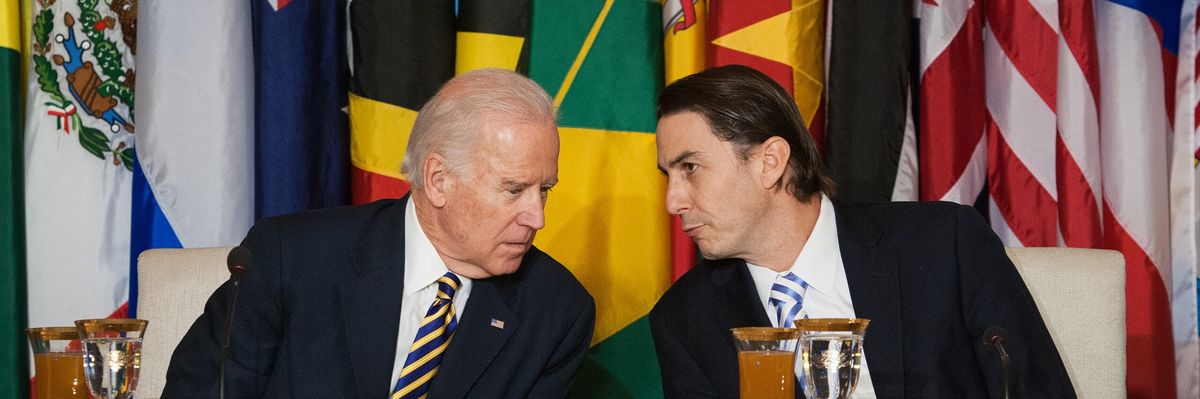

When President Biden appointed his personal friend and former Obama administration energy coordinator Amos Hochstein as his own energy envoy last summer, it seemed that the decades-old deadlock between Lebanon and Israel over their sea boundary, and potentially tens of billions of dollars in energy resources, might finally be resolved.

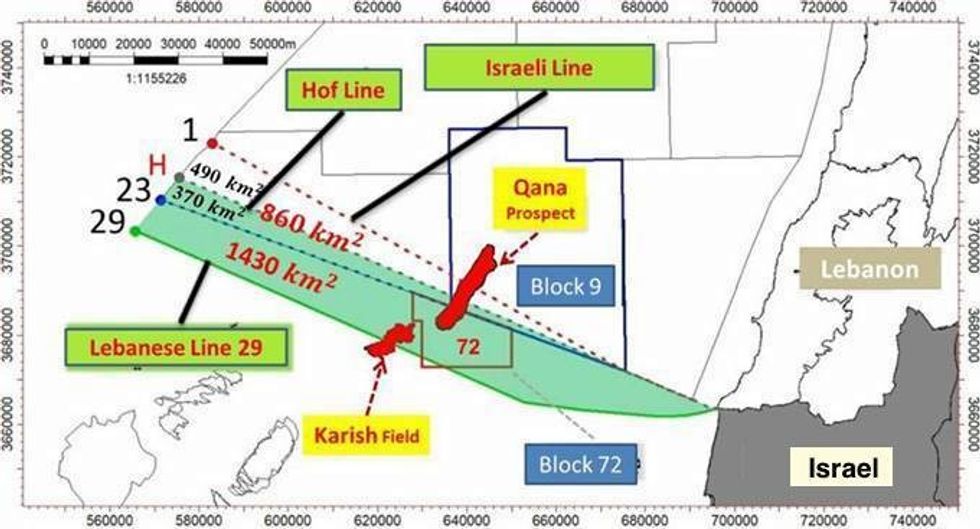

Hochstein was assumed to be trusted by the Israelis (he was born in Israel and served in the IDF in the early 1990s). He was perceived positively by some of the main Lebanese actors as a foe of a former U.S. envoy, Ambassador Frederic Hof, who had tabled a deal ten years before known as the “Hof Line” boundary that was widely seen in Lebanon as exceptionally unfair. And he came with a deep background in the complexities of the energy sector.

