Last week’s announcement that China supports an end-of-war declaration is a major step forward in the Korea peace process. A similar statement by the United States would give credence to President Biden’s pledge for a “calibrated” policy on North Korea while also advancing the U.S. interest in a more stable Korean Peninsula.

Indeed, the Biden administration appears sincere in its offer to talk to North Koreans without preconditions. It also has not shut debate around ending the Korean War — a move that would enjoy support from dozens of members of Congress, anti-war groups, humanitarian organizations, families awaiting recovery of American prisoners of war and missing in action service members (POW/MIA) from the Korean War, among others.

To get there, the Biden administration must confront several key questions and dynamics that could derail a serious peace process. Successfully navigating these issues could transform U.S. foriegn policy in the Koreas from one based on primacy to multilateralism.

Alliance Issues

One of the most complicated questions surrounding the formal end to the Korean War is what that will mean for U.S. defense of its ally South Korea. Analysis of the United Nations Command (UNC), the core vehicle for implementing the Armistice Agreement, is critical for understanding the security environment once a formal peace treaty is signed — a process that could be initiated through a political statement such as an end-of-war declaration.

The legal grounds under which the UNC can remain in South Korea would cease to exist post-peace treaty, since its purpose as laid out in UN Security Council resolutions S/1501 and S/1511 was primarily to repel any North Korean attack against the South. To avoid misunderstanding, Washington and Seoul should discuss in concrete terms what ending the Korean War would mean for mutual defense and long-term security interests in East Asia outside of the UNC. Such consultation should take place before any peace declaration, if they have not already taken place, and explained to the American public.

Us vs. Them Mentality

Critics of the Korea peace process say that improving bilateral relations is akin to rewarding “bad behavior.” This type of thinking assumes that North Korea will be forever hostile, locking the U.S. into a policy of maximum pressure and non-engagement. Such a moralistic lens absolves any U.S. complicity in the past breakdown in talks, such as Washington’s failure to meet its commitments in the 1994 Agreed Framework, or the Treasury Department’s designation of Banco Delta Asia in Macao as a financial institution of primary money laundering concern the same week that the Six Party’s Joint Statement was released.

Of course North Korea also bears responsibility for failures of past agreements and for framing U.S. interests in ways that perpetuate a siege mentality. A better way forward would be for both sides to recognize each other’s legitimate interests — North Korea’s desire for security, and U.S. desire for stability and nonproliferation — and focus on achieving tangible, sustainable progress in a step-by-step manner that becomes progressively larger and more consequential.

Rising Anti-China Sentiments

The growing intensity of anti-Chinese sentiments in Washington poses a major threat to the Biden administration’s ability to address the North Korea issue. As a former Chinese official noted in a track II meeting, “to China, the U.S. is trying to deprive China of its space in the international system,” which could reduce Beijing’s desire to work with the United States on the North Korea issue.

Part of the problem is that North Korea and China are regularly lumped together as threats that justify an ever-increasingly militarized U.S. foreign policy. For example, the 2021 Global Posture Review emphasizes the threat of North Korea and China as the main impetus for the U.S. military to increase its presence in the region. Hardliners in Congress also make it difficult to pursue cooperation with Beijing on issues of common interest such as North Korea.

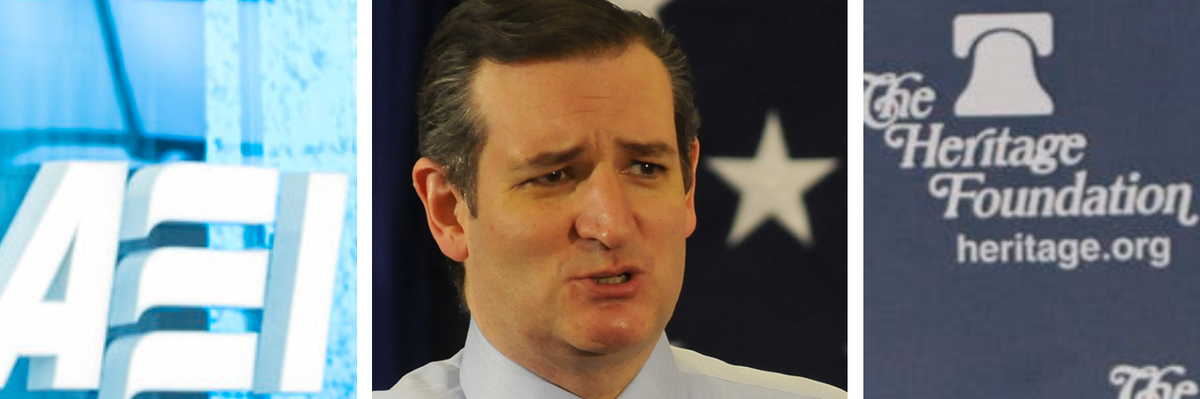

For instance, Senator Ted Cruz’s (R-Texas) description of President Biden’s China policy as “appeasement” and labeling of the Democratic Party as “structurally pro-China” reduces room for creativity and risk-taking that are necessary for the Biden administration to tackle the North Korea issue. This tendency is common among Democrats as well, including nominees for ambassadorships to Asia, who reinforce the narrative that China is a country to be defeated rather than a country to work with.

Defense Industry-Funded Opposition

Following reporting that the U.S. and South Korea were close to agreeing on the text of an end-of-war declaration (a claim that is unverified by U.S. sources), there has been a flurry of articles by scholars at U.S. think tanks about the folly of pursuing peace with North Korea.

One expert at Heritage Foundation described an end-of-war declaration as an “empty promise.” Another expert at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) described it as lacking in “seriousness about genuine security threats.” What is left unsaid is how enmeshed some of the think tanks that advance U.S. military intervention are with the defense industry. For example, the Heritage Foundation received at least $5.8 million from the Hanwha Group between 2007 and 2015. Hanwha is a South Korean conglomerate that produces autonomous weapons systems, including SGR-A1 that is designed to replace human guards on the demilitarized zone.

It is important to note that not all analysts at traditionally interventionist think tanks advocate for militaristic ideas. For example, Kori Schake of AEI recently spoke favorably of an arms control agreement with North Korea over pursuing unrealistic goals like invading the country to forcibly remove all of its nuclear weapons. The exchange of views by scholars who represent alternative perspectives should be encouraged, especially when they advance less escalatory, more diplomacy-centered solutions.

Perhaps the biggest unknown is how North Koreans will respond to U.S. support for ending the Korean War. In an ideal scenario, it would be met favorably, and lead to a broad agreement to return to the negotiating table. In the worst case scenario, Biden would be rebuffed, providing ammunition to those who are skeptical of diplomatic engagement with North Korea. If Beijing can help clarify Pyongyang’s position on the issue of ending the war and/or help those in Washington who are seeking dialogue with North Korean officials, that would help close the information gap, which in turn will give Americans more confidence to pursue diplomacy with North Korea. In the meantime, those who watch this issue should be clear-eyed in terms of the financial interests driving certain commentaries toward a deterrence-only, confrontation-based policy on North Korea.

President Biden’s instincts on foreign policy have been hawkish on certain issues like China but peace-oriented on others, as seen by his decision to end the Afghanistan War. All those who support finally ending the Korean War, seven decades after it began, should help the Biden administration overcome these analytical and political hurdles through balanced analysis and encouragement.