On March 2, the UN General Assembly, meeting in emergency session, voted 141 to 5, to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. To the surprise of many, Cuba abstained, despite its close relations with Moscow and its belief that the West instigated the crisis by expanding NATO right up to Russia’s borders, ignoring its legitimate security concerns.

This is not the first time Cuba has been caught between loyalty to its most important ally and bedrock principles of its foreign policy — non-intervention and the right of small states to sovereignty, even in the shadow of Great Power adversaries. To understand Cuba’s position on Ukraine, we need only look back at previous occasions when Cuba had to walk the same diplomatic tightrope.

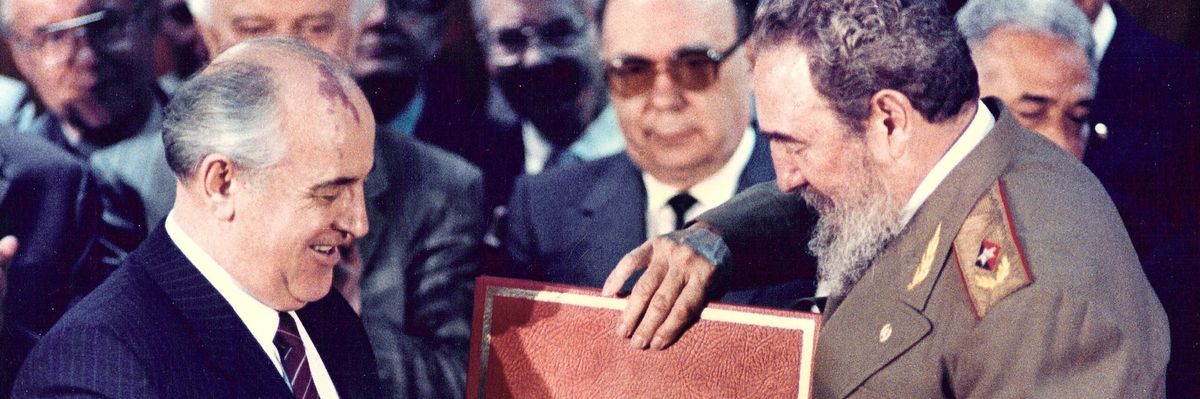

The Deep Roots of Cuba’s and Russia’s Friendship

Cuba’s friendship with Russia dates back to the 1960s, when the Soviet Union embraced the Cuban revolution, providing the arms Cubans used to defeat the U.S.-sponsored exile invasion at the Bay of Pigs, as well as the financial aid Cuba needed to survive the U.S. economic embargo. Soviet aid was “a matter of life and death in our confrontation with the United States,” Fidel Castro acknowledged. “We alone against a superpower would have perished.”

Relations with Moscow broke down after the Soviet Union collapsed, when Boris Yeltsin abruptly cut off economic assistance, plunging the island into a decade-long depression. But in 2000, President Vladimir Putin visited Havana to begin rebuilding relations. Over the next two decades, a series of trade deals deepened economic ties. Then, in 2009, Raúl Castro visited Moscow and the two countries agreed to a “strategic partnership” to include tourism, economic, scientific, and diplomatic cooperation, and renewed “technical military cooperation.” Five years later, Putin canceled 90 percent of Cuba’s $32 billion Soviet-era debt.

When President Miguel Díaz-Canel went on an extended diplomatic tour shortly after his inauguration, Moscow was his first stop. When Cuba was reeling from the impact of the coronavirus pandemic in 2021, in desperate need of humanitarian assistance, Russia sent tons of food and medical supplies. Just days before Russia launched the invasion of Ukraine, Putin dispatched Russian Deputy Prime Minister Yuri Borisov to Havana to ”deepen” bilateral ties, and Russia agreed to postpone until 2027 payments on Cuba’s new $2.3 billion debt.

Although Cuba is nowhere near as dependent on Russia today as it was dependent on the Soviet Union, Russia is once again Cuba’s principal ally among the major powers at a time when the United States has returned to a policy of hostility and regime change.

Czechoslovakia, 1968

When the Soviet Union and other Warsaw pact powers invaded Czechoslovakia on August 20, 1968, to depose the reform communist government of Alexander Dubcek, the Cuban government was silent for three days. Cubans were generally sympathetic to Dubček’s attempt to plot a course independent of Moscow because Cuba itself was in the midst of deep disagreements with the Kremlin over both foreign and domestic policy. In January, Fidel Castro had accused Moscow of delaying oil shipments as a warning about Cuba’s apostasy.

When Castro finally spoke out, people were shocked that instead of condemning the invasion of this small country by its larger neighbor, he justified it backhandedly as a “bitter necessity” to preserve socialism in Czechoslovakia and the integrity of the socialist bloc. But, he asked rhetorically, would the new Brezhnev Doctrine apply to Cuba? “Will they send the divisions of the Warsaw Pact to Cuba if the Yankee imperialists attack our country?” He knew the answer was no. Cuba was too far away, and in Washington’s sphere of influence.

