There is a growing media narrative that the American Right's opposition to deeper U.S. involvement in the Ukrainian crisis is motivated by a latent affinity for Vladimir Putin or susceptibility to “Russian disinformation.” Despite their egregiousness and prevalence, such narratives are insufficient in explaining the Right's seemingly sudden return to non-interventionism, or, as critics say, "isolationism."

While it is true that some individuals on the right have an affinity for post-liberal politics, or view Putin through their own religious or cultural lenses, these tenuous connections do not apply to all of those on the right nor their motivations in opposing further American involvement in this crisis.

Conservatives have wavered in their support for American foreign policy due to the disproportionate sacrifices borne by Washington over 20 years of war and the widening sociopolitical chasm between American elites and the average citizen. These phenomena have inspired populists and libertarians to recover a largely dormant tradition of right-wing non-interventionism. An exploration of how that tradition was suppressed offers valuable warnings as America enters another environment of political slander intended to circumscribe the range of foreign policy debate.

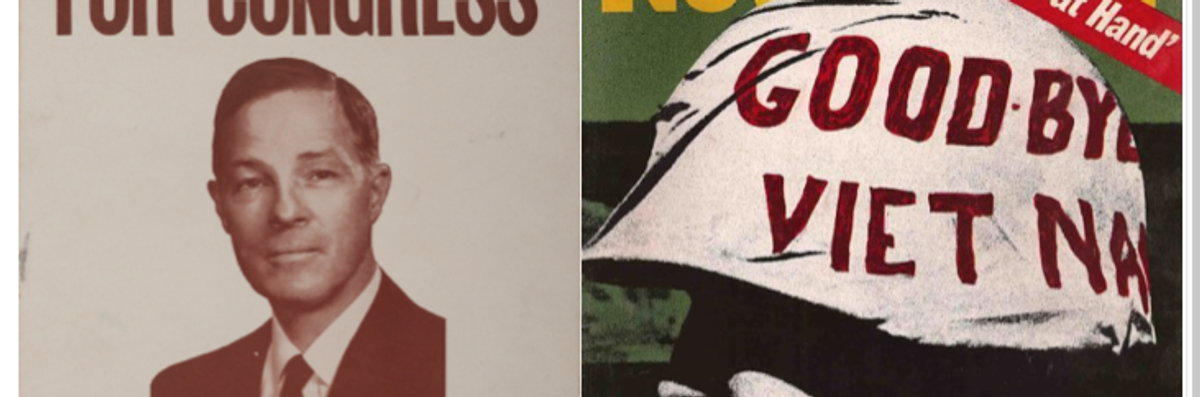

In the spring of 1968, Eugene Siler, a retired Republican congressman from Kentucky, attempted a political comeback by running for an open Senate seat. He ran on an explicitly anti-war platform and did so with the confidence that only comes with foresight. Siler was the sole member of House of Representatives, to oppose the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, reportedly calling it a "buck-passing" pretext to "seal the lips of Congress against future criticism."

Siler, in essence, was one of the last of the so-called "Old Right," a branch of conservatism that advocated a non-interventionist foreign policy. The Old Right was an assortment of fervent anti-New Dealers, trade protectionists, nativists, and non-interventionists. They were opposed to everything big: big government; big armies, big labor; big business; and big banks. These core beliefs translated into foreign policy positions that resisted entangling alliances, government-directed foreign investment, and large standing armies.

Unlike the stereotypical dove, Siler's non-interventionism was informed by a combination of traditionally conservative values. He often rationalized his non-interventionism through the lens of folksy common sense in contrast to the kind of high-mindedness that motivated his interventionist colleagues. In a statement from his office, he framed his lone dissent on the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution with an allegory of a concerned and cautious parent:"If I should send my son into the street where a fight is in progress, and if he got stung with a stone, I feel I should not then send his big brother over into the House that flung the stone. Rather I should call the son home and help him to tend to his backyard business.

