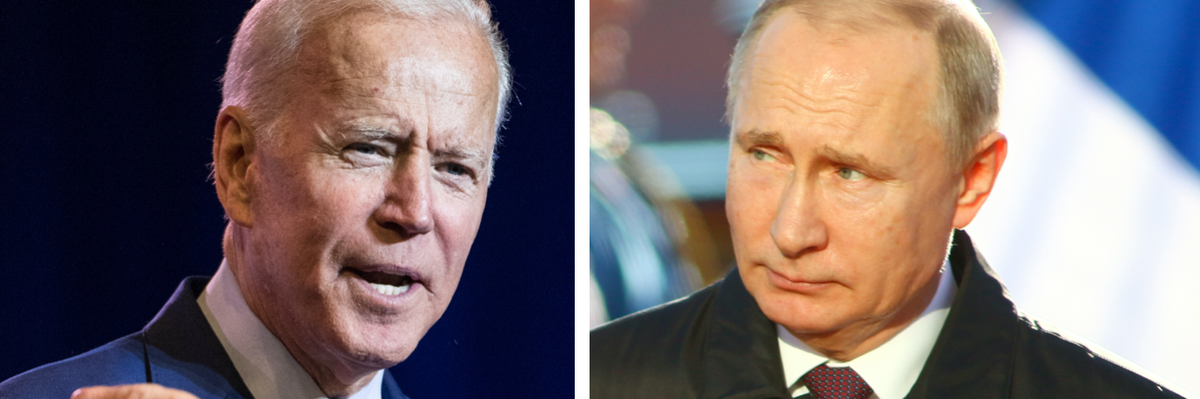

The virtual meeting between President Biden and Russian leader Vladimir Putin on December 7 didn’t resolve the crisis that began when Russian forces massed around Ukraine’s border, where they currently remain. But Biden’s readiness to engage in further talks with Russia in order to reach an unspecified “accommodation” provides an opportunity for diplomacy to avert a looming disaster.

Russia’s military build-up on Ukraine’s border has two objectives — one is to force a settlement, on its terms, between Kyiv and the Russian-backed separatists in Ukraine’s east, in line with the February 12, 2015, Minsk II Agreement. Moscow’s second but more immediate goal is to pressure NATO to meet a list of demands: a legal guarantee that it will not admit Ukraine to its ranks, essentially a renunciation of the April 3, 2008, Bucharest Summit declaration that all but promised membership; a commitment not to emplace NATO’s troops or strike weapons on Ukrainian territory; a pledge that American weapons capable of striking Russia will not be stationed in states neighboring it; and an agreement to revive the Intermediate Nuclear Forces (INF Treaty), which President Trump formally exited in August 2019. On Friday, the Russian foreign ministry presented many of these proposals in the form of a draft treaty.

Some experts suggest that Russia’s demands are so extravagant that they are designed to fail and make an invasion of Ukraine seem legitimate. But there remain reasons to believe that Russia still hopes to avoid war, is making an opening bid in a negotiation, and would settle for less than it now demands because it understands that attacking Ukraine could prove costly.

Indeed, Russian ground forces moving westward following the initial air and missile attacks could encounter dogged resistance, especially once they enter areas containing a substantial ethnic Ukrainian majority. While the military balance between states can be useful for predicting the winner, history shows that those confident of quick victory may face unforeseen complications.

The United States would impose more economic sanctions on Russia, including severing it from the SWIFT messaging system used for global banking transactions. At their virtual meeting, Putin dismissed Biden’s threat of further sanctions; Russia, he countered, had become used to them. Washington has been on a sanctions binge for the past two decades — nearly 8,000 were in place by 2019 — and Russia and other targeted countries have devised various workarounds to ease the pain. Moreover, cutting Russia off from SWIFT would hurt the EU’s trade with Russia, which totaled $219 billion in 2020, as well as its banks, which have $56 billion due back from Russian borrowers. Still, additional penalties could hurt the Russian economy, which has just begun a (still uncertain) recovery following a three percent contraction last year caused largely by the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Were sanctions so easy to cope with, countries on the receiving end wouldn’t complain continually about them.

The Nordstream II gas pipeline to Europe — already opposed by the Green Party, a member of Germany’s new coalition government — could be doomed, and Russia, whose economy relies heavily on oil and gas exports, would forgo billions of dollars in annual revenue. Europe is divided on Nordstream — some countries tout its benefits, while others warn that it exposes the continent to Russian blackmail — but Russia’s leaders see it as very beneficial to their country’s economy.

France and Germany, the two biggest proponents in Europe of engagement with Russia, would lose influence relative to Poland and other dogged opponents of rapprochement. More generally, Russia will effectively, and indefinitely, burn its bridges with the West. True, Moscow has the strategic partnership with China to fall back on, but it would have more strategic flexibility if it could combine that with a working relationship with the West, as it did in years past.

