisition of Bayraktar drones—which have proven themselves on multiple battlefields, including Libya’s, in recent years—as well as cooperation agreements involving Saudi Arabian Military Industries (SAMI) and Turkey’s advanced defense sector. Any participation by Turkish companies in SAMI’s plan to localize 50 percent of Saudi defense spending on domestic supply chains by 2030 could provide significant benefit to both countries and be a springboard for additional and wider partnerships.

Improving ties between Saudi Arabia and Turkey are therefore likely to focus on securing bilateral interests for each party and less likely to create a new power bloc or regional realignment, at least for the next several years as the broader atmosphere of regionwide reconciliation persists. Warmer Saudi ties with Qatar since 2021 do not appear to have been related to the signs of competitive rivalry with the UAE in the same period, and there is little reason to believe that a rapprochement between Riyadh and Ankara would affect Saudi or Turkish relations with other regional states. More direct impacts may instead be seen in changing media coverage and the ending of Turkey’s 2010s-era reputation as a haven for political dissidents from Middle Eastern countries, including the UAE, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia.

This article was republished with permission from Arab Center Washington DC