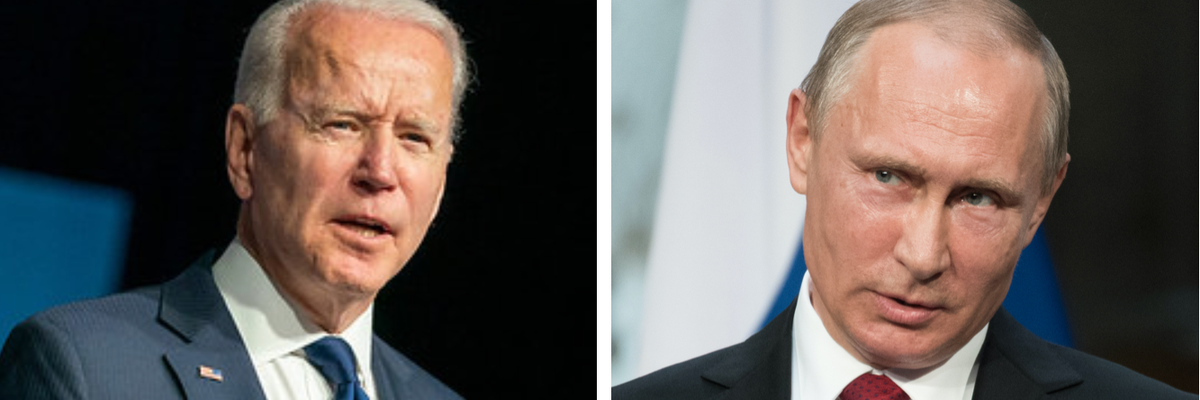

Tomorrow, December 7, Presidents Joe Biden and Vladimir Putin will meet virtually in the midst of the most intense crisis over Ukraine since Russia seized Crimea in 2014 and fostered military operations in Eastern Ukraine.

Biden’s first task is to convince Putin that further military aggression against Ukraine would be met with a serious Western military response, even though Ukraine is not a member of the Alliance and thus does not benefit from its formal military-response provisions.

It’s still hard to believe that Putin would be so reckless, since such actions would lead to direct military conflict between Russia and, most important, the United States. But miscalculations and accidents can happen.

Putin likely has several motives, even-in-crisis-short-of-war. They include reinforcing his domestic political control by hyping an external “threat,” claiming that Russia is again a great power, demanding greater respect from the West, gaining acceptance of Ukraine as a neutral “buffer” state in Central Europe, or even embarking on a general campaign of destabilization in Central Europe and disarray in NATO. (On the last, at least for now, Putin has brought the allies together.)

What should be agreed on Ukraine

Whatever Putin’s motives, the requirement now is to keep the crisis from escalating into open conflict. And NATO’s U.S.-led military preparations will likely suffice to deter any Russian military adventurism.

But the virtual summit can and should be about much more than just reducing tensions and calming fears. Practical steps should include:

— Mutual commitment to work toward resolving, not just containing, the crisis over Ukraine. That can extend to Eastern Ukraine. But gaining Russian concessions on Crimea is beyond Biden’s reach: Putin would be inflexible. Thus the two leaders should just “reserve their positions” in order to avoid injecting an unsolvable element into tension-reduction efforts.

—Major reduction of Russian forces near the Ukrainian frontier, along with moderation of NATO military activities in Ukraine, plus agreement to refrain from future provocative acts.

— Exchange of Russian and NATO military observers — or observers from the UN or the Organization for Security and Cooperation — on the two sides of the Ukraine-Russia border, plus the lines of demarcation in contested areas in Ukraine.

— Revival and intensification of the Minsk II Process, designed in 2014 to try resolving the Donbas crisis, but long since moribund. The three co-chairs are Russia, Ukraine, and the OSCE, with France and Germany as mediators. Biden should offer U.S. participation, and Putin should accept it.