Perhaps most importantly, however, the Biden administration seemed hungry to claim a success in the Arab-Israeli conflict. Although a mutually agreed-upon sea boundary between Lebanon and Israel would fall far short of any Abraham Accord-type arrangement, such a deal would represent a UN-recognized boundary between a democratically elected Arab government and Israel. Given the extensive power of the armed Lebanese political party Hezbollah, which Israel considers its most formidable non-state enemy, the removal of a large offshore area from the regular military exchanges between the two sides onshore would also help to structurally diminish the prospects of another devastating war in the Middle East, something the Biden administration very much wants to avoid.

Unfortunately, eight months on, according to several senior Lebanese officials directly involved in the negotiations, the deal that Hochstein unveiled a few weeks ago in Beirut, one which apparently has Israel’s blessing, falls far short of Lebanon’s minimum acceptable position. As a result, the talks are in imminent danger of collapsing, perhaps in the coming weeks. Asked about this prospect, the State Department and U.S. Embassy in Beirut both declined to comment.

Hochstein, it seems, badly misunderstood the Lebanese side. First, in proposing that Israel and Lebanon share a potentially rich hydrocarbon field between them (known as the Qana Prospect after a town in South Lebanon), he has ensured that any deal is dead on arrival. No Lebanese political actor can muster the votes to essentially go into business with a state that is officially an enemy and regularly in military conflict with the most powerful political and military actor in the country, Hezbollah. Hochstein surely should know this (a similar offer he made at the end of the Obama administration was rejected by Lebanon), which is why it is especially confounding that after all of his discussions with different Lebanese parties, he still ended up proposing a “unitization agreement.”

Was he lulled into thinking that Hezbollah’s uncharacteristic quiet on the maritime issue over many years offered a rare opportunity for initiating material cooperation between Lebanon and Israel? If this was his assumption, he burned a golden opportunity consecrated when Hezbollah delegated the indirect negotiations to its two allies, Parliament Speaker Nabih Berri and President Michel Aoun.

Indeed, instead of using Hezbollah’s self-removal to box it into accepting a deal seen as reasonable by the vast majority of Lebanese on legal, commercial and nationalistic grounds, rather than on imperatives related to an enduring struggle against Israel, Hochstein’s field-sharing proposal played right into Hezbollah’s hands. In fact, Hezbollah MP Mohammad Raad felt confident enough a few weeks ago, despite the country’s mounting economic problems, to deliver the party’s first fiery “redline” speech on the issue: “They tell us…it may turn out that you will need to share the gas field with the Israelis…We'd rather leave the gas buried underwater until the day comes when we can prevent the Israelis from touching a single drop of our waters.”

Hochstein’s “poison pill” deal, as some Lebanese are now calling it, also squandered a second opening the Lebanese side has offered since the fall of 2020 when the Trump administration resumed Washington’s mediation efforts.

Although it is the source of much political intrigue and enmity in Beirut, for whatever internal reasons Lebanon opened the indirect talks on the basis of a new, extended boundary claim known as “Line 29” but without officializing it as countries are legally entitled to do given relevant changes in international legal rulings. As a result, and probably for the first time in modern maritime negotiations, the Lebanese team came to the table with a well-grounded “maximalist” position (Line 29) but without having actually deposited it de jure at the United Nations.

This goodwill concession over an additional 1,430 square kilometers of sea unofficially claimed by Lebanon prevented the likely early breakdown of talks by allowing Israel and private companies like Greece’s Energen and America's Halliburton to legally move forward with exploitation activities over the last year and a half in the energy-rich Karish field, as well as its northern environs (including the southern part of the Qana Prospect). All of the former and some of the latter are outside of Lebanon’s current “minimalist” legal claim known as “Line 23.”

