A Russian invasion of Ukraine risks disastrous military escalation between two nuclear powers, and would have immediately severe consequences for European security and the Ukrainian people.

It’s crucial to avoid this catastrophic scenario through diplomacy if possible, and to manage what could become runaway escalation if Russia does increase its aggression. But hard-liners in Washington are working to cut off flexibility for a negotiated solution or effective crisis management in Ukraine. Some of this effort is rhetorical and waged in the press, as in the firestorm of inside-the-beltway criticism that descended after President Biden made the reasonable point that U.S. responses should be proportional to Russian provocation.

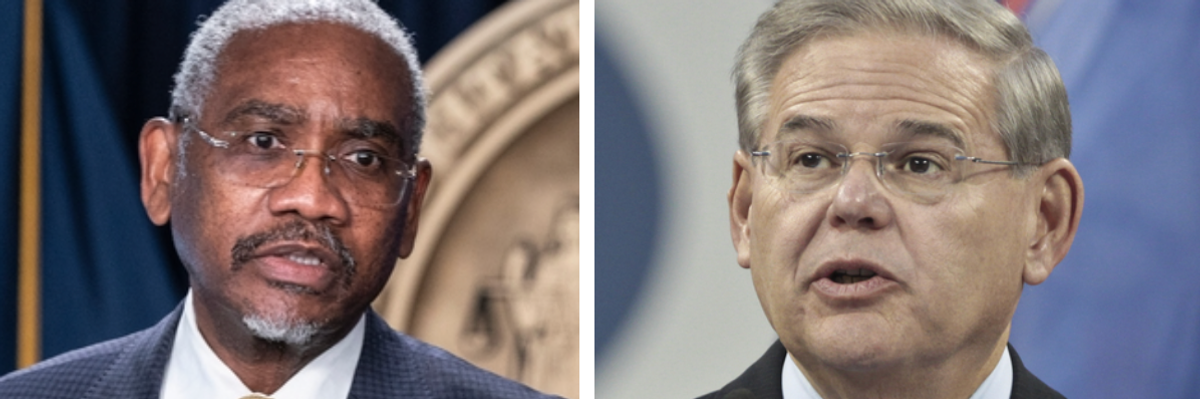

But the effort to narrow the scope for diplomacy is emerging in Congressional legislation as well. A bill advanced in the Senate by Democratic Senator Bob Menendez, the chair of the Foreign Relations Committee, and in the House by Democratic Chairman Gregory Meeks of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, would push the Biden Administration in an even more hawkish direction.The bill begins with a statement that the administration should “not cede to the demands of the Russian Federation regarding NATO membership or expansion.” Taken literally, this would remove the opportunity for negotiators to engage with Moscow’s core demands, including a ban on future NATO membership for Ukraine.

As the journalist Fred Kaplan pointed out, and few serious commenters dispute, there are a host of practical reasons why Ukraine is unlikely to join NATO for a long time, if ever. For one, it is far from meeting standards for membership. Second, NATO membership requires commitment by all members to a military alliance. Given the conflict with Russia, it’s also difficult to see alliance members making that commitment — notably, even the United States itself has not shown any willingness to commit the U.S. military to fight in Ukraine. Trying to eliminate flexibility regarding Ukrainian membership in NATO thus cuts off avenues for compromise that would involve no tangible sacrifice beyond the symbolic but could avoid war.

This up-front declaration is a "congressional finding" that lacks force of law and could technically be ignored by the administration, although a vote to affirm it could significantly narrow political space to negotiate. But other areas of the bill are legally binding. The most notable is Title 3, which lays out economic sanctions to be imposed on Russia and the triggers for those sanctions. The sanctions target Russian banks, state-owned enterprises, government debt, energy firms, and the Nordstream pipeline, as well as many individual members of the government and military. Given the size and economic significance of Russia, they are the most extensive economic sanctions the U.S. has attempted to deploy since the post-Cold War global economy took shape.

The problem is that the bill mandates that the full set of sanctions be applied in an “all or nothing” manner that is extremely difficult to reverse, and effectively on a hair trigger. This sharply narrows the ability to align them with the nature of Russian provocation, and to use the lifting of sanctions as an incentive for improvements in Russian behavior.

The bill requires the full set of sanctions to be triggered if the administration finds that “Russia is engaged in…a significant escalation of hostilities or hostile action in or against Ukraine,” and “such escalation has the aim or effect of undermining, overthrowing, or dismantling the Government of Ukraine…or interfering with the sovereignty or territorial integrity of Ukraine.”

The entire range of sanctions could thus be triggered by actions well short of a Russian invasion or occupation, as long as such actions appeared to “undermine” the government of Ukraine or in any way interfere with its sovereignty. A cyber-attack or perhaps even a propaganda broadcast to the Ukraine could be interpreted to meet the requirements for this finding.

Once these sanctions are triggered the bill makes them extremely difficult to lift. To end sanctions, the legislation requires Russia to make a formal agreement with the government of Ukraine. Ukraine would effectively be granted full veto power over whether sanctions may be lifted once imposed. Putting Ukraine in the driver’s seat would greatly reduce the U.S. ability to calibrate sanctions in response to Russian actions. Thus, once they are triggered and locked in, Russia may have little incentive to hold back from further escalation.

Some measures targeting individual Russians could also be counterproductive. The sanctions sweep in a wide range of Russian government officials and military commanders, confiscating their wealth and attempting to make them persona non grata in the global financial system. Yet these officials will be the individuals across the negotiating table or headed into a potential battlefield. Targeting these individuals will not facilitate a diplomatic solution or management of escalation should it occur.

Other areas of the bill raise concerns as well. The legislation would grant at least $500 million in foreign military assistance to Ukraine, in addition to the $200 million in new assistance sent over the last month. This makes Ukraine the third leading recipient of U.S. military assistance globally, after Israel, and Egypt. While it wouldn’t come close to giving Ukraine the ability to combat Russia on its own, it may come with U.S. military advisors that would increase the danger the U.S. would be drawn into a conflict. The bill also takes steps to directly involve countries bordering Russia in negotiations to end the crisis, which would make it much more difficult to reach an agreement.

The goal of the legislation in opposing Russian aggression in Ukraine is a worthy one. But there is no sense in this legislation of any desire to work toward an agreement based on compromise with Russian concerns. There is instead a pervasive assumption that the U.S. can simply impose its will on Russia, despite the fact that the legislation does not provide for the massive commitment of U.S. troops that would be necessary to do this. Rather than lay the groundwork for a diplomatic solution, the bill appears aimed at radically narrowing the space for diplomacy. Effective diplomacy requires finding face-saving compromises to avoid humiliating either party. The bill instead gives the sense that many in Congress want to inflict a humiliating and open defeat on Russia. Absent the willingness to fight the largest war since WWII, this is not realistic.

This year marks the 40th anniversary of the Cuban Missile Crisis, a U.S.-Russia standoff that threatened global nuclear war. Foremost among the lessons of that crisis is the importance of flexibility in achieving a peaceful solution to superpower conflict. We now know that President Kennedy’s concession in removing U.S. missiles from Turkey, a concession so controversial it was kept secret for decades, was critical to reaching a peaceful resolution of the crisis.

The Ukraine crisis is, fortunately, not yet as serious as that one. But the same kind of flexibility and diplomatic agility will be needed to manage it. By passing legislation which would significantly restrict such flexibility, Congress would move in the wrong direction, and increase the risk that the current crisis will go catastrophically wrong.