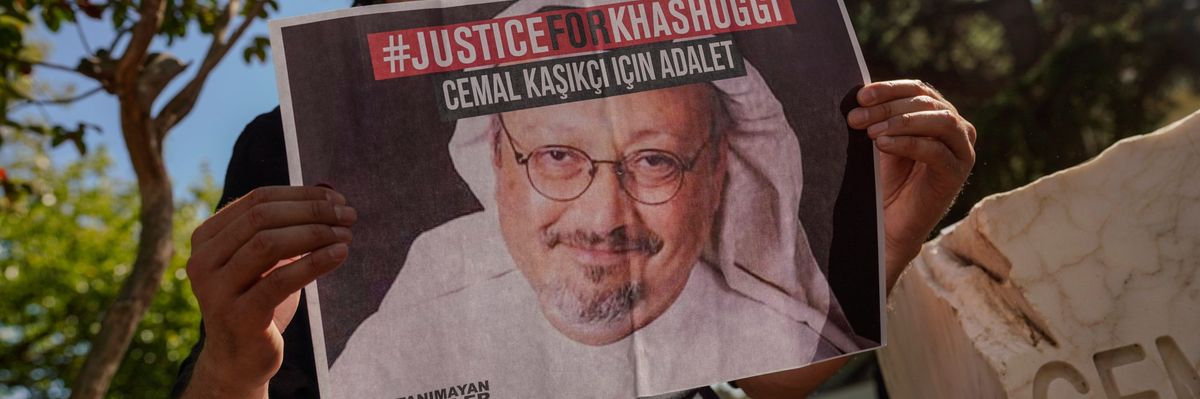

A consortium led by the Public Investment Fund of Saudi Arabia has acquired ownership of Newcastle United in the English Premier League after an 18-month long controversy over whether the Saudi state, rather than its sovereign wealth fund, would exercise control over the soccer club. Almost three years to the day after Jamal Khashoggi walked into the Saudi Consulate in Istanbul and never came out, the scenes of jubilation involving up to 15,000 Newcastle supporters celebrating the takeover vividly illustrated some of the soft power benefits the Saudi leadership anticipates will accrue from the purchase.

One of the oldest and historically more successful teams in England, Newcastle United has developed a reputation for having one of the most passionate fanbases in the country. In recent years, supporters had turned on the previous owners, accusing them of under-investing in the team and of presiding over years of poor performances.

Against this background of chronic underachievement, the April 2020 announcement that the Public Investment Fund was partnering with RB Sports & Media and PCP Capital Partners to purchase the team sparked the excitement of Newcastle fans who anticipated the deal would catapult the team into a European powerhouse just as Abu Dhabi’s takeover of Manchester City in 2008 and Qatar’s purchase of Paris Saint-Germain in 2010 did.

Although the decision to proceed with the Newcastle takeover, which had been stalled since July 2020, was framed by assurances the English Premier League received from the Public Investment Fund regarding its separation from the Saudi state, the key to unlocking the deadlock appears to have been a Saudi decision to unblock the Qatar-owned beIN Sports from broadcasting in the Kingdom.

beIN holds the Middle East North Africa rights to show English Premier League games, as well as a host of other sporting competitions, but its signal had been blocked in Saudi Arabia since 2017 as part of the blockade of Qatar. The Saudi authorities were also accused of turning a blind eye, at best, to an audacious shadow company, tellingly named beOutQ, that systematically pirated beIN broadcasting rights, including for Premier League games, in 2018 and 2019, in an apparent effort to score points against Doha during the blockade.

The fact that the Newcastle takeover was finally given the green light by the English Premier League a day after the resolution of the beIN issue was announced is unlikely a coincidence. The unpalatable truth is that business and commercial considerations were paramount over issues such as the Public Investment Fund’s apparent ownership of the planes that transported Khashoggi’s killers to Istanbul in 2018.

The enthusiasm that has greeted the new Saudi owners in Newcastle is another signal that the post-Khashoggi cold-shouldering of Mohammed bin Salman has come to an end, just as Joe Biden did not follow through on a campaign statement that he would make Saudi Arabia “the pariah that they are.”

What do the Saudis get from purchasing a team that currently lies second-last in the Premier League and without a championship since 1927? The 20 teams in the English Premier League collectively lost almost a £1 billion in the pandemic-hit 2019-20 season, and Abu Dhabi-owned Manchester City has recorded yearly losses upwards of £100 million. Buying a team hardly guarantees a conventional return on investment. It is likely the Saudis see themselves as buying a prestige asset for state-branding (or “sports-washing”) purposes because the acquisition does not contribute to the Public Investment Fund’s mission to assist in economic diversification and job creation in Saudi Arabia. There is, instead, an intangible factor that the new owners will be seeking which is about soft power projection, changing the image of Saudi Arabia, and utilizing the mass appeal of soccer to reach new audiences around the world.

Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, who doubles as the Chairman of the Board of Governors of the Public Investment Fund, has staked his credibility as the ruler-in-waiting of Saudi Arabia on Vision 2030 and the premise that he, and he alone, can transform the Saudi economy and society. Sport, entertainment, and tourism feature heavily in Vision 2030 and in the associated “giga-projects” announced by MBS since 2017 (and entrusted to the Public Investment Fund for delivery).

These include Qiddiya, a large-scale entertainment, sports, and cultural complex near Riyadh that was launched by the Crown Prince in 2017. Under Mohammed bin Salman, Saudi Arabia has also become far more active in trying to harness the power of culture and sport to burnish its image, with the first Saudi Arabia Grand Prix set to take place on a street circuit in Jeddah in December and the Kingdom is leading a push to hold the FIFA World Cup every two years, instead of four, with hopes that it might host the tournament as well.

To be sure, sports-washing is neither a new concept nor associated with Saudi Arabia alone; one need only recollect the spectacle of the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin to appreciate the convening power of elite-level sport. English Premier League games are viewed in more than 200 countries and territories and Newcastle could play a visible role in “selling” Saudi Arabia to a genuinely global constituency.

Mohammed bin Salman may therefore be hoping that the passage of time may dim the memory of Khashoggi’s murder and dismemberment, to say nothing of the Saudi war on and blockade of Yemen, and that turning Saudi Arabia into an international sporting powerhouse “normalizes” the Kingdom and its leadership after a difficult couple of years.