None of this means that Putin’s warning that NATO will cross Russia’s “red lines” if the alliance admits Ukraine amounts to posturing or that his national security concerns lack foundation and can be dismissed as propaganda.

A view widely-held in the United States, including by the Biden administration, is that Ukraine, an independent country, must be free to make its foreign policy choices independent of other countries’ preferences. As the September 1 “Joint Statement on U.S.-Ukraine Strategic Partnership,” put it, “Sovereign states have the right to make their own decisions and choose their own alliances.” This is true in principle, but it does not obviate the reality created by the amalgam of power and geography, namely, that if NATO grants Ukraine’s aspiration to join its ranks it will commit itself to defending a weak country that has a 1,426-mile border with Russia and that the hazards of making good on that pledge will be borne overwhelming by the United States, not its NATO allies.

Another prevalent assessment, voiced recently by influential Russia experts, is that Russia’s claims to be threatened by the prospect of Ukraine’s entry into NATO amount to a ruse — that what Putin really fears is a democratic Ukraine. Though Putin presides over an authoritarian polity, the historical record demonstrates that Russia has complained consistently about the proposals for, and the implementation of, NATO’s expansion toward its borders, including during the 1990s, when Russia, led by Boris Yeltsin, was hailed in the United States as a democracy and a partner. As Thomas Pickering, the American ambassador to Russia, wrote to Washington in a now-declassified cable in December 1994, hostility to NATO expansion “is almost universally felt across the domestic political spectrum here.” Hence Moscow’s preoccupation with NATO isn’t a Putin phenomenon.

NATO not only opened the door to Ukraine’s (and Georgia’s) membership in its Bucharest summit declaration — “We agree today that these countries will become members of NATO” — it has never closed it thereafter. Moreover, the U.S. secretaries of state and defense reaffirmed recently that Ukraine may yet join the alliance. Meanwhile, since 2015, American troops have been training Ukraine’s armed forces and the United States has been holding regular military exercises with Ukraine. Washington has also provided Kyiv with $2.5 billion of weaponry and military equipment, $400 million in this year alone, and the National Defense Authorization Act for the 2022 fiscal year approved by Congress earmarks $300 million for the Ukraine Security Assistance Initiative.

No American government would, no matter the circumstances, regard parallel developments in its own hemisphere benignly. The United States, a superpower, sees sources of insecurity in every corner of the planet and has a 200 year-old doctrine that denies the right of countries in its neighborhood to join an adversary’s military alliance or play host to its weapons (recall the Cuban Missile Crisis). How can Washington reasonably expect Russia to react differently?

Americans might reason that Russia, a nuclear power with a powerful military, surely knows that Ukraine’s admittance to the alliance is unlikely because a 30-member bloc will fail to reach agreement on a such a controversial and consequential step. But that amounts to arguing that Russian apprehension is valid only to the extent that it comports with Americans’ reasoning. Having witnessed NATO grow from 16 members in the late 1990s to 30 today, it is scarcely unreasonable for Russia’s leaders to anticipate additional expansion, including membership for Ukraine.

This current crisis remains dangerous, and the consequences of its boiling over into war would be disastrous, above all for Ukraine. But there are ways to prevent that outcome. The Biden administration’s willingness to hold follow-on negotiations with Moscow is therefore a wise move.

While Biden cannot possibly meet Putin’s demand for a legal guarantee that Ukraine will be barred from NATO, diplomats can surely negotiate to produce a formulation that provides Russia an assurance to allay its concerns that there will be no short-term change in Ukraine’s status with respect to NATO but does not foreclose Ukraine’s options.

But will Russia be satisfied with that? Ideally Moscow wants a neutral Ukraine, a la Cold-War Austria. Will it be willing to settle for something short of that? We won’t know — and perhaps even the Russians don’t — until the effort is made to find language that reconciles Ukraine’s insistence on self-determination and Russia’s demand that its security interests be respected. Given the continued danger of war, the effort is certainly worth it.

U.S. negotiations with Russia should not be confined to Ukraine alone. They should include confidence-building measures aimed at reducing the risk posed by continual close encounters between Russian and American warships and aircraft in the Black Sea and Baltic Sea.

The usual chorus of denunciation will depict any U.S. dialogue with Russia to defuse the immediate crisis as a cave-in to Putin’s pressure. Such complainants aren’t actually willing to go to war for Ukraine; they want to pretend they might and assume that Russia will be deterred in consequence, no matter that the geographical and military circumstances overwhelmingly favor it. That amounts to engaging in bravado and leaving Ukraine to deal with the consequences if the bluster fails to concentrate minds in Moscow.

The current crisis involving Ukraine may recede, but we shouldn’t count on being lucky the next time. Let the negotiations begin.