Of course, Lebanon’s restraint in not officializing its new “maximalist” Line 29 also gave Lebanese politicians a convenient way to accept a deal far less than what their own experts and lawyers have been saying for years should be granted to Beirut. After all, anything roughly comparable to Lebanon's current “minimalist” Line 23 could technically be spun as a victory.

Hochstein’s proposal, however, that Israel and Lebanon go into business together by sharing the Qana Prospect, decisively quashed any such maneuverability.

Should talks break down in the coming period, as now seems likely, at least two negative outcomes are almost certain. First, with the talks dead and the country sinking ever deeper into a “Deliberate Depression,” Lebanese leaders will have little to lose from officializing the “maximalist” boundary claim they are legally entitled to assert and then taking punitive action in multiple fora. This will put significant pressure on private companies operating in the (soon to be) “disputed” Karish field as well as the Qana Prospect.

Second, and perhaps most important, by offering an unworkable deal that leads to a negotiation breakdown, the U.S. and Israel will be handing Hezbollah a powerful new raison d'être as a resistance group by creating a “Maritime Shebaa,” in reference to the strategic strip of land between Lebanon, Syria and Israel that is occupied by Israel. Lebanon claims this land and considers military operations there, including by Hezbollah, as both legal and necessary in order to liberate it. The United Nations considers Shebaa to be part of Israeli-occupied Syrian land, but Syria itself supports Lebanon’s claim.

In short, a “Maritime Shebaa” will be far more evocative and unifying for more Lebanese — to Hezbollah’s distinct political benefit — than the issue of “Land Shebaa” since Lebanon’s case is much stronger in the water, just as the loss of potentially tens of billions of much-needed dollars to Israel will be daily more evident to everyone. This will likely lead to periodic military engagements in the area that negatively impact drilling and perhaps lead to deaths. At worst, this part of the Eastern Mediterranean sea could become the spark for a devastating new regional war.

Finally, at a time when Europe’s current and future gas needs have suddenly been destabilized following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, any further disruption of international supplies will only create more negative fallout. Just a few weeks ago, Israel and Energen announced that Karish had been hooked up to the national grid, with gas expected to flow in the coming months. Crucially, this extra capacity is now being seriously considered for export to the European Union via Egypt as early as September, according to Israeli and Egyptian officials. A combination of Lebanese legal actions and Hezbollah threats could substantially disrupt this schedule, however, not to mention harm Lebanon’s own hoped-for exploitation of its own blocks.

Given these dangerous consequences, the Biden administration should urgently consider whether proposing a different deal might better serve U.S., Israeli and Lebanese interests as well as regional stability. As it currently stands, there is a narrowing window for creating a stable sea boundary between Israel and Lebanon, one that must avoid, first and foremost, the “poison pill” of a shared field by trading Israel’s imminent exploitation of all of the Karish field for Lebanon’s exploitation of the Qana Prospect (which, it should be recognized, is less certain of producing hydrocarbons).

Such an arrangement would likely have to go beyond Lebanon’s current de jure Line 23 claim with a “zig-zag” around the Qana Prospect in order to be politically viable in Lebanon. This will undoubtedly be difficult for Israel to swallow since successive governments have long hoped Washington could extract for them a large chunk of the sea behind Lebanon’s current claim (as the “Hof Line” proposed a decade ago) and part of the Qana Prospect. But this compromise will also be difficult for Lebanon to accept. Beirut severely undercut its own position by officially sticking with a poorly grounded, “minimalist” boundary claim that failed to take advantage of international legal rulings over the last decade. Generations of Lebanese will have to bear some measure of loss for this.

For both sides, however, and for the U.S., all of these perceived losses should pale in comparison to the immediate and long-term benefits of finally having a stable maritime boundary between Israel and Lebanon, with the stable exploitation of valuable natural resources and the immediate strategic benefit of de-escalating — rather than inflaming — one conflict in a part of the world that simply can’t bear another.