Limits on Biden

As Biden presses Putin on Ukraine, he has to bear in mind limitations on his approach, resulting in part from some U.S. and NATO policies. In talking with Putin, Biden has to avoid topics that would contravene formal NATO provisions, reiterated by Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg at the end of last week’s foreign ministers’ meeting in Riga, Latvia: “Ministers made clear that we stand by our decisions.” That was code for three NATO positions: 1) No outside country can influence NATO decisions (as on enlargement); 2) any country in the OSCE has the right to choose its own alliance; and 3) Ukraine and Georgia “will join NATO.”

The first, a NATO “principle” since the 1990s, was originally adopted to reassure Central European states that the Alliance would reject any Russian effort to interfere with NATO decisions affecting them. The second was NATO’s so-called “open door,” which in theory means that any country belonging to the OSCE (including Ukraine and Russia!) could choose to join the Alliance. And the third commitment, that Ukraine and Georgia will become NATO members, was adopted at NATO’s 2008 summit in Bucharest and repeated many times since.

But the third commitment is a red flag to Russia, given anxiety – real or just exploited by Putin— that NATO seeks to “surround Russia.” It’s a nonsensical commitment, however, since it will never happen: joining NATO requires unanimous consent and all allies’ willingness, at least in theory, to regard aggression as requiring a military response. Few allies would agree to that commitment regarding Ukraine as a formal NATO commitment (as opposed to an ad hoc response), and none with Georgia. At some point, Biden will need to get NATO to modify that position while rejecting the Russian idea that Ukraine should be a buffer state, de jure if not de facto, but that must not even be discussed with Putin.

Notably, however, Stoltenberg didn’t mention possible military action as part of the NATO deterrent to Russia: “Ministers made clear any future Russian aggression would come at a high price and have serious political and economic consequences for Russia.” U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken has said much the same. Designed to be crisis-calming, leaving out the military option does reduce the deterrent effect on Russia. After all, how much do “serious political and economic consequences” weigh in the balance against strategic interests? Most likely, however, Putin will not be emboldened by this U.S. and NATO reticence, since a Russian military attack would clearly mean war with the West.

A broader Biden-Putin agenda

Biden and Putin also need to address a broader agenda if they are to meet their mutual responsibilities as major powers. The general rubric should be agreement to avoid stress and tensions, keep competition within bounds, and build on common interests of which there are many examples — arms control, terrorism, COVID-19, and climate change, plus ongoing cooperation in the Arctic and the International Space Station.

Regarding Europe, Biden and Putin should agree on recognition of all European countries’ legitimate security, political, and economic interests. That means reiteration of OSCE principles from the 1975 Helsinki Final Act, to which both Washington and Moscow are signatories.

Further, in their virtual summit the two leaders should agree to the following:

— Immediate return of diplomatic personnel to Washington and Moscow (plus consulates), which have been reduced in tit-for-tat Cold-War fashion.

— Renewal of arms control negotiations on a wide range of issues, including initiation of talks to limit the military use of outer space, with invitations extended to other relevant parties, notably China.

— Cooperation on other regional issues (including ongoing consultations on Iran and the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action.)

— Agreement on regular U.S.-Russian strategic dialogue at the level of defense ministers and chiefs of defense (and deputies), with continuous contacts and a Hot Line II.

— Continual regular contact between foreign ministers, with a new bilateral joint consultative committee.

— Revival of the NATO-Russia Council in Brussels, currently suspended, including focus on the 19 areas of cooperation set forth in the May 1997 NATO-Russia Founding Act.

This agenda is more ambitious than can be achieved in one virtual meeting. But pursuing it could in time produce necessary understandings about the future of U.S.-Russia relations, security in Europe, and recognition that Russia will in fact be a major power — but with responsibilities as well as rights. As with all major agreements, especially at summits, most hard work has to be done in advance at lower diplomatic levels. But Biden can “kick-start” the process with Putin and see whether the Russian leader will respond.