Siler did not seek re-election in 1966 but decided to run for higher office two years later to return his brand of anti-war sentiment to Washington. The differences between Siler and his principal primary opponent, Marlow Cook, captured the political rifts within the GOP and the array of anti-war sentiments within American political culture at the time. Beyond their differences on domestic issues, the two men opposed the war for fundamentally different reasons. Cook initially declined to comment on Vietnam, citing the nascent Paris peace talks between Washington and Hanoi. Later in the campaign, however, he came out in opposition to the war and called for Washington to withdraw. However, his resistance was hedged by politics and partisanship. He declared that Americans could not win "a war conducted by the State Department and Executive Branch" and added that if the military wasn’t going to be "allowed" to win, "we ought to get out."

For his part, Siler assailed the war on moral, historical, and constitutional grounds. He challenged the logic of the domino theory, invoked the wisdom of the founders to beware “entangling alliances,” pointed to his early and prescient opposition to the war, and declared it "immoral and unconstitutional."

In the end, however, Cook soundly defeated Siler, who was denied any official Republican support and was outspent by Cook 13-to-one in campaign funding. Initial post-mortems of his campaign by voters and local commentators cited his age, conservatism, and "peculiar brand of isolationism" as reasons for his defeat. The very politics which inspired his opposition to the war made him unelectable even in a conservative state like Kentucky.

Cook's electoral success was characteristic of another victory — the triumph of an attenuated opposition to the Vietnam War. Despite some deeper critiques of the war present within right-wing circles, an opposition calibrated by partisanship carried the day. Such opponents attacked the war without questioning its underlying assumptions or the interventionist policies on which it was based. Vietnam would remain largely unexamined by the American political class, and the root causes of the conflict would persist, ready to reflower a generation later.

Siler's primary loss was also a coda for a more extensive ideological transformation within the Republican Party throughout the early Cold War. From 1945 to 1963, the GOP tacked significantly to the center as older conservatives, mainly from the rural Midwest, were replaced by “moderate” Republicans from elsewhere in the country and its growing suburbs. Much of this transformation was guided by party elites and media figures who desired to break with the GOP's "isolationist" past and the baggage it carried from its opposition to Washington’s entry into World War II. This transformation came at a steep cost, as it largely jettisoned from the party the vestiges of foreign policy critiques that challenged vital pillars of the Cold War.

The moderation of the GOP also cleared a path for the New Right, a more interventionist faction of right-wingers, to take the reins and steer American conservatism firmly across the Rubicon and into empire. While grassroots conservatives often viewed U.S. involvement in Vietnam with apathy, suspicion or disapproval, New Right tastemakers from the National Review and Human Events supported the war from its beginnings and viewed it as an essential component of the global struggle against Communism.

The New Right's ideas were mobilized politically through organizations like the Young Americans for Freedom (YAF), which groomed a generation of conservative leaders to believe that communism constituted "the greatest single threat" to American liberty. YAF homogenized its foreign policy identity after an open feud between its libertarian and conservative factions caused the former to walk out in protest. The institutionalization of the New Right's interventionism cemented the GOP’s transformation and aided in defining what opinions could be considered acceptable or credible in the American foreign policy debate.

The American Right has now entered another period of intense debate around the U.S. role in international affairs. Contrary to the interventionist commentariat's cynical and myopic view, the Right's opposition is not merely motivated by a self-hating "contempt for Americans," nor is it a meager exercise in "apologetics.” It is rooted in a long history of foreign policy restraint, a history now resurrected by the burdens borne on the shoulders of Americans now derided by the same commentariat now chastising them for their hesitancy about U.S. interventionism in the Ukraine crisis.

However, unlike with the intraparty fights of old, elite media retains neither a master narrative to form a unified vision for foreign policy nor a monopoly on the means to propagate it. This deadlock leaves American political culture at an impasse, one that demands compromise. If well-meaning Americans, regardless of ideology, desire a new foreign policy or solutions to our current crises, then these past intrigues should offer valuable lessons on the possible costs of "moderation." History is not linear, nor fated, nor has it ended, and it is within our power to avoid its repetition.