The Brezhnev Doctrine’s implicit assertion of a Soviet security sphere in Eastern Europe, overriding the sovereignty and territorial integrity of other countries, posed an obvious problem for Cuba because of the doctrine’s uneasy similarity to the Monroe Doctrine. In the aftermath of Czechoslovakia, voices on the Latin American right were clamoring for Washington to invade Cuba in retaliation.

Castro reiterated the importance of the principle of non-intervention, calling it a “shield” for weaker nations against the depredations of Great Powers. He acknowledged that the Soviet invasion was “unquestionably a violation of legal principles and international norms. From a legal point of view, this cannot be justified,” he admitted. “Not the slightest trace of legality exists. Frankly, none whatever.”

The speech marked a turning point in Cuba-Soviet relations. Moscow’s gratitude for Cuba’s support eased bilateral tensions and led to deeper political and military cooperation and increased economic assistance.

Afghanistan, 1979

In September 1979, Cuba hosted the Sixth Summit of the Movement of Nonaligned Nations and began its term as chair — the culmination of Fidel Castro’s ambition to become a leader of the global south. Just three months later, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, a nonaligned member. The invasion dealt a fatal blow to Cuba’s argument that the Soviet Union was a “natural ally” of the nonaligned, tarnishing its leadership of the Movement.

The Security Council called the General Assembly into emergency session to consider a resolution condemning the invasion. Cuban ambassador Raúl Roa denounced the United States for “rolling drums of a new cold war,” but admitted that Cuba faced an “historical dilemma” because many of its friends saw the resolution as a defense of national sovereignty and peoples’ right to independence. “Cuba will always uphold that right,” Roa insisted, but Cuba would “never carry water to the mill of reaction and imperialism.” He made no effort to justify the Soviet action and said not one word in its defense. Nevertheless, Cuba voted no on the resolution, which was adopted 104 to 18.

Two days later, Fidel Castro hosted three U.S. diplomats who had come to implore him to speak out publicly against the Soviet invasion. Cuba did not support the Soviet action, Castro acknowledged. “Anything which affects the principle of non-intervention affects us, and we know it.” But whatever disagreements Cuba had with Moscow, it would not side publicly with the United States. “We have always had a friend in the Soviet Union and we have always had an enemy in the United States,” he said. “Therefore, we could not possibly align with the United States against the Soviet Union.”

Ukraine, 2022

After Russia launched its invasion of Ukraine, the Cuban government’s public statements blamed the West for creating the conditions that led to the crisis by ignoring Russia’s repeated warnings about NATO expansion. Yet despite echoing Russia’s rationale for the attack, Cuba never endorsed it. On the contrary, in the UN General Assembly debate, Cuba’s representative. Pedro Luis Pedroso Cuesta, noted Russia’s “non-observance of legal principles and international norms.”

“Cuba strongly endorses and supports those principles and norms,” he went on, “which are, particularly for small countries, an essential reference to fight hegemony, abuse of power and injustice.” He repeated Cuba’s earlier call for a negotiated solution to the conflict “that guarantees the security and sovereignty of all and addresses legitimate humanitarian concerns…. Cuba will always defend peace and unambiguously oppose the use or threat of use of force against any State.” On the resolution condemning Russian aggression, Cuba, along with 34 other countries, abstained.

Cuba as Collateral Damage

After Venezuela failed to vote on the UN resolution, senior U.S. officials traveled to Caracas to discuss with President Nicolás Maduro the possibility of lifting U.S. sanctions on Venezuelan oil sales to offset the shortage of global supply induced by the impending boycott of Soviet oil and gas. Heretofore, the Biden administration had refused to even recognize Maduro’s government. Cuba, with no oil to offer, received no such overture.

The West’s sanctions against Russia are likely to hurt Cuba, too, making it even harder for Havana to conduct international financial transactions through Russian banks, and harder for Russian tourists to get to Cuba. At the dawn of the new cold war, Cuba is once again caught in the crossfire.

Cuba no longer has any special ideological affinity for Russia and is far less dependent on it economically than it was on the Soviet Union in 1968 or 1979. But neither can Havana afford to spurn the one major power that has stood most consistently by Cuba’s side through decades of U.S. efforts at subversion. Realpolitik dictates that Cuba cultivate good relations with major powers like Russia and China so long as it lives in the shadow of a hostile United States. “Our isolation by the United States has forced us to ally with the rest of the world,” Castro told U.S. diplomats in 1979, explaining his refusal to denounce the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

So once again, Cuban diplomats are called upon to thread the needle, expressing sympathy and understanding for the indefensible actions of Cuba’s principal ally without actually endorsing them, and simultaneously trying to uphold the international principles of state sovereignty and non-intervention that their ally has violated — principles essential for the defense of Cuba’s own sovereignty. As Castro told the U.S. diplomats in 1979, “We are playing two roles...It's not easy.”