With all the attention devoted to the April 24 French presidential election, it was easy to overlook the parliamentary voting in another EU and NATO country — Slovenia.

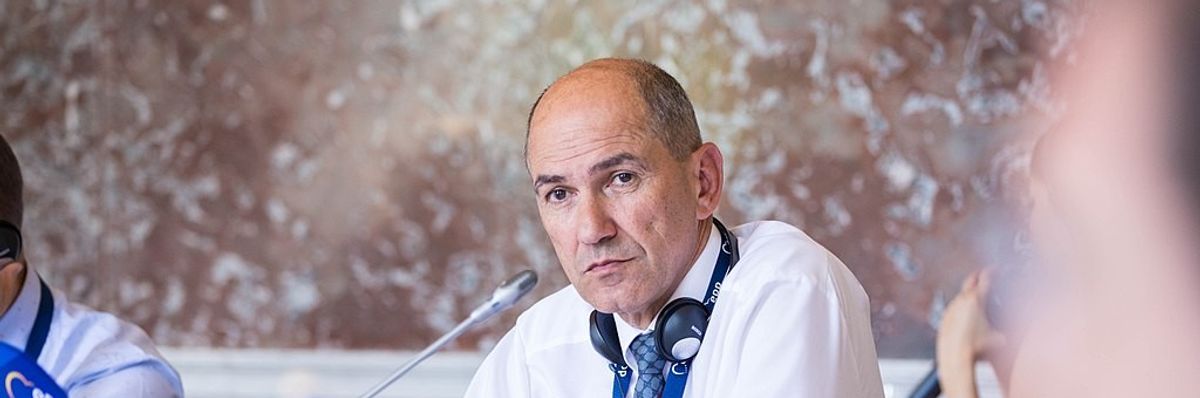

The two-million-strong nation delivered a resounding rebuke to conservative incumbent Janez Jansa and handed victory to the environmentally-minded Freedom Movement. The outcome is likely to be a left-leaning coalition led by Movement leader Robert Golob with the social-democrats and a smaller party to their left as junior partners.

Slovenia may not often make the news in the United States, but the outcome of these elections is significant for the future of the U.S. European policy.

It has been the consistent U.S. policy since the end of the WWII to support European integration as a path to sustainable peace and prosperity on the continent. All post-war U.S. presidents supported it, with the exception of Donald Trump, whose contempt for the EU is well known.

President Biden has reverted to the traditional U.S. line on Europe. In that view, a peaceful Europe serves the U.S. interest in that Washington will not need to fight wars to save the Old World from itself and instead can use a united Europe as a force multiplier for its own great power competition with Russia and China.

That largely still holds true, with overdue and necessary adjustments, notably the wealthier EU nations assuming greater responsibility for their own defense. But that shouldn’t be a source of tension with Washington as Europe’s most influential politician — French President Emmanuel Macron, who was just re-elected for another five years — is himself a strong proponent of the EU’s “strategic autonomy,” a code word for greater self-reliance in defense matters. A U.S.-allied united Europe at peace with itself and ready to assume more responsibilities in the world would indeed be a strong asset for Washington, notably in the ongoing efforts to resist Russian aggression in Ukraine, and, in the near future, to check Chinese power.

However, Europe’s present and future stability will remain an elusive prospect so long as the Western Balkans are not fully integrated into it. The region was the site of much bloodshed in early 1990s, and the United States was deeply involved, including militarily, in efforts to end it. The region’s integration in the EU should be seen as a way to stabilize it and anchor it firmly within the West. Washington has consistently supported that effort.

In recent years, however, the region has reverted to some of its old bad habits — historical revisionism, ethnic nationalism, the failure to protect minorities, corruption, and attacks on the rule of law by aspiring strongmen. It is partly a result of the EU’s own faltering commitment to enlargement — the last new member, Croatia, joined in 2013, and there is no realistic prospect of any new countries joining any time soon.

Worse, that erosion didn’t leave even the existing EU members unscathed. Outgoing Slovenian prime minister Jansa has proved deeply divisive. Like his close ally, Viktor Orban, the long-serving prime minister of Hungary, he sought to subvert the country’s institutions, such as the judiciary, and cow the independent media into submission. According to Freedom House, a democracy watchdog, Slovenia experienced a sharp decline in its democratic governance over the past few years. Were Slovenia to remain on the same trajectory, sooner or later it would have come into an open conflict with Brussels, as Poland and Hungary already have. At a time when European unity is a prized asset in dealing with Russia, internal divisions in the EU would likely prove be detrimental to the United States.

Jansa also played a problematic role in the broader Balkans. Last summer, a mysterious non-paper, attributed to him, created ripples in Brussels. The document, whose authorship Jansa neither confirmed nor denied, proposed an ambitious redrawing of the borders in the Western Balkans, including carving out ethnic statelets out of Bosnia and Herzegovina, itself a fragile product of the bloody break-up of Yugoslavia. It also proposed redrawing the borders of Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Albania, stoking fears of fresh fighting and ethnic cleansing. The separatists in Bosnia, such as the notorious Bosnian Serbian leader Milorad Dodic, would be among the chief beneficiaries of the plan. It was no coincidence when Dodic openly endorsed Jansa for re-election.

A reignited ethnic conflict in the Balkans would broaden the spectrum of Russian interference and create a massive distraction for both the EU and NATO. Instead of investing in its fledgling efforts to upgrade its defense capabilities, the EU would be tied down to a conflict in its own neighborhood. As recent history has shown, this would also create pressures for Washington to intervene — pressures it would find exceedingly difficult to resist.

Jansa also backed a number of hawkish policies at odds with the EU mainstream and U.S. preferences. In July 2021, at a time when the Biden administration was seeking to revive the nuclear agreement with Iran, known as the JCPOA, he addressed an online gathering of the Mojaheddeen-e Khalk, or MEK, an exiled anti-democratic cult-like Iranian opposition group. In his address, he essentially called for regime change in Iran. While speakers at MEK events, often retired Western politicians and officials well paid for their appearance, routinely issue such calls, what was highly unusual was the fact that Jansa did so in his capacity as the prime minister of the country that held the rotating EU presidency at the time.

That outburst provoked a mini-crisis in EU-Iran relations as Iran’s then-foreign minister Javad Zarif demanded clarifications on whether the EU was embracing regime change as its official policy and the MEK as its interlocutor. The EU high representative for foreign policy Josep Borrell had to reassure the Iranians that, due to the bloc’s complex institutional arrangements, Jansa could not speak for the EU whose policy towards Tehran remained unchanged. The new Slovenian government is expected to return to the EU’s default position on Iran, which is to seek the JCPOA’s renewal and explore additional avenues for engaging Iran. At least as far as the JCPOA is concerned, this would be much more aligned with the positions of the current U.S. administration.

On Russia, Jansa was one of the first European leaders to visit Ukraine in a show of solidarity and even advocated early on for the implementation of no-fly zones over Ukraine despite the risk that such a move is opposed by the Biden administration on the grounds that it would transform NATO into a belligerent in the Ukraine-Russian war. The new government in Ljubljana will stick to the mainstream EU and U.S. position on Russia — support Ukraine in all possible ways, enforce sanctions, but don’t drag NATO and the United States into a direct confrontation.

All in all, the outcome of the elections in Slovenia last week has aligned a key Balkan country much more closely to long-term U.S. interests in Europe at a key moment.

This article reflects the personal views of the author and not necessarily the opinions of the S&D Group or the European Parliament.